The seduction of power, both individual and institutional, is a tale as old as time. Within the church, the misuse and abuse of authority has taken a devastating toll in broken lives and congregations. Yet the true nature of power often goes unacknowledged and unexplored. In Redeeming Power: Understanding Authority and Abuse in the Church, psychologist Diane Langberg brings several decades of experience counseling clergy leaders and trauma survivors to this topic. Tim Hein, a pastor and lecturer in Australia and the author of Understanding Sexual Abuse: A Guide for Ministry Leaders and Survivors, spoke with Langberg about why pastors and ministry leaders sometimes feed on their flocks.

The word power is a contested one in our culture. How do you define it?

Basically, power is influence—the capacity to produce an effect. If I walk up to you, and I’m bigger than you, and I push you down, then I have done something that had an effect. And everybody has some sort of influence—even an infant. If you bring a baby home from the hospital and it starts screaming at 3 a.m., what do you do? You get up!

This is part of what it means to be God’s image-bearers. He has told us, Rule! Rule over the earth. That’s a power word. As sinners, of course, we’ve ruined this like we’ve ruined everything else. But exercising power is still part of our essence, even if individuals and systems are prone to misusing it.

If all of us wield power and influence of some sort, then why are Christian leaders, in your view, especially susceptible to becoming power-abusers? What do they fail to appreciate about the power they have?

By and large, the schools we have for educating Christian leaders do not teach about such things. Seminaries give practical knowledge about how to run a church or a ministry, but they aren’t doing enough to illuminate the nature of power and the dynamics that cause issues of abuse to arise—and then be covered up.

Another problem is that seminaries haven’t always done enough to teach leaders the importance of understanding themselves and their own vulnerabilities—the hurts and wounds that might never have been named, let alone dealt with. I’ve worked with tons of pastors over the years, and many of these good men and women go into these positions having never asked these questions of themselves. Think, for instance, of a man in the pulpit whose father physically abused him and spoke to him like he was trash. He’ll be full of wounds, and that’s going to affect how he uses his position of leadership. But his ignorance of himself and the wounds he’s carrying make him vulnerable to feeding off his sheep. I can’t tell you how many pastors have sat in my office weeping, saying, “I don’t know how I got here” after they’ve behaved abusively themselves.

A pastor reading this might be thinking, “I don’t feel very powerful. I’ve got my elders on my back, budgetary pressure to handle, and church members criticizing my sermons. Are you telling me I have dangerous levels of power?”

It doesn’t matter what you do for a living. Power is inherent in being human. For pastors, you might have power in your home, over your spouse or children. You might have power in every conversation you have, because your words have an impact on the people listening. And if you’re not aware of the power you exercise, you aren’t as likely to examine how you’re using it.

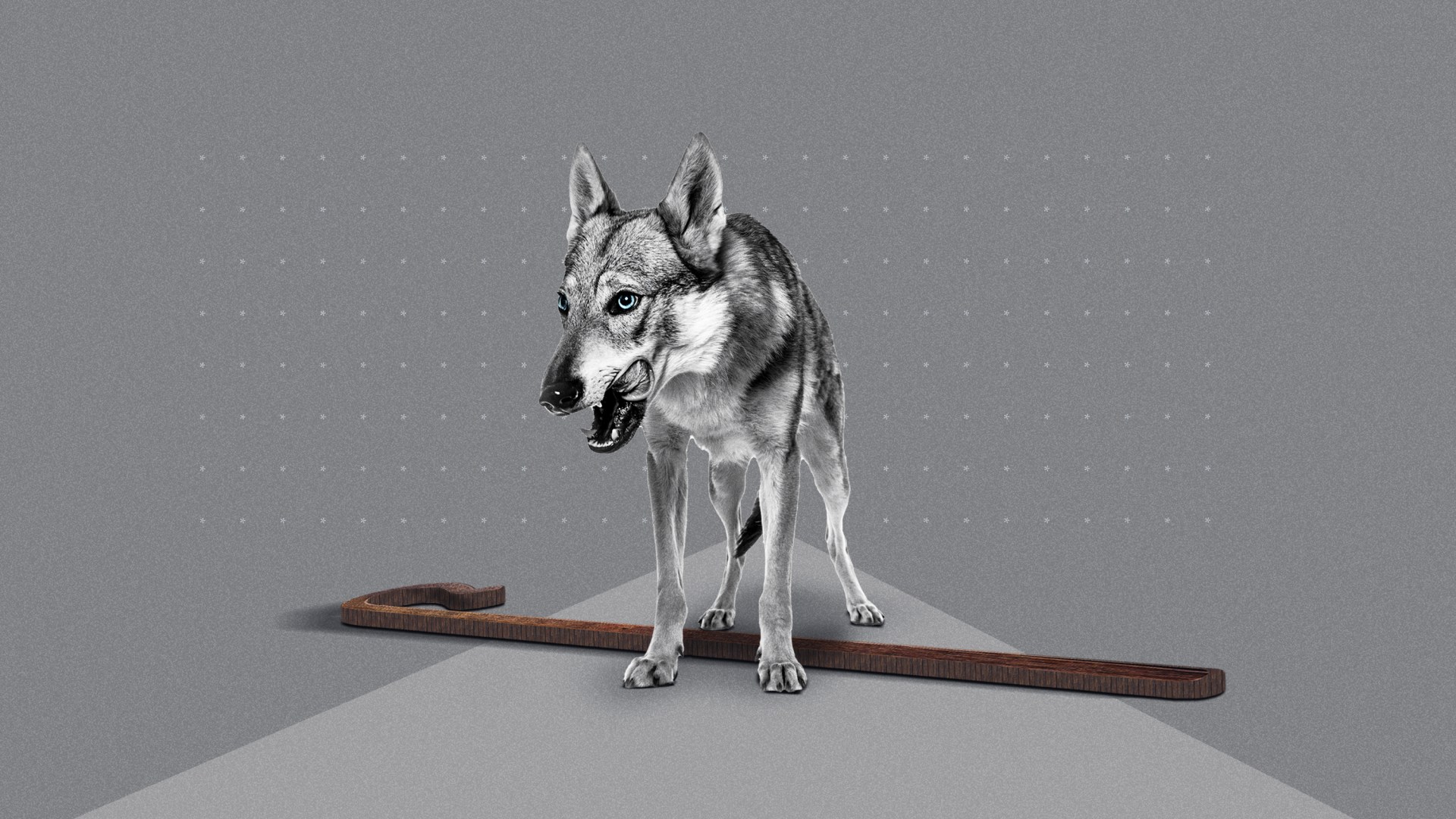

So you end up feeding off people, using them to meet your needs or make up for your vulnerabilities. Maybe that looks like going to the grocery store and being hideously rude to the cashier. Or maybe it looks like schmoozing with everybody there and knowing it will feed your ego because they’ll all think you’re wonderful. As long as you’re using the sheep for food, then you’re a wolf, not a shepherd. Ezekiel 34 warns against shepherds who feed and clothe themselves rather than their sheep. And Jesus speaks about the Pharisees in similar ways in John 10.

How do you see the broader Christian culture in the West, with its temptations toward fame and status, feeding into the problem of abusive church leaders?

Well, that’s just human nature. Think back to the beginning of creation: The one who deceived us away from God wanted to be like the Most High. Talk about an abuse of power! So it’s always there, as part of human nature, to want glory and esteem. On one level, we’re meant for those things, but after the Fall we seek them in illicit ways. Sex is one obvious way. But in subtler ways, we can find glory and esteem in externals—things like positive feedback on social media, the numbers in the pews, or the number of books you’ve sold. And it’s little things, too: You can be a pastor in a tiny town and take pride in feeling like the most important guy there.

We all want to be loved, and in fact it’s God’s design that we’re meant to be loved. So it gets muddy, because I wouldn’t ever want to say that anyone who seeks esteem is guaranteed to abuse power and have no empathy. But we need to be aware of how the Fall has corrupted that desire and made us practiced in the art of self-deception.

You say your experience as a psychologist has taught you that you can tell what is most important to someone by what that person protects most defiantly. How does this dynamic play out in the ranks of church leadership?

With most people, you can identify the one thing that refuses examination by others, the one thing you won’t let into the light. And if someone figures it out, you’ll look for other ways to hide it. One obvious concrete example is pornography. But we also do this with things like money and status.

And systems as a whole tend to do this as well. The feeling might be, “We’re this well-known church, and this terrible thing has happened, and we have to protect our reputation rather than drag this stuff into the light and let God do his work.” With churches or other institutions, what’s most important is what gets protected, and often enough that’s the institution itself.

How, then, can the church as an institutional system be redeemed from this tendency, and how can the congregation itself support this?

The way the Bible depicts the church, Christ is the head and we’re part of his body. So there’s a system involved, but it’s a system that’s supposed to follow its head. My father was sick for many years. He was a colonel in the Air Force, bright, and a fabulous athlete. But he ended up with a neurological disease. One of the lessons I learned as I watched him basically disintegrate over 30 years is that a body that doesn’t follow its head is a sick body. It’s a sick system. The church’s problem, then, isn’t that it’s a system, but that the system often fails to follow its head.

And surely, the congregation has some responsibility for keeping the system healthy, mainly by worshiping Christ and him alone. But the church also needs to pray for its leaders, that God will uphold them in godly leadership—not for the sake of gaining the material and reputational blessings we’ve come to love so much, but for God himself to be honored above all.