In this series

In his four decades as a minister, R. B. Holmes Jr. has never dealt with so much death.

More than 24,000 Floridians have died from COVID-19, including more than a few of the flock that Holmes shepherds at Bethel Missionary Baptist Church in Tallahassee.

“No one is immune from this,” Holmes told CT. “The thief is winning. The virus is a thief.”

The black pastor is especially concerned that the coronavirus has disproportionately impacted his community and other communities of racial minorities around the state. According to statistics from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, black people are 1.4 times more likely to become infected with COVID-19 and 2.8 times more likely to die from it than white people.

There are a number of possible reasons for this. The National Urban League points out that many minorities are more exposed to the virus because they work in fields that don't accommodate working from home. African Americans also tend to have more preexisting conditions—often poverty related—that put them at risk of COVID-19. On top of that, they are less likely to have health insurance.

Whatever the reason, Holmes said the crisis has created an emergency for black people, and African American community leaders, especially pastors, have to find a way to respond. After one too many funerals in 2020, he felt compelled to action.

“Why sit here as leaders and watch our people die and our families die?”

So Holmes organized the Statewide Coronavirus Vaccination Community Education and Engagement Task Force.

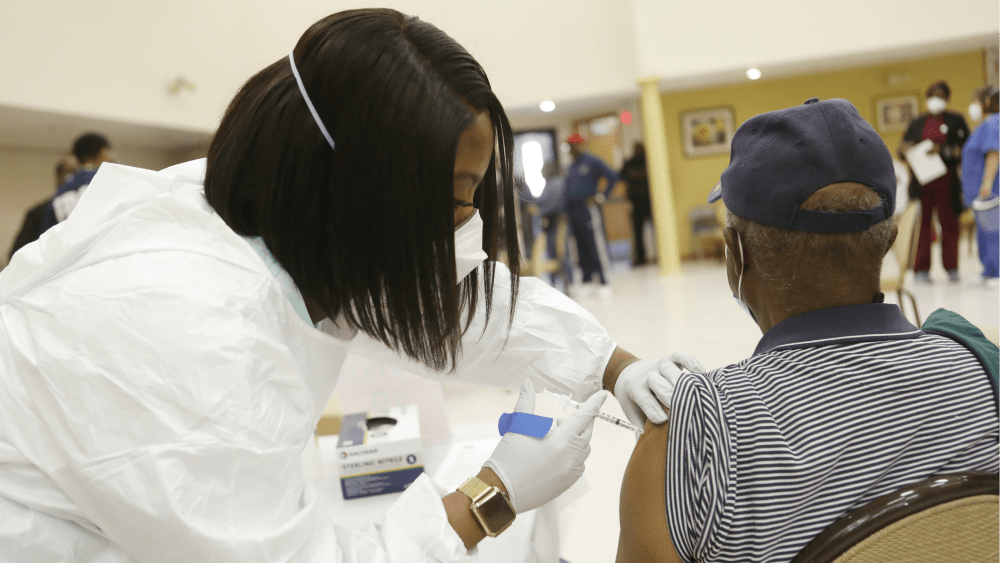

The group is partnering with hospitals and the state to better distribute vaccines—as they become available—through local churches to the people who are most at risk. On January 10, Governor Ron DeSantis announced that seven predominantly black churches would each be getting 500 doses of the vaccine to distribute to people over the age of 65. The state hopes to soon expand the program quickly, distributing vaccines to about 50 churches across Florida.

Holmes said the task force has made it their mission to locate 40 primarily black churches, community centers, and colleges to be involved with distributing the vaccine by January 31. He hopes Florida’s plan is replicated throughout the country and wants the task force to become a model for how to reach the black community.

“Our plan is very systemic, very measurable, very achievable,” he said.

There are practical reasons to involve black churches in vaccine distribution—they have buildings and parking lots and good locations for distribution. But the reasons go deeper too.

“The church is in some ways a center, not just a religious center, but a social institution as well,” said Jamil Drake, a religious studies professor at Florida State University who specializes in African American religious culture. “The church has historically been a site that the state has used to gain the trust of African Americans given the role that churches play in African American communities.”

Black communities often distrust the government and are skeptical of medical authorities. Drake said there are good historical reasons for this, citing the racist writings of 19th-century medical doctors who used science to justify slavery and 20th-century medical experiments performed on unsuspecting African Americans.

The most notorious, Drake said, was the Tuskegee Syphilis Experiment, which continued into the 1970s. The United States Public Health Service promised health care to 600 black people in Alabama in exchange for participation in a study. The health service identified 399 of the men who had latent syphilis but did nothing to help them. Instead, the service chose to study what would happen if they did nothing to treat the illness. The experiment continued for 40 years, and 128 of the participants died.

“You can’t talk about medicine and science without the history of race,” said Drake. “History is not just an antique that we observe. History is in us.”

Today, black people are less likely to seek medical treatment than white people or even get flu vaccines. There is some concern that, even though the coronavirus is disproportionately hurting black people and other minorities, black people and other minorities won’t seek out vaccines.

Anthony Evans, pastor and founder of the National Black Church Initiative, points out that administering the vaccine in black communities requires trust building. His network has decided to wait to promote the vaccine until more data confirms it is safe.

Elaine Ecklund, professor of sociology at Rice University, said that kind of caution is justified.

“People have good reason to be suspicious,” Ecklund said. “I think that’s really important to understand.”

At the same time, COVID-19 is devastating communities, and multiple controlled studies show the vaccine is safe. Competing pharmaceutical companies have come up with very similar approaches to fighting the coronavirus, and their tests have come back with consistent results.

“The science is pretty clear at this point that our very best hope is getting as large a group as possible vaccinated,” Ecklund said. “That’s all we have now.”

Ecklund, who is director of the Religion and Public Life Program at Rice University, believes that churches helping distribute vaccines could be a good first step toward the larger goal of building trust. Church leaders should take the opportunity to help Christians understand science and see how it is compatible with faith.

Religious leaders can also help health authorities think through the ethical questions involved with distributing limited resources. Morally, Ecklund said Christians have a legitimate role to play in these fields and can use their influence to address injustices and “care for the least of these.”

Janice Minnis, an administrative assistant at the Koinonia Worship Center and Village in Pembroke Park, said to her it only makes sense that the church should help at a time like this. The center is one of the Florida churches that has signed on to help distribute the vaccine, and on January 10, they facilitated 500 people receiving their first COVID-19 vaccine shot.

“The church gives hope through our Lord and Savior Jesus Christ,” she said. “We ought to be a beacon of light in our community as well.”

According to Minnis, organizing the event wasn’t much different than other events at the church. From her perspective, the church can respond to the coronavirus in the same way it might to a hurricane on the Florida coast.

“This is something that we do on a regular basis when it comes to emergency situations,” she said. “The church should be a safe haven, and what better place to get the help you need than from the church?”