Churches weren’t always ready to help Evelyn Mangham. When she cold-called them in 1975 seeking sponsors for refugees from the Vietnam War, they often had other plans and other financial commitments.

But in call after call with Christian and Missionary Alliance (CMA) churches, and then any congregation affiliated with the National Association of Evangelicals (NAE), Mangham pushed, quoted Scripture, told stories about Vietnamese people from her 20 years as a missionary, and applied moral pressure.

One pastor told Mangham his congregation couldn’t help because they were in the middle of a building project—working on a new parking lot. She sputtered, “But these are people.”

By the end of the year, she had convinced evangelical churches to sponsor 10,000 refugees from Vietnam, Laos, and Cambodia.

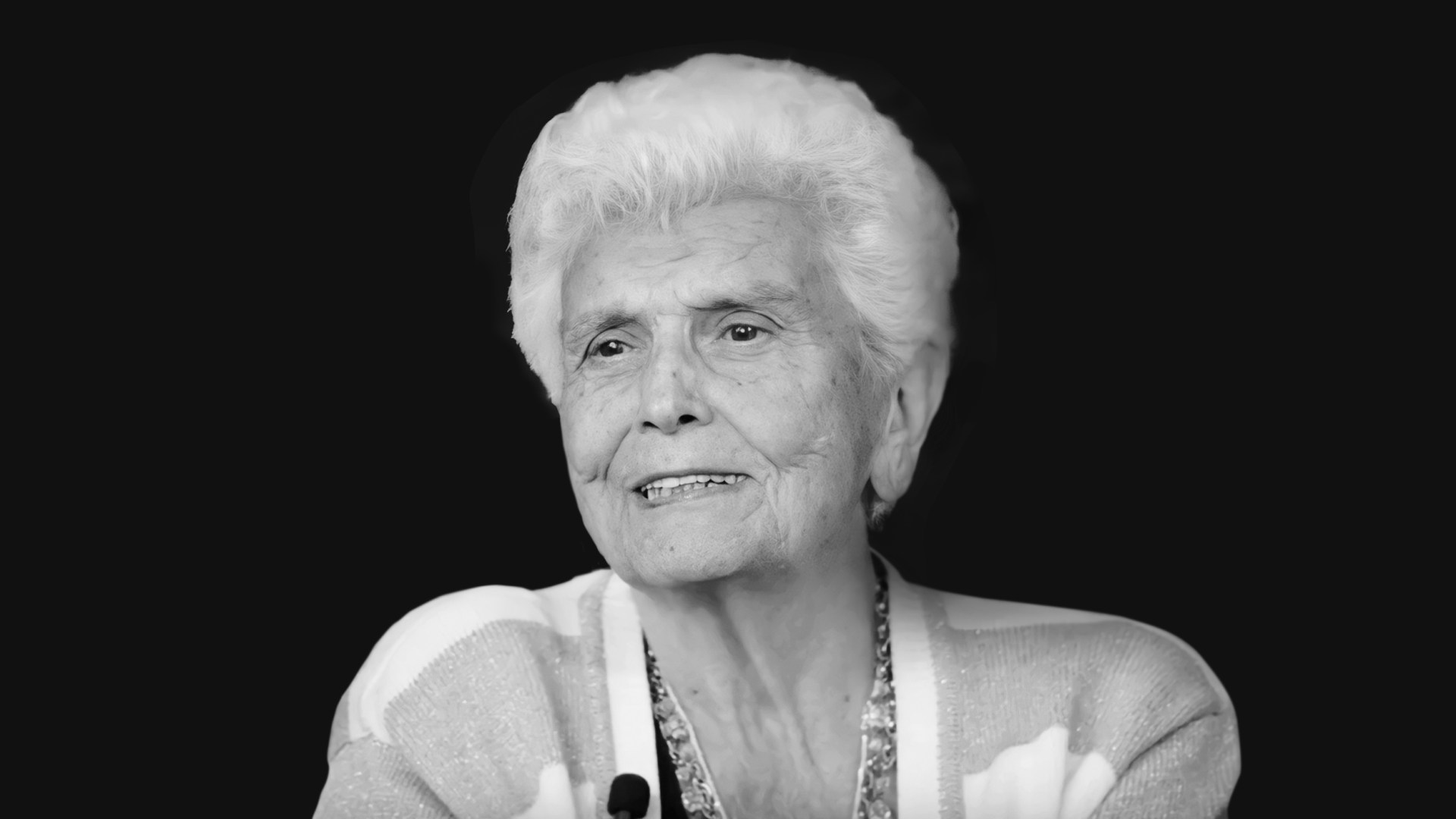

Mangham, who cofounded World Relief’s refugee resettlement program with her husband, Thomas Grady Mangham Jr., died on October 5 at age 98.

Matthew Soerens, the current direct of church mobilization for World Relief, said she was “a remarkable, faithful follower of Jesus.” Jenny Yang, World Relief’s vice president of advocacy and policy and coauthor, with Soerens, of Welcoming the Stranger, described Mangham as faithful and feisty.

“Her love for refugees, for the church, and for her Lord were contagious,” Yang said. “Her impact on the lives of those who are vulnerable will be felt for generations to come, and I know there was a huge celebration for her in heaven as so many people whose lives she touched welcomed her to her eternal home.”

Mangham was born to George and Lola Breaden in 1922. Her father was the heir of a well-off family in Greenville, Ohio, who abandoned the family business and his inheritance when he heard about the need to spread the gospel in Arabia.

Evelyn’s birth disrupted the family’s missionary call, however, because she was their third child, and the CMA had a rule that missionaries could only take two children to the mission field. George Breaden prayed and asked the denomination to make an exception and send the family anyway. The CMA waived the rule, and the Breadens went to Ma’an, Jordan, in the far reaches of the British-created Emirate of Transjordan.

“Daddy wasn’t happy in Jerusalem, Bethlehem, or Beersheba,” Mangham later recalled. “That was ‘big time.’ He wanted to be at the end of the line, so that’s where we always were.”

It was in some ways an austere childhood. Mangham didn’t have a doll and instead played with half-burnt birthday candles—the longer ones designated the father and mother, the shorter ones the children. But she also recalled joyous times running around with local children, feeding sheep, and petting camels.

Mangham was sent to school in Jerusalem with other CMA missionary children. When it was time for college, she was sent back to the US to study at Nyack College, which was then called the Missionary Training Institute.

“I was alone, and I was so scared, I can’t even remember parts of it,” Mangham said. “I’d just go back to Scripture: ‘Be anxious for nothing, but in everything by prayer and supplication, with thanksgiving, let your requests be made known to God’ (Philippians 4:6, NKJV). And I did that. And I knew that he heard me.”

Mangham met Grady, the son of an Alliance pastor, at Nyack, and the two graduated and married in 1943. Grady, who was originally from Florida, took a position at a church in Georgia for a few years, and then the couple became Alliance missionaries to Vietnam.

The CMA was the oldest Protestant denomination in the French colony. Hoi Thanh Tin Lanh Viet Nam (the Evangelical Church of Vietnam) had more than 30,000 Vietnamese Christians worshiping in about 350 congregations. The CMA also supported about 130 missionaries, who planted churches, trained pastors, translated Scripture, taught people to read and write, and provided medical care in the remote regions of the country.

The Manghams learned four languages and pushed into the interior of the country, to reach the ethnic and linguistic groups that were isolated from the rest of Vietnam. For a while they made their home base in Cheo Reo, in the Central Highlands, about 270 miles north of Saigon.

They traveled the area in jeeps—including one donated by the city of Orlando, Florida, emblazoned with decals promoting the city—over the rutted roads through the jungles. The missionaries’ treks were occasionally dangerous. In 1957, Grady shot a 12-foot tiger that had been accused of killing 200 people.

In 1962, Grady and Evelyn were briefly captured by Communist fighters and forced to listen to a two-hour lecture on class conflict and revolutionary history. The lesson ended with general well wishes for their mission, however. The Communists told the Manghams, “We know you missionaries are here only to help the people of this country.”

North Vietnamese fighters did not always look so kindly on the American missionaries’ presence, though. As US involvement in the war escalated under Presidents John F. Kennedy and Lyndon Johnson, the Manghams and other CMA missionaries occasionally had people shout at them, “Get out and stay out. You are enemies of the people.”

The Manghams served to the end of their allotted time, however, remaining in Vietnam until 1967. Then they returned to New York and went to work for the denomination. They spoke widely in support of missions and were also frequently asked to speak about the war. They supported America’s involvement in the conflict and argued it was a just cause.

When Americans withdrew in 1975 and Communists took over, the couple started getting desperate calls from people they had known who needed to get out. Mangham and two friends started making endless phone calls and found sponsors for thousands of refugees—Christians from the church in Vietnam, but also Buddhists and followers of folk religions.

Mangham told churches they should dedicate time and funds to help the refugees because they were people, because Scripture said to welcome strangers, and because it created “a mission field, backwards.”

But mostly, she argued, it was what Jesus would want.

“It’s what Jesus said, that’s all,” she once explained, quoting Matthew 25. “‘I was hungry, and you gave me something to eat. I was thirsty and you gave me something to drink. I was a stranger’—refugee—‘and you took me in.’ … It’s simple obedience.”

The refugee resettlement program began under the auspices of the CMA’s relief aid agency, Compassion and Mercy Associates. It eventually became part of World Relief. When Grady and Evelyn stepped down in 1987, the organization was resettling about 6,300 refugees per year.

The couple retired to Florida and continued to support refugee work to their ends of their lives. In her 90s, Mangham loved to throw her arms around Muslim refugees she saw in the grocery store and tell them how happy she was to see them, speaking the Arabic of her childhood.

She also frequently urged people to teach their children Scripture and learn to lean on the faithfulness of God.

“I know I’m in his hands. I’m in his hands, and he can do with me whatever he wants,” she said in 2019. “I love to do, I love to be, I love to talk, I love people, and that takes care of it.”

Mangham died a day before her 99th birthday. She is survived by her four children, Ed Mangham, Connie Fairchild, Thomas Grady Mangham III, and Patty Whalen.

“It’s not the loss that overwhelms us,” her son Thomas wrote in a tribute on Facebook. “it’s the thought that we had the honor of knowing, seeing and experiencing what it’s like to live with a Hebrews 11 hero of the faith.”

A memorial is planned for 2 p.m. on Saturday at Good Samaritan Village Church, in Kissimmee Florida.