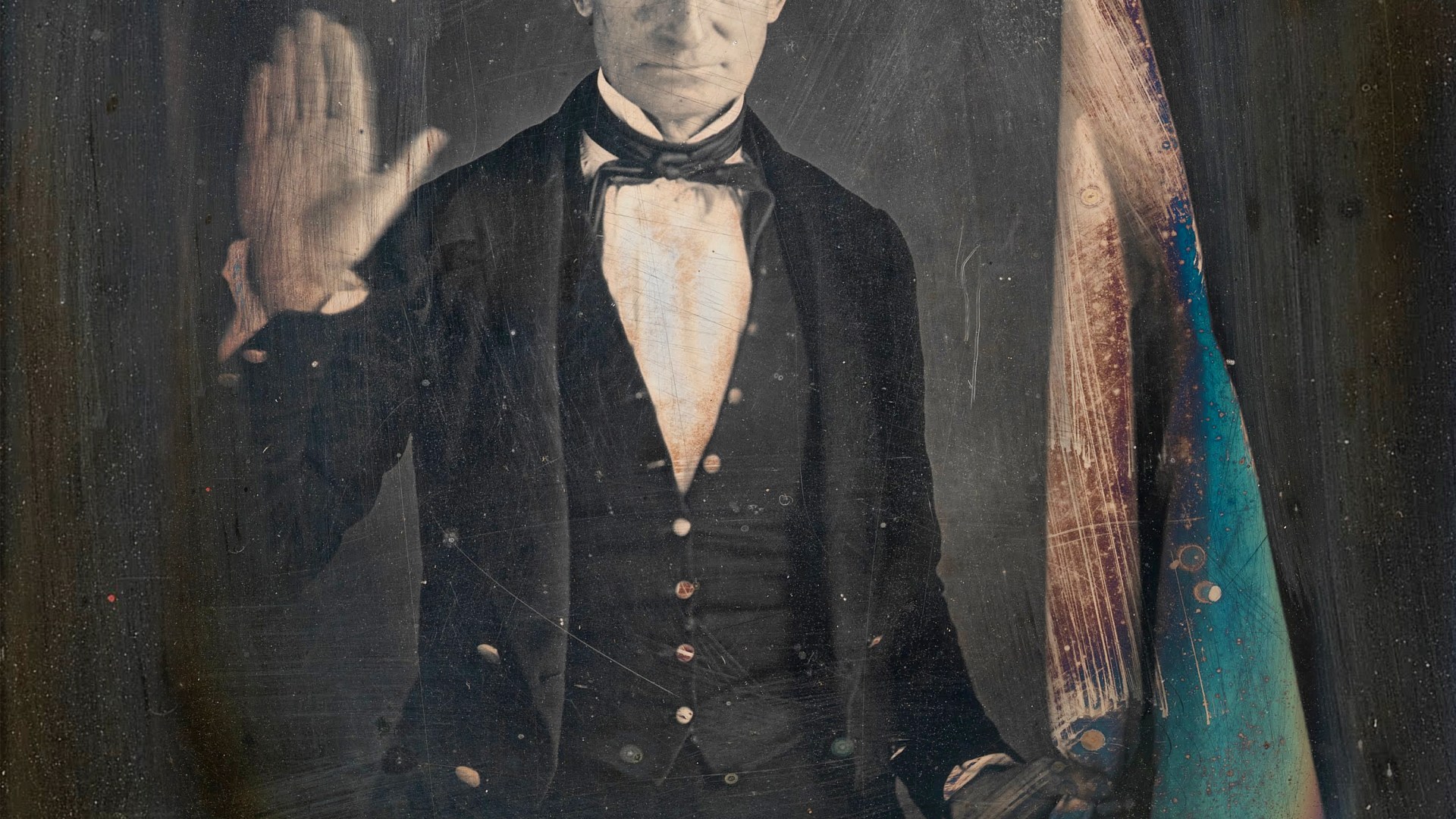

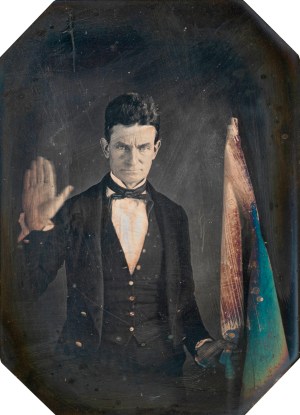

John Brown is one of the most controversial figures in the history of the United States. For some he’s a moral hero. For others, a monster.

The white abolitionist who turned to violence in an attempt to end chattel slavery in America has become a kind of bellwether for views on racial justice. One thing that has often been lost in the long tussle over the meaning of Brown, however, is his deeply evangelical faith.

Brown testified clearly to his own conversion, and he prayed that those around him would know “the grace of God through Jesus Christ.” He continually held up the Bible as the authoritative Word of God, the supreme written norm by which God binds the conscience. He urged people, “Be determined to know by experience as soon as may be, whether Bible instruction is of Divine origin or not,” convinced that if they tested the Scripture, they would discover the truth.

Brown remains controversial today. But as a white evangelical who has studied and written about his last days, those who were with him, and his religious life, I find myself hoping evangelicals will rediscover him. We could reclaim his legacy as a fervent believer who models a profoundly radical social ethic without ever wavering from his firm commitment to biblical authority.

That is to say, I dream that John Brown’s soul might march again.

His attempt to liberate enslaved people by violence failed, and he was hanged in Virginia in 1859. But throughout the war years, it seemed his spirit brooded over the divided nation. The playful soldier’s ditty about John Brown’s body “a moldering in the grave” was inexplicably taken up by soldiers and slaves alike—transformed into a raw but rousing song that invoked the evangelical extremist as the very spirit of liberty.

At the same time, “John Brown” became a curse in the mouths of white Southerners and his name made white liberals blush. Indeed, one of those liberals, Julia Ward Howe, was so put off by the abolitionist’s evangelical militancy that she conjured more respectable lyrics for “John Brown Song.” She “fixed it,” from her perspective, with the high-minded Unitarian anthem “The Battle Hymn of the Republic.”

Even today, there often is no middle ground when it comes to John Brown. In the more than 160 years since his death, the divide between his critics and his admirers often has fallen along lines of race, and sometimes politics too, although Brown has had admirers and detractors both Black and white, liberal and conservative.

Among white people, Brown was widely dismissed by the early 20th century. As American society backpedaled from the idea of Black people becoming full citizens, Brown’s reputation couldn’t help but decline. Whites in the North celebrated reunion with whites in the South and tacitly agreed to talk about the soldiers’ honor and bravery and set aside the actual issues that had separated patriots and traitors.

Slavery itself was sentimentalized in this era, with lots of popular rhetoric and images of “mammies” and “piccaninnies.” Those who benefited from the system of white supremacy were depicted sympathetically, while those who defended it were imagined to be noble.

Meanwhile Brown, who hated slavery more than he loved his own life, was portrayed as insane.

Black Americans, on the other hand, always kept a place for Brown at the table of honored memory. Frederick Douglass recalled how Brown was not only a friend of abolition, but he seemed shockingly free of the prevailing prejudices of the day. Many avowed white opponents of slavery, such as evangelist Charles Finney, condemned the institution while still insisting on racial segregation, even dividing revivals, as if it were wrong for Black people to respond to the same altar call as white people.

One place that Brown is not perceived as a brother, notably, is in evangelical history. I have yet to see one survey of Christianity in America that devotes space to Brown, or any account of evangelicalism that includes him.

In my old copy of The New International Dictionary of the Christian Church, the entry declares Brown’s “violent acts were glorified by the abolitionist extremists,” and in a later iteration of the book Who’s Who in Christian History, he is omitted altogether. As an evangelical biographer of Brown, I believe both are a mistake.

At the time of Brown’s failed attempt to end slavery by force, his faith was recognized. Those who opposed slavery for biblical reasons and shared Brown’s commitments to Christ and Scripture hailed him as one of their own. During his incarceration in Virginia, he received sympathetic letters from Calvinist clergy and laity, including the notable Covenanter pastor Alexander Milligan, who later served as chaplain at large to the Union troops during the Civil War. He was called “A Prisoner of Jesus Christ” in the Congregational publication the New York Independent.

After his death, Brown was hailed in many sermons across the North. One of those sermons, “Dying to the Glory of God,” was preached by the Wesleyan minister Luther Lee, who afterward addressed a large outdoor meeting at Brown’s graveside near Lake Placid, New York.

Perhaps the most remarkable recognition of the evangelical soul of John Brown comes from the world-famous preacher Charles Spurgeon. In 1860, shortly after the abolitionist was hanged, Spurgeon wrote to The Christian Watchman & Reflector to counter rumors that he was allowing US publishers to redact statements about slavery from his sermons to make them more palatable to American readers.

Spurgeon said he hadn’t addressed slavery, because he was preaching in Great Britain where it was illegal. But his position should be clear: He would not partake of Communion with a slaveholder, and were a slaveholder to come into his neighborhood, that man would receive a mark “that he would carry to his grave, if it did not carry him there.”

If that violent response reminded anyone of Brown, Spurgeon had no qualms about the comparison. Brown was “immortal in the memories of the good in England,” he wrote, adding, “In my heart he lives.”

Brown won the admiration of some other evangelicals as well, including Russell Conwell, the Baptist clergyman who founded Temple University in Philadelphia and became the namesake of Gordon-Conwell Theological Seminary.

In the 20th century, the minister Clarence E. Macartney, one of the main leaders with J. Gresham Machen of the conservative side of the fundamentalist-modernist division in the Presbyterian church, cited Brown numerous times in his sermons. He even worked to preserve one of Brown’s jailhouse letters, giving it to Geneva College’s archival collection.

These evangelicals were right to see Brown as one of them. He was raised in a devout Congregational home in Ohio’s Western Reserve, sat under the preaching ministry of a Presbyterian pastor, and was trained in the Westminster Shorter Catechism. He professed faith in Christ at 16 years old. After conversion he became, as he later wrote, “ever after a firm believer in the divine authenticity of the Bible” and “became very familiar & possessed a most unusual memory of its entire contents.” Indeed, biblical quotations fill almost every page of his correspondence.

Despite efforts on the part of some historians to portray him as heterodox, Brown’s Calvinism was conventional, more influenced by the Puritans of yesteryear than by the novelties of New England Theology. What distinguished his Christianity from that of some in America (then and now), was a thorough dedication, as he once put it, “to better the condition of those who are always on the under hill side.” This activism was deeply evangelical and deeply shaped by his theological beliefs.

Writing of his youth, Brown recalled how he had witnessed a white man beating a Black child with an iron shovel. He said he could not help but ask himself if God was not also the father of the victim of that atrocious violence. His answer was yes, and that shaped the rest of his life.

As a teenager, Brown briefly considered studying for the ministry in New England, but an uneven primary education and chronic inflammation of his eyes discouraged these aspirations. Yet his commitment to Christian faith never wavered. This is perhaps most clearly seen in his relationships with his children, several of whom rejected Christianity as young adults.

When his namesake declared himself a spiritualist in 1853, Brown dashed off a six-page tour de force of Scriptures, from Old to New Testament, including Jeremiah’s appeal, “Turn, O backsliding children saith the Lord.” To another apostate son, Brown wrote, “I do not feel ‘estranged from my children,’ but I cannot flatter them, nor ‘cry peace when there is no peace.’”

After embarking on his antislavery campaign in 1857, he gave a Bible to his youngest daughter, Ellen. Inside he wrote, “May the Holy Spirit of God incline your heart in earliest infancy to receive the truth in the love of it and to govern your thoughts, words and actions by its wise and holy precepts.”

Another place Brown’s evangelical sentiments come through clearly is the words he wrote in his last days. After being sentenced to death, he wrote to his sisters, “Can you believe it possible that the scaffold has no terrors for your own poor, old unworthy brother? I thank God through Jesus Christ my Lord it is even so.”

Two days before he was hanged, Brown wrote a long letter to his family, declaring how he had been “travailing in birth” for them, praying that none would “fail of the grace of God through Jesus Christ, that no one of you may be blind to the truth.” Urging them to take up the Scriptures as their “daily & nightly study,” he appealed that they would not rely on their “own vague theories framed up” instead of the Word of God.

“Oh,” he appealed, “do not trust your eternal all upon the boisterous Ocean without even a Helm or Compass to aid you in steering.”

Brown was forced by his impending death to consider whether the plan to take up arms to destroy slavery had been a mistake. Had he failed? To answer, he turned again to faith.

“I believe most firmly that God reigns,” he wrote to a clergyman from death row. “I cannot believe that anything I have done, suffered or may yet suffer, will be lost to the cause of God or of humanity. … I now feel entirely reconciled to that … for God’s plan was infinitely better.”

One may, of course still question Brown’s tactics and the way he put his faith into action in “Bleeding Kansas” and the raid on Harpers Ferry. I think the evidence shows that he was not driven, as has so often been alleged, by crazed bloodlust or violent megalomania.

Indeed, Brown was actually “averse to the unnecessary shedding of blood,” according to a New York Times account from the time, and ordered his raiders to exercise great care lest innocent civilians be harmed. The only antislavery reporter to cover the abolitionist’s last days, an undercover journalist for the New York Tribune, characterized Brown’s plan as the “rescue of a great number of slaves,” arguing he had no interest in maintaining “a warlike position in Virginia for any definite period of time.”

When a jury of slaveholders found him guilty of insurrection, Brown rejected it, declaring in court that he had no such aim. One of his sons claimed that the intention with the raid was not to kill white slaveholders and spark a violent uprising, but “open the way for slaves in increasing numbers to escape from their masters.” Brown hoped that, given a chance, people in bondage would flee. If enough of them did, that would “render slavery uncertain and unprofitable.”

The first draft of history, however, was mostly written by the proslavery press. The initial interpretation of Brown’s actions was crafted by people who believed that “all men are created equal” was a lie.

I have found that much of the real story of John Brown has thus been lost to caricature and partisan interpretation, a selective reading of history that withholds the same considerations often granted to other figures in Christian history.

Perhaps we might reconsider the words of Preston Jones, who once wrote in CT: “Because Christian readers, writers, or teachers of history know that sin infects everything, they are able to exercise charity, compassion, and understanding toward historical figures who made vast errors.”

Of course, I do not believe John Brown’s “errors” were “vast” in comparison to white Christians who secured the shackles of the slave, fought to suppress native peoples, and enforced racial oppression. But I do think we could ask ourselves why Brown cannot at least receive the same charity that evangelicals have extended to others who were, as they say, “men of their time.”

In our time, white evangelicals seem to be in dire need of good examples of people who were transformed by their faith to rise above pedestrian racism—because, not in spite of, their unshakable commitment to the authority of Scripture. Why not John Brown? Why not the most esteemed white man in Black history?

“Wherever there is a right thing to be done,” Brown liked to say, “there is a ‘thus saith the Lord’ that it shall be done.”

Surely that’s a spirit that should go marching on.

Louis A. DeCaro Jr. is professor of Christian history and theology at Alliance Theological Seminary and the author of several books on John Brown. He also hosts the podcast John Brown Today.