In the 1930s and 1940s, two of the most widely heard preachers in America were also two of the most unlikely candidates for such fame. Fulton Sheen and Walter Maier were both sons of immigrants, both seminary professors specializing in ancient languages, and both from historically oppressed religious traditions. But through the power of radio—which was then a novel mass medium—they reached millions of listeners and ultimately reshaped the trajectory of conservative religion in America.

Ministers of a New Medium: Broadcasting Theology in the Radio Ministries of Fulton J. Sheen and Walter A. Maier

InterVarsity Press

368 pages

$27.78

Their story is told in Kirk Farney’s compulsively readable dual biography, Ministers of a New Medium: Broadcasting Theology in the Radio Ministries of Fulton J. Sheen and Walter A. Maier. Maier, born to German immigrants, showed early academic promise and attended Concordia Seminary (the flagship seminary of the Lutheran Church—Missouri Synod) before completing a PhD at Harvard Divinity School. Being part of a still largely German-speaking Lutheran church was an obstacle given public suspicion towards German-American immigrants during and after World War I. Maier, seeking to establish his patriotic bona fides and to “register his disapproval of the Prussian military clique,” joined the US Army as a chaplain. Yet he promptly pushed the limits of official toleration by ministering to German prisoners of war.

After the war, Maier joined the faculty at Concordia Seminary, where in 1924 he convinced the school to apply for a radio license, financing station KFUO with money fundraised from faculty, students, and alumni. Maier’s early adoption of radio as a means of outreach quickly paid off. Within a few years, his show, The Lutheran Hour, aired on stations nationwide, first on the CBS network and then on MBS, reaching an estimated audience of 20 million by the time of Maier’s death in 1950, making him the most-heard religious broadcaster in America at the time.

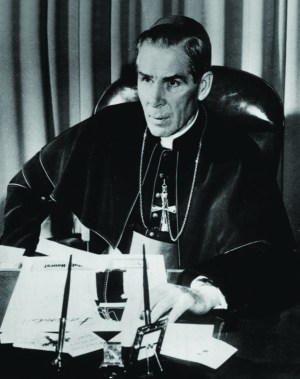

Similarly, Fulton Sheen, born to an Irish-Catholic immigrant father, had to navigate public hostility towards religious outsiders. While Maier faced exclusion as a second-generation German immigrant, Sheen was a target for enduring American anti-Catholic prejudice. He studied ancient languages at St. Viator College and the Catholic University of America before earning a PhD while studying Thomistic philosophy at the University of Louvain in Belgium. After a brief spell as a small-town curate, he began a professorship at Catholic University and quickly became an in-demand speaker at church conferences, school commencements, and Knights of Columbus ceremonies.

Thus, when the NBC network asked the National Council of Catholic Men in 1930 to select speakers for a dedicated Catholic spot on the network’s lineup, Sheen was a natural choice. His winsome and yet firm approach to explaining the Catholic faith was needed after the eruption of anti-Catholic prejudice following the failed 1928 presidential bid of Al Smith, the first Catholic nominee of a major American political party. Almost overnight, Sheen’s sermons reached over seventeen million Americans, making him a household name and leading Pope Pius XI to bestow the honor of papal chamberlain.

Ending the religious civil war

Contemporary observers compared Maier’s and Sheen’s preaching acumen to the famously “golden-mouthed” early church father John Chrysostom, high praise indeed for these two scholars of ancient languages. Today, we might instead say that they were the Billy Grahams of their era, anticipating Graham’s combination of anti-communist rhetoric, celebrity endorsements, and a commitment to traditional doctrines in implicit opposition to modernist theology.

During World War II, Maier condemned “atheistic Communism” to “the same hell to which it leads,” while Sheen warned his audience to be wary that their wartime Russian allies might be a “Trojan Horse” for public acceptance of communism. Both preachers also focused on offering a positive appeal while providing accessible explanations of traditional Christian doctrines like atonement and biblical inspiration. Privately, both Sheen and Maier were quite critical of liberal preachers like Harry Emerson Fosdick, but while on the air they avoided making explicit attacks on other religious groups except in the broadest of terms. Farney quotes historian Robert Handy calling Maier the “missing link” between the evangelistic bookends of the 20th century, Billy Sunday and Billy Graham.

But Sheen and Maier shared a deeper similarity. After a lifetime of navigating exclusion—whether anti-Catholic or anti-ethnic—they had each developed a deep-seated commitment to pluralism and religious liberty. It was not hard for them to remember that they were strangers in a still-strange land even as they used a new mass-communication medium to carve out a more tolerant home. This is one of the powers of a novel mass media; it allows previously marginalized groups—who are often more willing to experiment given that the older pathways to influence are barred to them—to win greater public acceptance.

Courtesy of Lutheran Hour Ministries

Courtesy of Lutheran Hour MinistriesIt is telling that the Lutheran Laymen’s League—a core backer of Maier’s The Lutheran Hour—worried that the radio ministry of the Jehovah’s Witnesses reached more people each week than there were Lutherans in America. Thus, Maier seized on radio as an opportunity for Lutherans to abandon their “inferiority complex” and their “German complex” to “work for the upbuilding and strengthening of the two greatest institutions in the world, the American Government and the Lutheran Church.” Radio was a vital mechanism by which peripheral religious groups could assert social belonging and lay claim to the oft-unfulfilled American promise of religious liberty.

Religious radio also played a fundamental role in the forging of new religious identities, creating formations that would have seemed alien to prior generations. Farney highlights the way that Maier and Sheen contributed to the gradual decrease of the longstanding interfaith prejudice between Catholics and Protestants. A third of Sheen’s audience was non-Catholic, and both men routinely received complimentary listener letters from the opposite tradition.

This was by design. As Sheen said, “A few decades ago Christianity’s struggles were more in the nature of a civil war…between Methodists and Presbyterians, Lutherans and Anglicans, and in a broader way between Jews, Protestants, and Catholics.” But now, “face to face with an invasion, an incursion of totally alien forces who are opposed to all religion and all morality”—a not-so-veiled reference to Communism—the religious civil war must end. Maier and Sheen were participants in the creation of what historian Kevin Schultz has called “Tri-Faith America,” which welcomed both Jews and Catholics into the previously Protestant religious consensus via the Cold War logic of national resistance to atheistic totalitarian encroachment. Although a fuller rapprochement between Catholics and Protestants would not come for another generation, Maier and Sheen prepared the way for a time when “Judeo-Christian” would become a political and religious identity framed in opposition to secular humanism.

The Lutheran Hour and The Catholic Hour also played vital roles in establishing what it meant to be Lutheran and Catholic in America. Sheen’s broadcasts helped break down the old ethnic divisions between Catholics—as Poles, Italians, Irish, and other immigrant communities felt joined via a broader communion of the airwaves. Likewise, Maier encouraged distinctively German Lutherans to think of themselves as part of a larger, evangelical whole. His sermons routinely quoted non-Lutherans from a wide range of denominations, including Fanny Crosby, Charles Wesley, and Dwight Moody. Furthermore, Maier played a significant role in the creation of the National Association of Evangelicals; as I have written elsewhere, the very idea of a “new evangelicalism” was rooted in a pragmatic defense of the right of religious broadcasters to purchase radio airtime. Thus, over the course of just a few decades, religious radio fundamentally reshaped what it meant to be Lutheran, Catholic, evangelical, and Christian in America.

Maier’s and Sheen’s role in the development of new, imagined religious communities hinged on the unique power of radio to create the impression of intimacy. Farney calls it “perceived intimacy” to describe the way listeners felt a personal relationship with broadcasters, people who they had never met before but whose voices still suffused their homes and lives. They responded by mailing in letters and donations, sharing their fears and hopes with their favorite radio preachers. Sheen had a full-time staff of 22 people dedicated to opening and answering the three-to-six thousand letters he received from listeners a day, while Maier got 30,000 letters a week. Both Sheen and Maier routinely read excerpts from listener letters on the air, even using them as the basis for sermon topics.

WikiMedia Commons

WikiMedia CommonsThis anticipated the talk radio format that would flourish later in the 20th century, along with its capacity for creating a sense of shared community and perceived intimacy between broadcaster and listener. While that intimacy might seem artificial at best and dangerous at worst, given the pernicious influence of interwar radio demagogues like the antisemitic Father Charles Coughlin, Maier and Sheen serve as a reminder that the same technology could be used for better ends. And today, in an age when politicians and church leaders can use social media to bypass traditional media gatekeepers and speak directly to a new mass audience, both sides of that coin are worth remembering.

Optimism and wonderment

If there is one weakness in Farney’s analysis, it is that he attributes the success of religious radio to the unique genius of the individual broadcasters rather than to broader structural factors. Thus, he implies that it was something about Maier’s and Sheen’s “biblical, theological, and topical content” that won them a mass audience. Yet while it is true that their learned irenicism aided their success, it was necessary because of the requirements of institutional gatekeepers at the major radio networks and the Federal Radio Commission. Farney does parse the distinction between free “sustaining” airtime given away to favored broadcasters (including Sheen) by the major networks and those broadcasters (like Maier) who merely sought the right to purchase airtime.

But in either case, Maier’s and Sheen’s decision to avoid direct attacks on other religious groups complied with the mandates of government regulators and network executives who believed that radio should serve the national interest by decreasing sectarian tensions, promoting Americanism among immigrant communities, and avoiding radical political opinions. In other words, Maier and Sheen conformed to the structural incentives erected by the radio industry and its regulators, who were interested in creating model, moderate citizens. By contrast, other religious broadcasters, like the muckraking Reverend Robert “Fighting Bob” Shuler on Station KGEF in Los Angeles, lost access to the airwaves for intervening in local politics and criticizing the Catholic Church. The growing post-World War II religious consensus exemplified by Sheen and Maier was itself a product of restriction, exclusion, and regulation, and not merely the product of their powerful personalities.

While the idea of technological disruption in American religion is hardly novel, the sense of optimism and wonderment that accompanied the rise of religious radio feels alien today. Farney opens with a compelling description of Maier’s inaugural broadcast on KFUO radio at a ceremony at Concordia Seminary, where a biplane zoomed overhead in what one observer described as “a conjunction of a living past with the vibrant present.” Or as a German-language Lutheran magazine wrote, “Times change, and we change with them. But God’s Word remains forever.” Some were wary of deploying the new technology for kingdom purposes, like Maier’s fellow Concordia professor Theodore Graebner, who warned of introducing the temptation of radio, “widely employed in the secular, commercial world,” into Christian homes.

But Maier and Sheen were techno-optimists who saw that radio could be a tool for effective evangelism and pastoral edification, a veritable “Church of the Air” (to borrow the CBS network’s name for its regular religious programming in the 1930s). As Sheen put it, “Radio has made it possible to address more souls in the space of thirty minutes than St. Paul did in all his missionary journeys.”

It is hard to imagine conservative Christians in the 21st century sharing that same sense of optimism about digital and social media. Rather, digital substitutes or complements for church life—streaming services, Zoom small-group meetings, augmented-reality gatherings—are often regarded as merely temporary measures for dealing with pandemic restrictions or as dangerous alternatives to a religious life centered around in-person gatherings and a traditional worship calendar. Yet Maier and Sheen serve as a reminder that it is possible to embrace a new technological medium with tempered eagerness—and to immense and salutary effect.

Paul Matzko is a research fellow at the Cato Institute and the author of The Radio Right: How a Band of Broadcasters Took on the Federal Government and Built the Modern Conservative Movement.