Stuart Briscoe preached his first sermon at 17.

He didn’t know much about the topic assigned him by an elder. But he researched the church of Ephesus until he had a pile of notes and three points, as seemed proper for a sermon. Then he stood before the Brethren in a British Gospel Hall and preached.

And preached. And preached.

He kept going until he used up more than his allotted time just to reach the end of the first point and still kept going, until finally he looked up from his notes and made a confession.

“I’m terribly sorry,” he said. “I don’t know how to stop.”

Briscoe recalled in his memoir that a man from the back shouted out, “Just shut up and sit down.”

That might have been the end of his preaching career. But he was invited to preach again the next week. Then he was put on a Methodist preaching circuit, riding his bike to small village churches where a few faithful evangelicals would gather to worship and encourage the fumbling young preacher with exclamations of “Amen” and “That’s right, lad.”

In the process Briscoe became a better preacher, discovered he had a gift, and was encouraged to develop it. He ultimately preached in more than 100 countries around the world and to a growing and multiplying church in America.

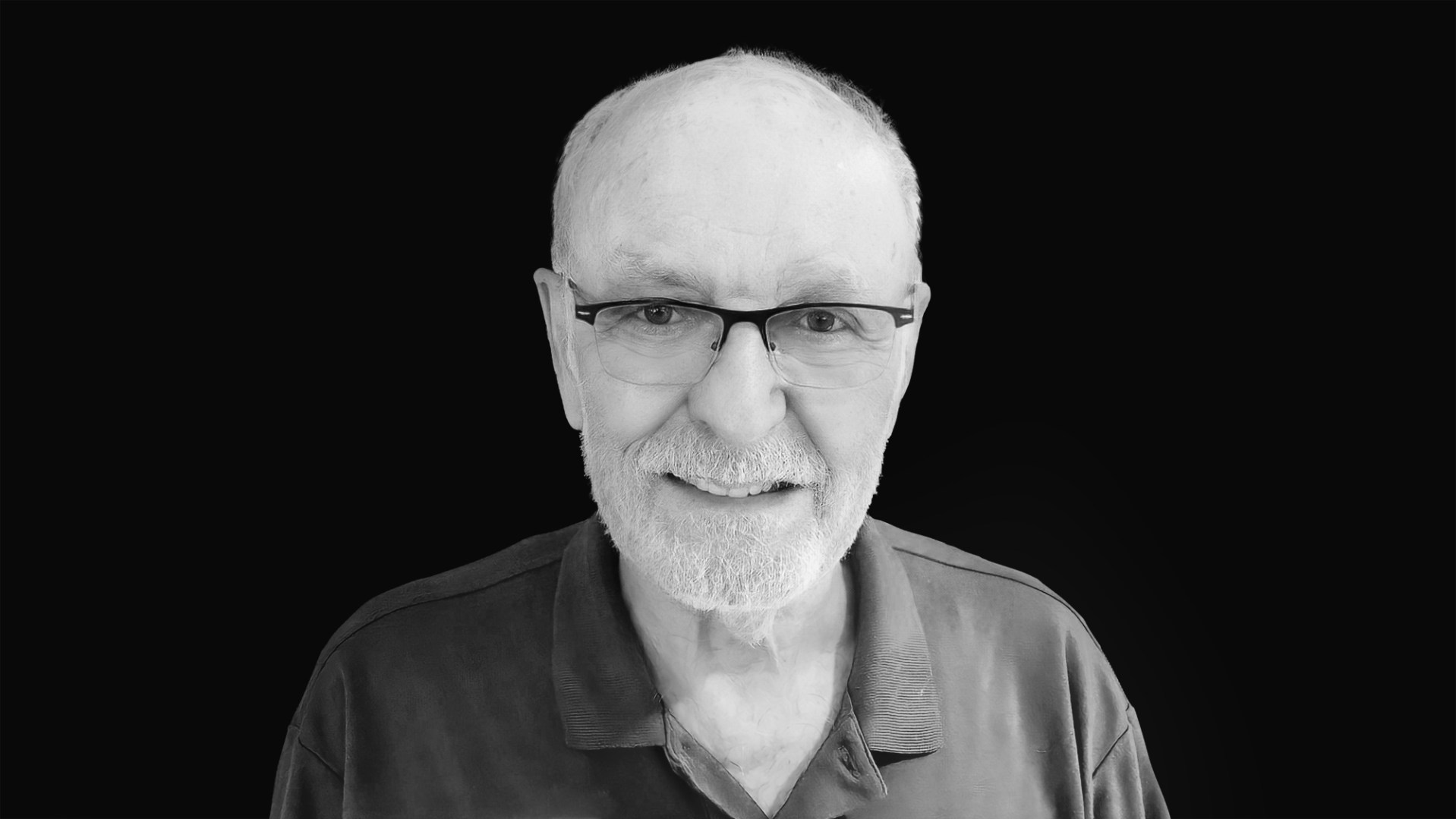

When Briscoe died on August 3 at the age of 91, he was known as a great preacher who spoke with clarity, loved the people he preached to, and a had deep trust in the work of the Holy Spirit.

“My primary concern in preaching is to glorify God through his Son,” he once wrote for CT. “I’ve worked hard to preach effectively. But I’ve also learned to trust as well. Farmers plow their lands, plant their seed, and then go home to bed, awaiting God’s germinating laws to work. Surgeons only cut; God heals. I must give my full energy to doing my part in the pulpit, but the ultimate success of my preaching rests in God.”

Briscoe was born on November 11, 1930, as the Armistice Day parade of World War I veterans marched past his house. He was born at home in Millom, England, a village north of Manchester, in the Lake District. It was a town, Briscoe noted, that John Wesley once described as a “habitation of thieves and robbers.” His parents, however, were grocers and devout Brethren.

A reminder of courage

Stanley and Mary Briscoe named their eldest son after the missionary Eva Stuart Watt, who wrote a book about being orphaned by her missionary parents and how she remained committed to the cause of proclaiming the gospel.

“‘Stuart’ to them spoke of missions and jungles and people without God,” Briscoe wrote. “In their minds my name was a reminder that courage was needed, that commitment was necessary, that sacrifice was normative, that service was lifestyle, and that life was earnest.”

As a child, Briscoe found he needed courage to be a nonconformist. Every Sunday he and his parents marched past the Anglican Church, which approved by the state and respected by the culture, carrying their Bibles to a small building called the Tin Chapel, which was seen by everyone as odd.

World War II began just before Briscoe turned 9, however, and the year he was 10 the town filled up with soldiers from across the British Empire. Many of them found their way to the Tin Chapel. Briscoe learned that his small faith community was actually part of a global evangelical movement. Those brave, funny, and enthusiastic young men from Australia, India, South Africa, and Canada shared his parents’ love and trust for the God of the Bible.

Briscoe was especially influenced by one artillery captain who regularly asked him, “What’s your best thought today, Stuart my boy?”

During an air raid, Stuart wrote in his memoir, the captain taught him how to calculate the distance of falling bombs by timing the difference between the flash of light and the thump of an explosion. As search lights probed the darkness and anti-aircraft filled the sky with tracer bullets that looked “like strings of burning sausages,” the captain also taught Briscoe how to find courage in a crisis. He pointed at the Scripture verse Briscoe’s mother had framed on the wall: “Thou wilt keep him in perfect peace, who is stayed on thee” (Isa. 26:3, KJV).

Briscoe graduated from school at 16 and found his way into banking. He earned a reputation for trustworthiness and was promoted and promoted again, but he felt pulled increasingly toward ministry. He was invited to preach to the Brethren, then on the Methodist circuit, and then started to work with Torchbearers International, associated with Keswick theology, teaching and training people to allow Christ to live in them.

A live of service to God

He was encouraged to pursue Christian service by a young Cambridge University graduate he met in the 1950s. Jill Ryder had been very active with InterVarsity Christian Fellowship during her time at university and told Briscoe that she was only interested in having a romantic relationship if the man was committed to living a life service to God. Briscoe was interested in that. He told Jill that was his goal in life too, and they were married in 1958.

Early in their marriage, Stuart got to see what Jill meant by a full life of Christian service when the popular coffee shop across the street from their home in Manchester unexpectedly closed. Jill went over and invited all the young people home with her. They trooped up to her apartment and she asked them about their lives and told them about Jesus, while also caring for her first child. When Stuart got home, he later recalled, there were so many young people in the apartment that the door wouldn’t open. “Sorry mate,” said a young man sitting against the door. “It’s full.”

Shortly after that, Briscoe turned down a promotion at the bank. The top managers called him in for a meeting and asked what his ambitions were.

“I want to preach the gospel,” Briscoe said, “to as many people as possible.”

He resigned and went to work for Major Ian Thomas, head of the Capernwray Bible School and Torchbearers. Briscoe spoke at the Keswick Convention alongside the evangelical giant John Stott and was then asked if he would be willing to travel regularly, preaching on a global circuit.

Briscoe made his first trip to the US in 1964, preaching in Chattanooga, Dallas, Chicago, and New York. His second trip, in 1971, changed the course of his ministry.

A call to love the church

A friend told him that he thought Briscoe’s preaching was too individualistic. He didn’t care enough about the church. Briscoe protested that he did care about the church—the church was, after all, the bride of Christ. But the friend pointed out Briscoe only loved an abstract idea of the church, a mystical, and invisible bride, where the New Testament from Acts to Revelation is full of very real churches with specific locations and contexts. Briscoe, always on the road, didn’t love a church like that.

Feeling convicted, the 40-year-old preacher was surprised when he went to speak at a nondenominational church in Milwaukee and the elders of the Wisconsin congregation asked him out of the blue to be their minister. Briscoe said he’d pray about it.

Jill, tired of her husband always being on the road, said, “You pray while I pack.”

Transitioning from a preaching circuit to pastoral ministry was not easy, but under Briscoe’s leadership, Elmbrook Church started to grow. Briscoe didn’t have a model that he was trying to follow. He just knew he was committed to preaching the Word, loving the people, and praying the Spirit would move.

The church filled with lapsed Catholics inspired by the Second Vatican Council to delve deeper into Scripture, Briscoe wrote in his memoir. And there was an influx of young “Jesus people” who had found faith while wandering through the hippie movement and then got invited to something called “The Friday Night Thing” by a married couple in the congregation.

Melding the historic General American Reformed Baptists congregation that had founded Elmbrook with the hippie Christians, former Catholics, and some Lutherans wasn’t always easy, but within a few years Elmbrook was the largest evangelical church in Wisconsin.

“Sometimes, I think, too much emphasis is laid on the effectiveness of pastoral leadership in a church at the expense of lay leadership and congregational involvement,” Briscoe wrote. “A church where the Spirit of God is actively and freely at work will discover that life springs where water flows.”

Briscoe learned again, as a pastor, that there’s a time to “Just shut up and sit down.” The health of the church should be measured less by the quality of his latest sermon, Briscoe argued, than the way the congregation was formed to follow Christ.

He was thrilled when he came back from a trip in the early 1980s to find part of the church full of furniture. He asked a woman he didn’t know what was happening and she said, “It’s for our refugee ministry.” That was the first Briscoe heard of the church’s refugee ministry, which went on to host Hmong and Lao families fleeing the violence in Cambodia.

Confidence in the future

Briscoe also continued to hone his preaching skills, eventually becoming a sought-after expert on how to preach difficult and controversial sermons, how to deal with mistakes, and how to evaluate the success of preaching. He became a regular contributor to Preaching Today.

With the help of a TV news reporter who attended Elmbrook, Briscoe also started a TV and radio ministry broadcasting his sermons in the Midwest and eventually across the US. Today, his sermons can still be heard on the radio from Alaska to Alabama, as well as online with a mobile app.

Briscoe stepped down from pastoral ministry in 2000. He said at the time he’d continue to serve however he could for as long as he could, but he also believed he could trust the work of the Spirit, and he knew a rising generation of evangelicals was carrying the gospel like a torch held high.

“I have seen the future in the set of the jaw, the intensity in the eyes, the devotion to Jesus, and the love for people in the next generation of believers on every continent,” he wrote.

For himself, he told the Milwaukee Journal Sentinel, he hoped people would say he served God in his generation “and now has fallen asleep and is ready to meet his Lord.”

Briscoe is survived by his wife, Jill, and children, Dave, Judy, and Pete. Arrangements for a celebration of his life will be announced soon.