I remember watching with great interest as President Biden signed the Emmett Till Antilynching Act into law on March 29, 2022. After 200 failed attempts over a 100-year span, legislators finally succeeded in outlawing lynching as a federal crime.

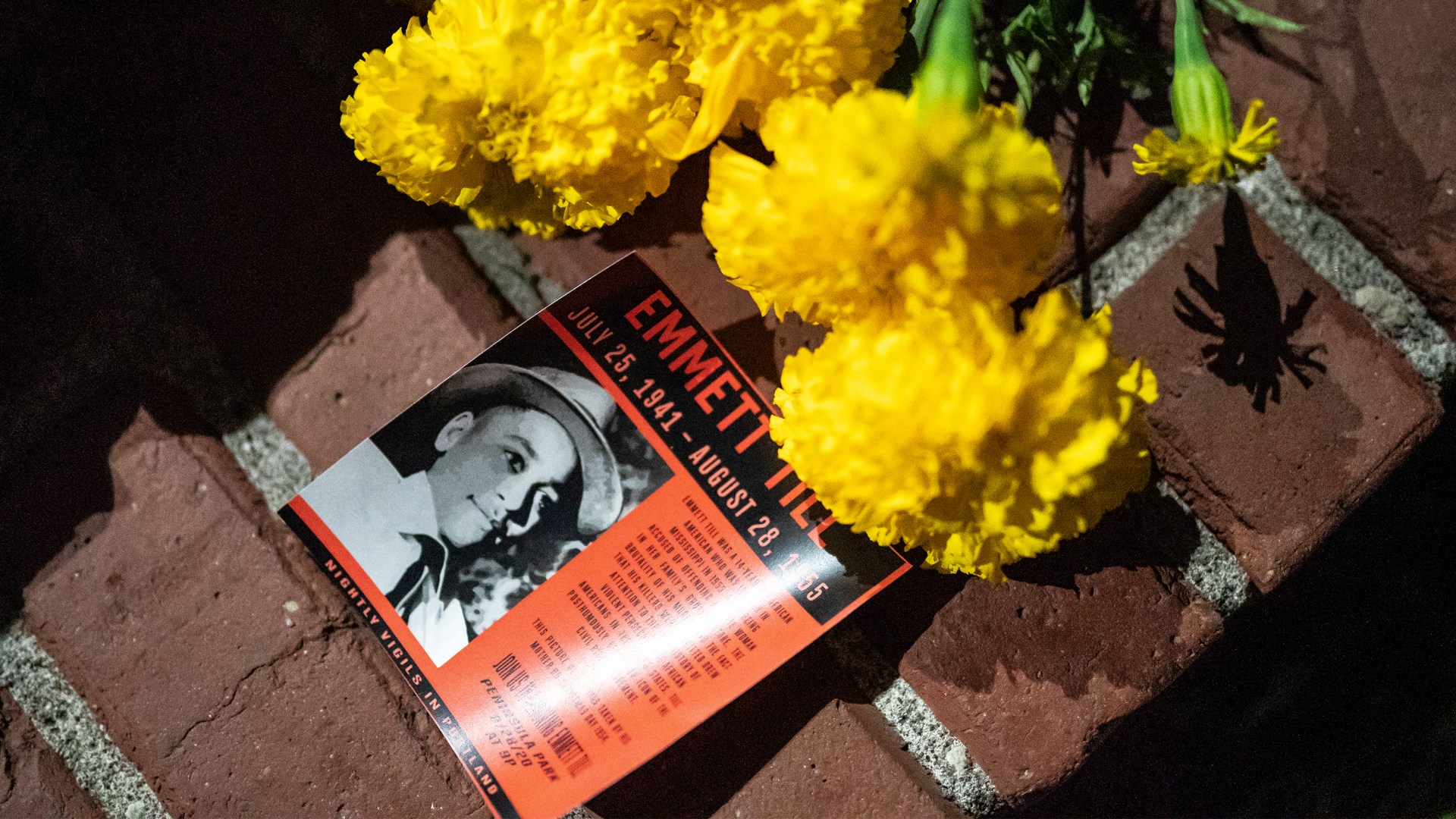

My interest in the bill centered on legislators’ decision to name it in honor of Emmett Till, the 14-year-old Black youth from Chicago’s South Side. His 1955 lynching inspired a generation of activists for racial justice. Till ran afoul of revered Southern traditions when he whistled at a white woman, Carolyn Bryant, while visiting family in Mississippi. In response, Bryant’s husband, Roy, and his half-brother John William Milam abducted Emmett from his family’s home, tortured him, cut his life tragically short by a single gunshot to the head, and then discarded his lifeless body in a nearby river.

He was so disfigured after their vicious assault that his family was able to identify him only by the ring he wore on his hand. Despite overwhelming evidence and even confessions, Bryant and Milam were never held accountable for Till’s lynching.

His mother, Mamie Till-Mobley, brought his mutilated body back to Chicago. Against the wishes of local city officials, she made the courageous choice to hold an open-casket funeral for her son, deciding to “let the world see what they did to my boy.”

The outcry following his death provided a catalyst for the civil rights movement. Rosa Parks would later explain, “I thought about Emmett Till, and I couldn't go back [to the rear of the bus].”

Almost 70 years later, we continue to retell Till’s story in the face of racial controversy.

The recent feature-length film Till, starring Danielle Deadwyler, introduces a new generation to these events and their impact on our nation. Dave Tell, author of Remembering Emmett Till and lead investigator on the Emmett Till Memory Project, told me recently that the story has become more than a tragic moment in an anguished racial past. It provides a vital lens for us to understand our troubled racial present.

Several years ago, as the nation wrestled to make sense of the racist murder of George Floyd, historians and activists turned to the story of Till. Similarly, we in the church need to consider what Till’s death teaches us as we seek to empower God’s people to reflect God’s kingdom. The specter of white supremacy and anti-Black racism still divides the church. And Christians still face constant temptation to dismiss racist violence as the actions of “a few bad apples.”

Till’s death teaches us that racist violence doesn’t happen in a vacuum. It’s the product of a people who have grown apathetic to the plight of fellow citizens on the margins. Fourteen-year-old Emmett wasn’t killed because he whistled at a white woman. He died because he lived in a society that relegated Black people to the status of second-class citizens and justified anti-Black violence as a way to maintain the existing social order.

The apathy of the nation and the church to the plight of oppressed Black people fostered a racial climate in which two white men could lynch a 14-year-old Black child with impunity. It normalized this behavior.

Unfortunately, the logic that informed these actions hasn’t been eradicated; it’s only evolved.

We’ve lived through a season of racial reckoning tied to the racially motivated killings of Breonna Taylor, Ahmaud Arbery, and Floyd. Parishioners and church leaders around the nation watched the video of Floyd’s lynching with shock and horror. We decried his death. We rushed to purchase books on race and host “diverse” conferences on racial reconciliation that often amounted to little more than racial capitalism on the conference circuit.

Even though we’re only two years removed from that time of public outcry, the church is already at risk of embracing a similar apathy. When it’s time to engage the everyday forms of racism that fuel disparities in health care, education, and employment, some Christians duck behind phrases like “Just preach the gospel.”

In that context, Till’s death summons us to courageously expose and testify to the extreme daily realities facing those on the margins. Doing so involves interrogating the cultural and ecclesiastical investments in racism and white supremacy that lurk in the shadows of “Just preach the gospel” and other similar phrases.

Trying to preach the good news apart from the pursuit of justice is like trying to preach Christianity without Christ. It sounds nice but lacks the essence of the gospel we claim to represent. It normalizes racism.

This tendency toward apathy is not new but recursive. During the latter half of the civil rights movement, Dr. King grew increasingly distressed as he recognized the nation’s racial indifference.

He wrote,

For the vast majority of white Americans, the past decade—the first phase—had been a struggle to treat the Negro with a degree of decency, not of equality. White America was ready to demand that the Negro should be spared the lash of brutality and coarse degradation, but it had never been truly committed to helping him out of poverty, exploitation or all forms of discrimination.

Just as the nation’s appetite for racial justice diminished during the latter stages of the 1960s, our enthusiasm wanes today.

But Till’s lynching provides us with a grammar to engage injustice. Our words in the pulpit and the community should testify powerfully against the sinful legacy of racism and white supremacy.

Emmett’s death occurred in part because Sunday after Sunday, his murderers sat under Bible Belt preachers who failed to disrupt the white supremacist, colonialist attitudes shaping their congregants’ view of Black people.

Our Christian witness doesn’t allow for this kind of indifference. We cannot stand silently in the face of sin and at the same time pretend to be in solidarity with our Savior. Every day, we wake up to a world on fire. Geopolitical conflict, devastating poverty, colonial legacies, and racist violence threaten the tattered remains of our world and the divided mind of the church.

Along with many other stories, Till’s death reminds us that if we want to embrace our Christian calling as salt and light, we simply can’t afford to avoid social decay or darkness.

Theon Hill serves as an associate professor of communication at Wheaton College, where he researches and teaches on the intersections race, politics, and popular culture.