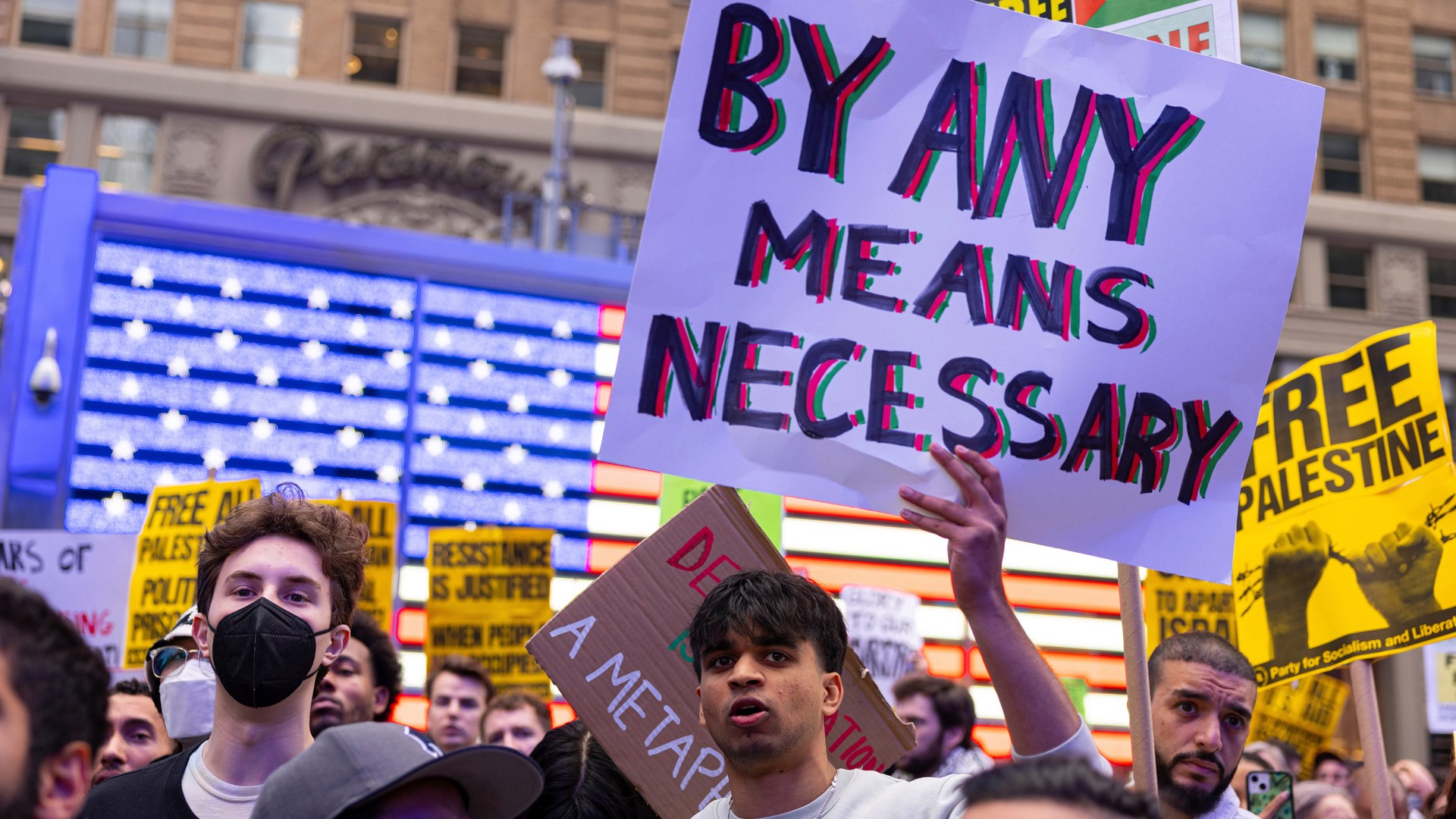

One day after Hamas’s Simchat Torah massacres in Israel, crowds gathered at a rally in Times Square promoted by the Democratic Socialists of America. “Our resistance stormed illegal settlements,” shouted one speaker, “and paraglided across colonial borders.” The crowd responded with rousing cheers.

It was an unapologetic celebration of the terrorists’ multi-front assault on Israeli cities, kibbutzim (progressive, communitarian farming villages), and an outdoor music festival. Hamas members have murdered more than 1,400 Israelis, raped, tortured, and injured thousands, and kidnapped around 200 more. Most of the victims were civilians, and many were children, the elderly, or infants. The vast majority were Jews.

The Times Square gathering was not an isolated case of pro-Hamas activism. Pro-Hamas demonstrations were held by the Chicago chapter of Black Lives Matter and Students for Justice in Palestine at California State University in Long Beach and the University of Louisville, each of which included images of paragliders in their promotional materials—a reference not to the Palestinian cause generally but to this specific Hamas attack on thousands of Israeli innocents.

The parent organization for those campus groups called the initial Hamas assault “a historic win for Palestinian resistance,” encouraging its members not merely to rally but to consider “armed confrontation with the oppressors.”

This war is still in its early days. It may be difficult to parse truth from lies and understand exactly why this kind of activism—which is misleadingly portrayed by its supporters as defense of the oppressed—is wrong. But we’ll have a clearer moral vision if we know the dark history this moment evokes.

We might wonder how the conscience can be warped to such a degree that it justifies or even celebrates such horrific violence. Being generous, I think the apparent power differential between Israelis and Palestinians shapes some of this response. No doubt (as Jewish journalist Bari Weiss chronicled last week), an incoherent ideology on campuses accounts for a significant degree of it as well. But we cannot ignore another subtler, more universal reason behind at least some of these responses: antisemitism.

There’s a sense in which antisemitism is as old as the Exodus, when the Israelites were singled out for slavery by Pharaoh (Ex. 1:9–10) and later, eradication by the Amalekites (Ex. 17:8–9). Hatred of Jews for being Jewish—for refusing to assimilate—is at the center of the book of Esther and remained prevalent under Assyrian and Roman rule. That same antisemitism was a factor, too, when the Romans sacked Jerusalem after a failed Jewish revolt in A.D. 70, sending Jews scattering out of Judea and across the Middle East, Africa, Russia, and Europe.

Through the centuries, Jews have continued to resist assimilation, maintaining and developing their distinct religious practices, language, and customs to this very day. As author Walker Percy once described it, the resilience of the Jewish people is a kind of historical miracle:

When one meets a Jew in New York or New Orleans or Paris or Melbourne, it is remarkable that no one considers the event remarkable. What are they doing here? But it is even more remarkable to wonder, if there are Jews here, why are there not Hittites here? Where are the Hittites? Show me one Hittite in New York City.

But that same resilience and resistance to assimilation continues to be the subject of distrust and hate—more of that ancient antisemitism.

In some ways, this isn’t surprising. As biologists have pointed out, we’re hardwired to feel anxiety about strangers because what makes them different—their language and social habits—triggers a warning in our brains, telling us we may be in competition with them for scarce resources.

But as Christians, we’re challenged to resist that impulse. A biblical admonition running through both Testaments calls us to love our neighbors and to care for sojourners and strangers (e.g., Deut. 1:16, Matt. 25:35). That this runs counter to our (fallen) human nature is evident in all the reasons Christians have manufactured to avoid loving strangers and aliens. Unfortunately, our historic treatment of the Jewish people is a case in point.

Christianity was primarily established by Jewish men and women who recognized a Jewish man as the Son of God. They read from Jewish holy books, and many continued to observe Jewish religious practices.

And yet, by the fourth century, the Jewish origins of Christianity were eclipsed by the contempt of church leaders like Ambrose of Milan, who called Jews “the odious assassins of Christ.” Christians should “never cease” seeking vengeance against the Jewish people, Ambrose said, going so far as to suggest that “God always hated the Jews. It is essential that all Christians hate them.”

All of these claims are antisemitic lies. They are also anti-Christ. The entire Old Testament is about God’s love for Israel as a called-out tribe in a fallen world, and Paul makes clear in Romans 9 that God’s love for Israel is unbroken—even as a “new Israel” is born in Christ.

The allegation that Jews “assassinated” Jesus also runs directly counter to the words of Christ, who said, “No one can take my life from me. I sacrifice it voluntarily. For I have the authority to lay it down when I want to and also to take it up again. For this is what my Father has commanded” (John 10:18, NLT). To say that Jews “murdered” Jesus is to call Jesus a liar.

But lies are seductive, particularly when they serve to alleviate anxiety or fear. The trope that “Jews murdered Jesus” took hold and has endured for centuries, serving as the justification for hostility to Jewish neighbors. In times of social upheaval throughout history, Jews have regularly been offered up as a scapegoat, blamed for everything from political instability to the Black Death.

In the 19th century, the lens for understanding historical events shifted from the Christian story to new ideas like Darwinism and the human-driven progress of history (something I recently wrote about for CT). But this didn’t decrease antisemitism; it merely shifted its shape. Instead of a historical, Christian inflection, Western antisemitism came to have a “scientific” feel.

The new rhetoric framed Jews as an alien race competing with and stealing from other nations. The “Jewish question” (as it came to be known) was the collective anxiety of European nations that didn’t want to offer a place for Jews as equal citizens.

This rhetoric intensified in the 20th century, with Nazis building on centuries of antisemitic history to frame the Jews as a “disease” and “vermin.” It’s awful but critical to note that as deep and vile as Nazi antisemitism was, the near-universal response of the countries Nazi Germany conquered or allied with—such as Poland, France, and Italy—was collaboration in their treatment of Jews.

In many of these places, Jews were rounded up by local officials, robbed of their possessions and land, forced into ghettos, and interned until they could be packed into trains and sent to death camps. For the Nazis, this was the “Final Solution to the Jewish Question.”

This week, as we’ve seen images of unimaginable horror in Israel—Jews tortured and burned alive, parents forced to watch the deaths of their children—that history is as relevant as ever. Israel exists in part to prevent exactly these horrors. The fact that they could happen again and that some in the West could respond with malaise or celebration is a sign of profound moral decay.

Our language in this moment matters. Before Nazi propagandists called Jews “vermin” to be exterminated, they were called aliens and made stateless—denied a place in the world. We must understand that when pro-Hamas protestors chant, “From the river to the sea, Palestine will be free,” they are not simply championing ordinary Palestinians’ plight. They are calling for the eradication of the Jewish state and, implicitly, violence toward Israeli Jews. And when Hamas’s ideological allies call Israeli citizens living in 100-year-old kibbutzim “colonizers” or “white settlers,” they imply that Jews are aliens with no rightful historic ties to the land. It’s the same alienating antisemitism as ever.

I confess, the iconography of the paragliders has disturbed me most of all. This was the method used to assault (among other places) the music festival where more than 260 young Israelis—mostly Jews—were killed while gathering to celebrate the cause of peace. They were slaughtered in open fields. Women were raped next to the dead bodies of their friends and abducted into Gaza to await horrors unknown. We should associate the paragliders with these crimes just like we link Nazi to smoke-billowing crematoria, mass graves, and bodies stacked like cord wood. Wielding a protest sign with a paraglider is like waving around a swastika.

To be horrified by the slaughter of Israeli innocents doesn’t require denying the suffering of the Palestinian people. And caring for Palestinian innocents doesn’t require being cold or numb to the horrors of antisemitism and Hamas. We can condemn Hamas while demanding accountability from Israeli leaders who have fomented violence, elevated right-wing extremists, and excused violations of international law. Indeed, Christians should be marked by our willingness to oppose all injustice and to care for Israeli and Palestinian victims alike.

And while that includes understanding that Palestinians have suffered great injustices from the government of Israel—as well as neighboring states of Egypt, Jordan, Iran, Lebanon, Syria, and Saudi Arabia, as well as Hamas and the Palestinian Authority itself—it must also include active rejection of antisemitism.

As a Jewish friend said to me shortly after the attacks, “We all know what’s coming. People are horrified today. Tomorrow, they’ll do what people have done for centuries. They’ll blame the Jews. It’s just a matter of time.”

That effort has already begun. I hope and pray that Christians can do our part in resisting it.

Mike Cosper is the senior director of podcasts at Christianity Today.