When churchgoers show up to their church’s worship service, they’re often hoping to have a guest with them.

A Lifeway Research study of US Protestant churchgoers finds 3 in 5 (60%) say they have extended at least one invitation in the past six months for someone to attend their church, including 19 percent who have made one invitation, 21 percent with two invitations and 20 percent with three or more invitations.

A third of churchgoers say they haven’t invited anyone to a worship service at their church in the past six months, while 7 percent say they aren’t sure how many invitations they’ve made.

“Churchgoers were not asked the typical net promoter score question of whether they recommend their church. They were asked if they’ve actually invited someone in the last six months,” said Scott McConnell, executive director of Lifeway Research. “For most churchgoers, invitations are not just an aspiration but a current practice.”

Extending invites

Compared to a similar Lifeway Research study six years ago, a similar percentage of churchgoers say they haven’t invited anyone recently—33 percent now versus 29 percent in 2017. Fewer churchgoers, however, are making three or more invitations. In 2017, 1 in 4 said they’d extended at least three invitations for someone to visit their church in the previous six months. Currently, 20 percent say the same.

“It’s not surprising the proportion of churchgoers extending invites is not growing, since the proactive nature of inviting people to church is counter-cultural,” said McConnell. “People in America are not being more relational, but an invitation to church is an invitation to join you in activities you enjoy, a message that brings you hope, and relationships with you and others.”

Some churchgoers are more likely to invite guests than others. Unsurprisingly, those who attend more often are more likely to extend invitations. Churchgoers who attend four times a month or more (27%) are more likely than those who attend less often (11%) to say they’ve made three or more invitations in the past six months.

For those who believe psychology is an enemy of the faith, Steve Arterburn is target number one. As cofounder of New Life Clinics, which absorbed the Minirth-Meier organization in 1984, Arterburn oversees 85 clinics in North America. New Life is the largest Christian provider of psychiatric and psychological services, offering both inpatient and outpatient care. Because of New Life and Minirth-Meier, evangelicals are much more comfortable calling a therapist for help than we were a generation ago.Despite being the author of 25 books dealing mostly with psychological issues and being the host of a national daily radio program dealing with people’s problems, Arterburn himself is not a psychologist but a licensed minister. Still, he has taken on the mantle as the most visible apologist for psychology among evangelical Christians.How did your interest in psychology and counseling develop?

For those who believe psychology is an enemy of the faith, Steve Arterburn is target number one. As cofounder of New Life Clinics, which absorbed the Minirth-Meier organization in 1984, Arterburn oversees 85 clinics in North America. New Life is the largest Christian provider of psychiatric and psychological services, offering both inpatient and outpatient care. Because of New Life and Minirth-Meier, evangelicals are much more comfortable calling a therapist for help than we were a generation ago.Despite being the author of 25 books dealing mostly with psychological issues and being the host of a national daily radio program dealing with people’s problems, Arterburn himself is not a psychologist but a licensed minister. Still, he has taken on the mantle as the most visible apologist for psychology among evangelical Christians.How did your interest in psychology and counseling develop?An early hero of mine was Gertrude Behanna. When I was 12, my father gave me one of her recordings. In it she talked about how she had been very wealthy, lived in the Waldorf Astoria, and eventually became an alcoholic. Later, while recovering from her alcoholism, she opened up her mansions for other alcoholics to live in. She said something that never left me: “Once I began to recover I no longer looked down on people; but then I had the final battle that I had to fight, and that was looking down on people who looked down on people.” I thought that that was such a wonderful statement of truth, that she was going deep. I had been raised around a lot of people who never went that deep into their own motives, their own character defects.Another formative experience was meeting a recovering alcoholic during a seminar on recovery groups at Southwestern Seminary. That led me to work at an alcohol- and drug-treatment center in Fort Worth. So I got trained in addiction and really fell in love with working with addicts. I loved working with them because of their lack of pretense. When an old redneck Texas cowboy came in with puke all over him and just completely out of his mind, it was very difficult for him to put on a facade the next morning. I had lived all my life around people in the church who acted like their act was together, so I found that very refreshing.Why are recovery groups effective in battling pretense?

Because in an AA group there is someone there, someone who’s been around, to tell somebody else to sit down and shut up when they become inappropriate. In church, to tell somebody, “I’m not going to put up with this superficiality anymore” wouldn’t be considered “Christian”; and so in being nice to people, we let them be superficial.Let me give you a personal example. When my wife and I got married, the sexual intimacy of our marriage wasn’t working. We were involved in a support group of four other couples who were older than us, but after one year we began to feel it was a waste of our time to attend. One week my wife said to me, “Next week we’re either going to talk about our problem or we’re not going to be involved with this group.”The next week she did, explaining that you could count the times we had attempted sexual intimacy on one hand. At the time, we didn’t know that thousands of couples experience this in their twentieth year of marriage, much less their first. We just wanted help and felt these older couples could give us come insight. But their only response was to finish off the evening with a polite “Oh, we’re so concerned, and we want to pray for you.”As it turned out, my wife’s authenticity was such a threat that they never came back, and the group ended. Something that could have had a wonderful impact on our lives and could have been an invitation for the others to open up became a horrible experience. Because of the humiliation and rejection we felt, my wife and I didn’t deal with our problem for another year.Seen theologically, this kind of posturing is idolatry—worshipping polished, unblemished images we have created of ourselves for others to see and adore.What prevents us from sharing our problems more openly at church?

Just look at what invitation to conversion we use: “Come to Jesus, and your life is going to be wonderful. It’s going to be great, fantastic. All these problems are going to go away.” There’s some truth to that, but when you hear Dietrich Bonhoeffer say, “When Christ calls a man, he bids him come and die,” that’s the reality that I’ve seen in the Christian faith.I have problems now I would never have had if I hadn’t accepted Christ. There’s guilt that I’ve experienced that I would never even have thought twice about. We have to be realistic with people and tell them that when you come to Jesus, there is a new purpose and a fulfillment, but the struggle is going to continue. We have so many lukewarm Christians or people who turn away from the faith because they’ve been promised this ease.I was in Hawaii doing a conference for pastors. I’m very self-disclosing in everything that I do, and I shared my testimony about how I had paid for an abortion when I was younger, had lived a promiscuous lifestyle, and had reaped the consequences of my actions—describing what happens in a life when you are in control versus God being in control. Afterwards, a minister of a very large congregation told me, “I can never confess to any struggle unless I’ve already experienced victory over the struggle.” Congregations and pastors need to overcome such false ideals. Those that do will strike a blow against the pretentiousness we’re talking about here.I think that’s part of the appeal of pastors like Willow Creek’s Bill Hybels or your pastor at Saddle Back, Rick Warren. They seem to share their struggles openly and appropriately.

Definitely. When someone says to Rick, “I really don’t know if I love my wife,” he responds, “Really! I used to hate my wife. You’re in much better shape than we were!” Then he talks about the struggles they had. That’s inviting to people.Churches need to allow pastors to have problems. History shows that when a church doesn’t allow a pastor to have little problems, many times those pastors go out and get really big ones.Why do some churches oppose Christian psychology?

Let me say first that I would agree with much of the criticism leveled against Christian psychology 20 years ago. There were many calling themselves Christian psychologists, but there was nothing Christian about what they did. They just happened to go to church on Sunday—and some of them weren’t even Christians.But today it’s a totally different picture. Over the past 15 years Christians have begun to take psychology back. You’ve got more marriage and family counselors coming out of Christian colleges than you do from secular colleges. They have a biblical spiritual foundation, which is only right because real psychology is biblical. Psychology means the study of the soul. And while there are ideas within the broader practice that are false, those don’t negate the things that are true.What makes the Christian therapeutic community stand out today from much of secular counseling is its goal: not to help people feel good or cope, but to come to the end of themselves. The goal is not to help people get into themselves, but out of themselves, and to move beyond their problems so they can go on the heal others.What battles have you had in getting churches to work with New Life?

One of my great experiences was with a pastor who asked to meet with me. He told me, “I used to preach against you and against psychology. And I sure preached against anybody taking medication. Then I ended up with a depression so debilitating I could not get out of bed. I languished there for about a month.” Finally his wife convinced him that he had to get help. The church board was going to fire him, and he went to see a Christian psychiatrist who gave him medication. And he said, “Now the thing that I used to preach against is the thing that has set me free to preach.”Something else happened in the process. He discovered that not only did medication not separate him from God, it allowed him to know God in a more real way. He’d always had a thinking problem—adult attention deficit disorder. He just couldn’t focus and concentrate. But once he got on medication for the depression, it helped clear up his thinking, and he was able to study the Bible in a deeper and richer way.So he came and said he was sorry for all the years that he had preached against this.Now I’ll tell you the most dramatic horror story in our area, in Orange County. There was a young man, Michael Pacewitz, who was a paranoid schizophrenic released from a mental institution at the age of 16. He was on heavy medication. A local church took him in, and he did errands around the church. He even did some babysitting. It was a wonderful story of a very severely mentally ill man finding healing and acceptance in the church community.He became a Christian about a year after going to that church. And the pastor said to him, “Michael, now that you’ve accepted Christ, you’re a new creature, and you no longer need medication because you’re a new creature in Christ.” Michael stopped taking the medication.The Orange County Register interviewed him from a jail cell after he had plunged a knife through the heart of a little girl. They interviewed the pastor, and he said, of course, “I will never, ever recommend that a person stop taking medication.”The fact is, psychology has given us tremendous insights into many human problems. Christians, of all people and for Christ’s sake, should be the first to recognize and use these insights for the healing of others.Copyright © 1998 Christianity Today. Click for reprint information.

Those under 50 are more likely to extend invitations than older congregants. Almost a third of those 50 to 64 years old (32%) and nearly half of churchgoers 65 and older (46%) say they have not invited anyone in the past six months. Those 35 to 49 (29%) are most likely to have offered at least three invitations recently.

African American churchgoers are among the most likely to say they’ve extended either two church invitations (28%) or three or more (25%). White churchgoers (36%) are more likely than African Americans (26%) and Hispanics (18%) to say they did not invite anyone in the past six months.

Baptists (27%) and those attending Restorationist Movement churches (21%) are more likely than those at Presbyterian/Reformed congregations (9%) to say they’ve invited at least three individuals or families. Lutherans (52%) are among the most likely to say they haven’t invited anyone.

Churchgoers with evangelical beliefs, which include believing it is very important to encourage non-Christians to trust Jesus Christ as their Savior, are more likely than non-evangelicals to invite others to church. Almost a quarter of evangelicals by belief (24%) say they’ve extended three or more invitations, compared to 15 percent of those without such beliefs.

Invitation limitations

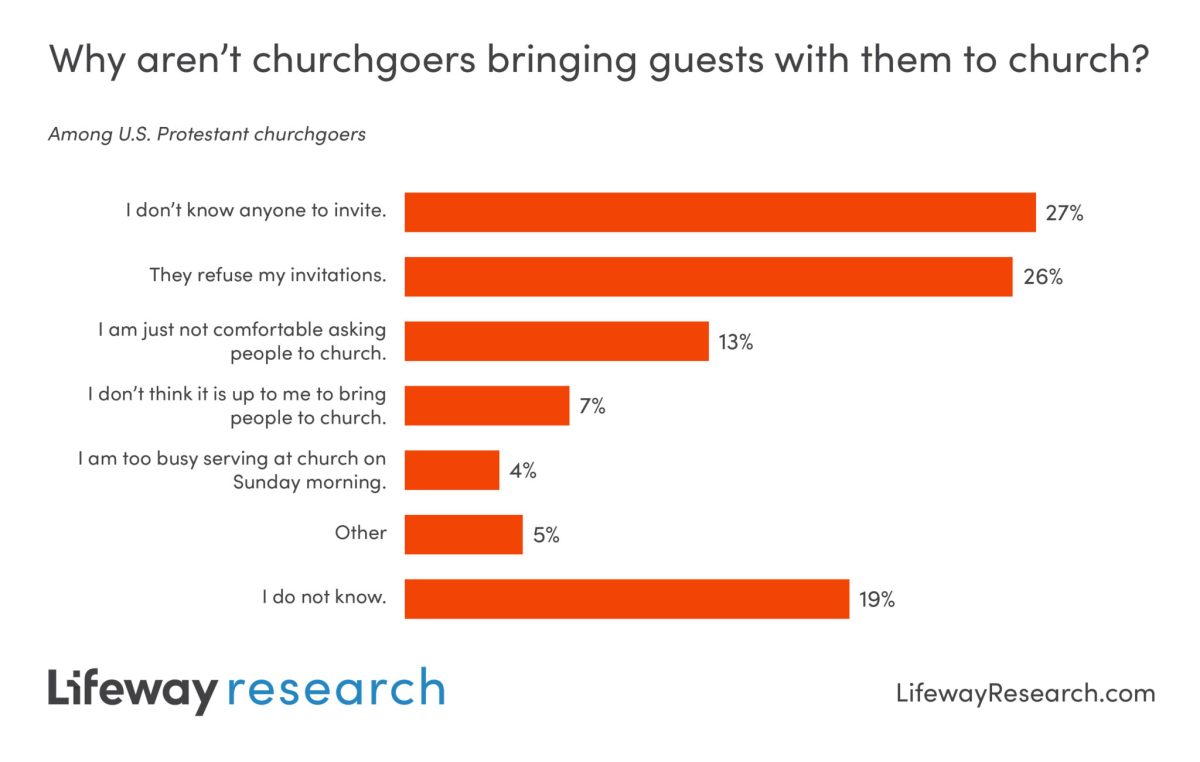

When asked why they don’t bring guests more often, churchgoers point to several reasons. Around a quarter say they don’t know anyone to invite (27%) or those they invite refuse their invitations (26%).

Another 13 percent say they’re just not comfortable asking people to church, while 7 percent say they don’t think it’s up to them to bring people to church. Few (4%) say they’re too busy serving on Sunday morning.

Additionally, 19 percent say they don’t know why they don’t bring guests to church more often, and 5 percent say it’s another unspecified reason.

“It can be easy for churchgoers to have their own relationship needs met at church and not know anyone else to invite,” said McConnell. “It takes intentionality to be meeting new people in your community to have opportunities to invite them.”

When Nicky Gumbel began teaching the Alpha course in 1990, originally intended for new Christians, the Oxford educated barrister-turned-Anglican-priest soon discovered that many students were not Christians at all. They were, however, spiritually curious.After mulling over how to meet their needs, Gumbel and leaders from his parish, Holy Trinity Brompton, where the Alpha course began in 1977, restructured and reworked the course curriculum so that non-Christians would be able to understand the basics of Christianity.The revised course, as spelled out in Gumbel’s book Questions of Life, does not begin with well-known theological categories and issues of doctrine. Its starting point is instead the experience of many nonbelievers that Christianity seems “boring, untrue, and irrelevant.”The impact on attendance was explosive. “Every talk is aimed at somebody who is outside the church,” Gumbel says. “When we did that, we found that the numbers just rocketed.” Holy Trinity’s most recently concluded Alpha course drew 1,200 people, one of the largest groups ever, for the course’s celebration dinner, an event that functions both as course climax and kickoff for the next round of instruction.Alpha’s full impact is no longer focused solely at Holy Trinity Brompton, a Church of England parish that is one of the most influential evangelical and charismatic congregations in Europe. Starting in 1993, Gumbel and Holy Trinity leaders released Alpha materials to churches throughout the United Kingdom first, and then to the rest of Europe, North America, and worldwide.Global growth rates for the number of Alpha courses and attendees initially stunned Gumbel. “It was an amazement to us that it would work in any other church outside our own,” he says. In 1991, four Alpha courses drew 600 people. In 1997, an estimated 500,000 attended courses around the world. Gumbel and Alistair Hanna, a former corporate consultant and now head of Alpha North America, believe that by the year 2001 some 50,000 Alpha courses could be held yearly in the United States and Canada.“I like to say that the biggest denomination in America is the unchurched,” Hanna says. “There are 86 million of them. We don’t need to poach from each other. We can actually go out and find people who don’t go to church at all.” Hanna envisions an Alpha course for every 5,000 residents of North America. But he says, “We won’t be as good as McDonald’s and say we’ve got an Alpha course within four minutes of you.” An infectious enthusiasm, entrepreneurial spirit, and a bold plan for growth are all trademarks among Alpha’s top leaders.But not everyone is cheering Alpha onward. Some church leaders have found Alpha teachings too charismatic, too experience-driven, and too negative about traditional churches. Martyn Percy, director of the Lincoln Theological Institute for the Study of Religion and Society of the University of Sheffield, England, has commented about Alpha that it is “a package rather than a pilgrimage.” In a recent essay, he said, “It is a confident but narrow expression of Christianity, which stresses the personal experience of the Spirit over the Spirit in the church.”The ten-week Alpha course bears some theological similarity to the bestsellers Mere Christianity, by C. S. Lewis, and Basic Christianity, by John Stott. But Alpha is significantly different, and it is its distinctives that have drawn criticism. For example, there is a strong emphasis on class attendees inviting the Holy Spirit to fill them. Gumbel says individuals are not required to speak in tongues, but it is very common for Alpha attendees to do so.CHURCH-BASED EVANGELISM: Since Alpha is designed to be run in local churches, the program makes extensive use of promotional endorsements from prominent church leaders as well as emotional testimonials on how Alpha has transformed lives.The Alpha program calls for congregations to rethink their approach to evangelism. Instead of offering church-based community events or services that might expose nonbelievers to a congregation, Alpha instructs leaders on how to use an invite-your-friends model to stimulate interest in Christian doctrine.“We don’t try to get people who are not interested,” Gumbel says. “The reason they have an interest is not because they have an interest suddenly in Christianity, but because of what happened to their friend on the previous course.”The Alpha system at first blush seems overly simplistic. The acronym stands for: A—Anyone interested in finding out more about the Christian faith; L—Learning and Laughter; P—Pasta (eating together gives people the chance to know each other); H—Helping one another (small groups are used for discussion of issues raised during the lectures); A—Ask anything. No question is seen as too simple or too hostile.However, Alpha, in the hands of skilled church leaders, has succeeded in many cases in turning faithful churchgoers from an inward focus on church work to an outward focus on evangelistic outreach through relationships, networking, and invitations to Alpha events. In Gumbel’s words, Alpha stimulates a “virtuous circle” that spreads outward, allowing churches regularly to break into new networks of unchurched, unevangelized people.During the past six months, Alpha North America has held leadership-training conferences in Vancouver, British Columbia; and Overland Park, Kansas; among other places. In 1998, similar two-day events are scheduled at other venues around the United States. (Information is available from 1-888-949-2574).Many people first experience the Alpha course as a series of videotapes featuring the telegenic Gumbel. But for a good half of the 450 people who attended an Alpha leaders conference in the suburbs of Kansas City in January, their first glimpse of the self-effacing, humorous speaker was in person.The two-day Alpha conference trains people to run an Alpha course. In some ways the conference resembled Alpha’s signature Holy Spirit weekend, featuring contemporary worship music; back-to-back talks by “the two Nickys”—Gumbel and his lifelong friend, Nicky Lee, also an Anglican priest; dramatic testimonies by Alpha converts; and charismatic prayer sessions during which some people speak in tongues or fall prostrate on a carpeted floor.Gumbel described Alpha’s approach as a conscious effort to touch both minds and hearts with the gospel. Each plenary session included testimonies from people who became Christians or had their faith deepened through involvement with Alpha.Keith Prestridge of Overland Park gave a brief talk on the first evening, striding toward the platform in a black leather jacket. Prestridge talked about leading a “punk rock, acid jazz” band known as the Screaming Beagles. Prestridge followed the ultraviolent philosophy of a character in Anthony Burgess’s novel A Clockwork Orange until he dropped in one morning during worship at a Vineyard Fellowship service. Prestridge offered a pugilist’s description of Alpha’s Holy Spirit weekend: “They laid hands on me, and I knew release, you know? I know those of you who have felt the Spirit know what it’s like. It’s like being in a good fight and suddenly being knocked out.”The Kansas Alpha conference attracted a cross-denominational group, including seven members of the Salvation Army. Maj. Ron Gorton of the Salvation Army in Kansas City, Kansas, says he became acquainted with Alpha because Salvationists in England have operated courses.Gorton says he and other Salvationists are discussing whether the Alpha course will meet their needs as they make changes in the Army’s substance-abuse recovery program. “The things that God is teaching through this course are very similar to what he has been teaching us through our drug-and-alcohol program,” Gorton says. “God has taught us that we need to break down this barrier of ‘us and you.’ “Most testimonies at the Alpha conference focused on experiences at its Holy Spirit weekends. Hairdresser Mark Walker of Rogersville, Missouri, spoke about being delivered from two decades of drug addiction.“After 21 years of drug abuse, three rehabilitation centers, two mental institutions, and two passes through jail, I decided I needed to change my life,” he says. Walker missed a few of the first Alpha sessions, but then he went on the weekend retreat. “Late in the evening I laid in the back of my pickup truck and asked God to fill me with the Holy Spirit,” he says.BAPTISTS ADJUST ALPHA: Alpha courses have been held in about 50 countries. Although many have been held in Anglican, Vineyard, or independent charismatic churches, Alpha is gaining a foothold internationally among Roman Catholics, Baptists, and other faith groups.One of the most expensive neighborhoods in Canada is the west side of Vancouver, British Columbia. Vancouver itself is one of the most secular cities in North America, and church growth, when it happens, is slow.But Sally Start, a member of Vancouver’s Dunbar Heights Baptist Church, began inviting a handful of her neighbors to join her in watching the Alpha videos a couple of years ago. Two of those neighbors have since joined the church and are now helping her run Alpha, which has since moved into the church with the leadership’s blessing. About 20 new people have expressed interest in taking the next Alpha course. That is a hefty proportion for a church of only 50 people.One of Dunbar Heights’ newer members is 43-year-old Don Macdonald, an accountant who, barely a year ago, was a self-described atheist. His wife had been a long-time member of the church.“Sally challenged me” to take the course, he says. By the time he finished, “I just couldn’t believe there wasn’t a God.” From there, salvation through Christ resulted. “My heart finally convinced me.”“Our experience has been that none of [the participants], by the time they finish the course, are able to say anything other than Christianity is true,” says Start. Not all of them make Christian commitments within the course, and of those who do, not all stay at Dunbar Heights. Some find that church too conservative and go elsewhere. “We’re making a difference from a kingdom perspective, and that’s what we keep focusing on,” Start says.Alpha’s openness to questions allows people to experience learning about the Christian faith in a way that is not threatening.Some have had “toxic” religious experiences in the past, says Start. They need to be able to say what they think and be accepted for who they are. Others have a “refreshing navet” about the Christian faith. They do not carry the same “inhibitions” as people who have been raised in the church.One of the young women helping to lead the Alpha course was having trouble conceiving. A bout with cancer and surgery made it less likely that she would become pregnant. The Alpha group prayed for her, and just before Christmas she gave birth to a baby boy. Start says, “I’m not sure if outside Alpha we would have prayed.”Start and her pastor, Darcy Van Horn, are cautious about Alpha’s teaching on the Holy Spirit. “There seems to be more of a stress on the gift of tongues than I think is biblically warranted,” says Van Horn.“I’m a little leery of people who are not yet saved being pressed to be filled with the Spirit.” Repentance is necessary before that should take place, he says. Van Horn is not bothered enough by the Holy Spirit teaching to dismiss Alpha altogether, however. “We have at times worked around that a little bit,” he admits. Other pastors have done the same thing, despite Gumbel’s emphasis on the importance of not modifying the curriculum.In a society where faith is viewed as a private matter, Van Horn is pleased to provide a means for Christians to express what they believe. “One of my goals is to see people in the church equipped to share the gospel where they are,” he says. “Not everyone is comfortable with that. Alpha gives them a practical way to fulfill their responsibility to evangelize.”EXPERIENCE OVER REASON? The Alpha approach has been faulted for pushing an experience-driven approach to evangelism that sidesteps intellectual difficulties. Yet Peter Horton, Rick Richardson, and a team from the interdenominational Church of the Resurrection in Glen Ellyn, Illinois, have found Alpha useful in reaching Generation X, young adults in their twenties and early thirties.“Anything you do with Generation X needs to be relational,” says Horton. “You have to show them that Christianity applies to things that they are struggling with and is relevant for them.”The Alpha structure is built to encourage relationships. “You bring your friends to Alpha and you start with a meal, which builds relationships,” Horton says. Paula Karrasch, a recent college graduate, took part in Alpha a year ago. Karrasch says, “The meal forced me to talk to people. I couldn’t hide. I had to relate to people.”The participants in the course are also divided into small groups from the beginning and attend a weekend get-together. “The purpose of the small group is to build community and relationship,” says Horton. “It’s meant to be a place where people can be open and ask questions.”Horton stresses the importance of authenticity and relevance in relating to Generation X. “Our personal stories of our relationships with Jesus are really important in showing them who Jesus is. I’m myself, being authentic and real. I think Generation X really wants to hear my story so they can see if it really works for me.”“Rick told a lot of stories from his own life,” says Karrasch. “I could see he wasn’t this perfect, crystal clear Christian.” They also watched a Mr. Bean video in which British comedian Rowan Atkinson falls asleep repeatedly throughout an Anglican church service. “It related to me as I didn’t know what was happening in church. I could identify with Mr. Bean.”Alpha uses both apologetics and personal stories to communicate its evangelistic message. “Generally, Generation Xers are not interested in apologetics,” says Horton, “but are very interested in personal stories or narrative.” Horton believes that the stories bypass the “cynicism of Generation X.”Horton says, “It’s not proof that they want, but experience. Typically, they’re not asking me to prove that Christ died. They’re more interested in what impact Christ will have on their lives.“One of the principles of Alpha is that evangelism involves the whole person, the head, the heart, and the will,” says Horton. Accordingly, the Alpha course allows participants to encounter God in many different ways. “It’s an opportunity for them to explore Christianity and see whether it can address their needs.”QUESTIONS OF GUMBEL: More church leaders and scholars have questioned the Alpha program as it has gained a higher profile, and many of the criticisms have been focused on Alpha audio- and videocassettes. Gumbel says the definitive Alpha curriculum is his book Questions of Life, and all ten Alpha teachings have been further revised and revideotaped.Nevertheless, a lengthy critique of Questions of Life has been published in the January 1998 Episcopal Evangelical Journal. In his review, Roger Steer, a British author, faults Gumbel for downplaying the sacrificial nature of Christian living, for selectively quoting Scripture, and for portraying established churches as “dreary and uninspiring.”Steer in part focuses on Gumbel’s selective scriptural quotation concerning speaking in tongues. In 1 Corinthians 14:5, Paul says, “I would like everyone of you to speak in tongues, but I would rather have you prophesy” (NIV). However, in Questions of Life, Gumbel says, “Not every Christian speaks in tongues. Yet Paul says, ‘I would like everyone of you to speak in tongues,’ suggesting that it is not only for a special class of Christians. It is open to all Christians. … If you would like to receive it, there is no reason why you should not.” Steer asserts that Gumbel is wrongly suggesting that it is normative for speaking in tongues to accompany infilling of the Holy Spirit.During a lengthy interview, Gumbel discussed Alpha criticism, saying, “We haven’t got everything perfect. Alpha is alive. It’s not fixed. That’s why we revideoed [the Alpha lectures], because we were trying to respond to criticisms.” He says when there is another printing of Questions of Life he usually makes editorial changes, based on suggestions from church leaders.Gumbel says Alpha materials avoid using the word charismatic because “we don’t regard it as charismatic; it’s just what we see as Trinitarian.” Some leaders believe Alpha has too much about speaking in tongues, Gumbel says, while others say there is not enough. But Alpha’s aim, he says, is to hold together the theological streams represented by its teaching on the sacraments, justification by faith, and infilling of the Holy Spirit.Because Alpha’s home base has been in the United Kingdom, church leaders there have the most experience with the course program. And to date, their enthusiasm is not flagging.For 1998, they plan the unprecedented initiative of inviting every unchurched person in the United Kingdom to an Alpha course in October. Gumbel says, “There is an Alpha course within striking distance of everyone in the U.K. and within walking distance of most.” The effort has the potential to transform many of the nation’s churches into hothouses for evangelistic outreach. “That’s the vision,” Gumbel says. “We hardly dare even mention it. We’re trying to keep our heads down. The higher the profile the more people are out there trying to knock it.”Meanwhile, Alpha North America’s Alistair Hanna is searching for 5,000 church leaders to attend one of the ten training conferences this year. He says Alpha is not a “magic bullet.”“It’s a lot of work,” Hanna says. “It takes sustained effort and faith. One of the things that quite often happens is after you’ve worked your way through your church, the next [Alpha] could be very small.” Hanna says one pastor had only seven people show up for his third Alpha course. “He realized that this wasn’t going to do anything for anybody if he didn’t get people out, having friends bringing friends.”With reports from Doug LeBlanc, Overland Park, Kansas; Debra Fieguth, Vancouver, British Columbia, Canada; and Mary Cagney, Glen Ellyn, Illinois.Copyright © 1998 Christianity Today. Click for reprint information.

When Nicky Gumbel began teaching the Alpha course in 1990, originally intended for new Christians, the Oxford educated barrister-turned-Anglican-priest soon discovered that many students were not Christians at all. They were, however, spiritually curious.After mulling over how to meet their needs, Gumbel and leaders from his parish, Holy Trinity Brompton, where the Alpha course began in 1977, restructured and reworked the course curriculum so that non-Christians would be able to understand the basics of Christianity.The revised course, as spelled out in Gumbel’s book Questions of Life, does not begin with well-known theological categories and issues of doctrine. Its starting point is instead the experience of many nonbelievers that Christianity seems “boring, untrue, and irrelevant.”The impact on attendance was explosive. “Every talk is aimed at somebody who is outside the church,” Gumbel says. “When we did that, we found that the numbers just rocketed.” Holy Trinity’s most recently concluded Alpha course drew 1,200 people, one of the largest groups ever, for the course’s celebration dinner, an event that functions both as course climax and kickoff for the next round of instruction.Alpha’s full impact is no longer focused solely at Holy Trinity Brompton, a Church of England parish that is one of the most influential evangelical and charismatic congregations in Europe. Starting in 1993, Gumbel and Holy Trinity leaders released Alpha materials to churches throughout the United Kingdom first, and then to the rest of Europe, North America, and worldwide.Global growth rates for the number of Alpha courses and attendees initially stunned Gumbel. “It was an amazement to us that it would work in any other church outside our own,” he says. In 1991, four Alpha courses drew 600 people. In 1997, an estimated 500,000 attended courses around the world. Gumbel and Alistair Hanna, a former corporate consultant and now head of Alpha North America, believe that by the year 2001 some 50,000 Alpha courses could be held yearly in the United States and Canada.“I like to say that the biggest denomination in America is the unchurched,” Hanna says. “There are 86 million of them. We don’t need to poach from each other. We can actually go out and find people who don’t go to church at all.” Hanna envisions an Alpha course for every 5,000 residents of North America. But he says, “We won’t be as good as McDonald’s and say we’ve got an Alpha course within four minutes of you.” An infectious enthusiasm, entrepreneurial spirit, and a bold plan for growth are all trademarks among Alpha’s top leaders.But not everyone is cheering Alpha onward. Some church leaders have found Alpha teachings too charismatic, too experience-driven, and too negative about traditional churches. Martyn Percy, director of the Lincoln Theological Institute for the Study of Religion and Society of the University of Sheffield, England, has commented about Alpha that it is “a package rather than a pilgrimage.” In a recent essay, he said, “It is a confident but narrow expression of Christianity, which stresses the personal experience of the Spirit over the Spirit in the church.”The ten-week Alpha course bears some theological similarity to the bestsellers Mere Christianity, by C. S. Lewis, and Basic Christianity, by John Stott. But Alpha is significantly different, and it is its distinctives that have drawn criticism. For example, there is a strong emphasis on class attendees inviting the Holy Spirit to fill them. Gumbel says individuals are not required to speak in tongues, but it is very common for Alpha attendees to do so.CHURCH-BASED EVANGELISM: Since Alpha is designed to be run in local churches, the program makes extensive use of promotional endorsements from prominent church leaders as well as emotional testimonials on how Alpha has transformed lives.The Alpha program calls for congregations to rethink their approach to evangelism. Instead of offering church-based community events or services that might expose nonbelievers to a congregation, Alpha instructs leaders on how to use an invite-your-friends model to stimulate interest in Christian doctrine.“We don’t try to get people who are not interested,” Gumbel says. “The reason they have an interest is not because they have an interest suddenly in Christianity, but because of what happened to their friend on the previous course.”The Alpha system at first blush seems overly simplistic. The acronym stands for: A—Anyone interested in finding out more about the Christian faith; L—Learning and Laughter; P—Pasta (eating together gives people the chance to know each other); H—Helping one another (small groups are used for discussion of issues raised during the lectures); A—Ask anything. No question is seen as too simple or too hostile.However, Alpha, in the hands of skilled church leaders, has succeeded in many cases in turning faithful churchgoers from an inward focus on church work to an outward focus on evangelistic outreach through relationships, networking, and invitations to Alpha events. In Gumbel’s words, Alpha stimulates a “virtuous circle” that spreads outward, allowing churches regularly to break into new networks of unchurched, unevangelized people.During the past six months, Alpha North America has held leadership-training conferences in Vancouver, British Columbia; and Overland Park, Kansas; among other places. In 1998, similar two-day events are scheduled at other venues around the United States. (Information is available from 1-888-949-2574).Many people first experience the Alpha course as a series of videotapes featuring the telegenic Gumbel. But for a good half of the 450 people who attended an Alpha leaders conference in the suburbs of Kansas City in January, their first glimpse of the self-effacing, humorous speaker was in person.The two-day Alpha conference trains people to run an Alpha course. In some ways the conference resembled Alpha’s signature Holy Spirit weekend, featuring contemporary worship music; back-to-back talks by “the two Nickys”—Gumbel and his lifelong friend, Nicky Lee, also an Anglican priest; dramatic testimonies by Alpha converts; and charismatic prayer sessions during which some people speak in tongues or fall prostrate on a carpeted floor.Gumbel described Alpha’s approach as a conscious effort to touch both minds and hearts with the gospel. Each plenary session included testimonies from people who became Christians or had their faith deepened through involvement with Alpha.Keith Prestridge of Overland Park gave a brief talk on the first evening, striding toward the platform in a black leather jacket. Prestridge talked about leading a “punk rock, acid jazz” band known as the Screaming Beagles. Prestridge followed the ultraviolent philosophy of a character in Anthony Burgess’s novel A Clockwork Orange until he dropped in one morning during worship at a Vineyard Fellowship service. Prestridge offered a pugilist’s description of Alpha’s Holy Spirit weekend: “They laid hands on me, and I knew release, you know? I know those of you who have felt the Spirit know what it’s like. It’s like being in a good fight and suddenly being knocked out.”The Kansas Alpha conference attracted a cross-denominational group, including seven members of the Salvation Army. Maj. Ron Gorton of the Salvation Army in Kansas City, Kansas, says he became acquainted with Alpha because Salvationists in England have operated courses.Gorton says he and other Salvationists are discussing whether the Alpha course will meet their needs as they make changes in the Army’s substance-abuse recovery program. “The things that God is teaching through this course are very similar to what he has been teaching us through our drug-and-alcohol program,” Gorton says. “God has taught us that we need to break down this barrier of ‘us and you.’ “Most testimonies at the Alpha conference focused on experiences at its Holy Spirit weekends. Hairdresser Mark Walker of Rogersville, Missouri, spoke about being delivered from two decades of drug addiction.“After 21 years of drug abuse, three rehabilitation centers, two mental institutions, and two passes through jail, I decided I needed to change my life,” he says. Walker missed a few of the first Alpha sessions, but then he went on the weekend retreat. “Late in the evening I laid in the back of my pickup truck and asked God to fill me with the Holy Spirit,” he says.BAPTISTS ADJUST ALPHA: Alpha courses have been held in about 50 countries. Although many have been held in Anglican, Vineyard, or independent charismatic churches, Alpha is gaining a foothold internationally among Roman Catholics, Baptists, and other faith groups.One of the most expensive neighborhoods in Canada is the west side of Vancouver, British Columbia. Vancouver itself is one of the most secular cities in North America, and church growth, when it happens, is slow.But Sally Start, a member of Vancouver’s Dunbar Heights Baptist Church, began inviting a handful of her neighbors to join her in watching the Alpha videos a couple of years ago. Two of those neighbors have since joined the church and are now helping her run Alpha, which has since moved into the church with the leadership’s blessing. About 20 new people have expressed interest in taking the next Alpha course. That is a hefty proportion for a church of only 50 people.One of Dunbar Heights’ newer members is 43-year-old Don Macdonald, an accountant who, barely a year ago, was a self-described atheist. His wife had been a long-time member of the church.“Sally challenged me” to take the course, he says. By the time he finished, “I just couldn’t believe there wasn’t a God.” From there, salvation through Christ resulted. “My heart finally convinced me.”“Our experience has been that none of [the participants], by the time they finish the course, are able to say anything other than Christianity is true,” says Start. Not all of them make Christian commitments within the course, and of those who do, not all stay at Dunbar Heights. Some find that church too conservative and go elsewhere. “We’re making a difference from a kingdom perspective, and that’s what we keep focusing on,” Start says.Alpha’s openness to questions allows people to experience learning about the Christian faith in a way that is not threatening.Some have had “toxic” religious experiences in the past, says Start. They need to be able to say what they think and be accepted for who they are. Others have a “refreshing navet” about the Christian faith. They do not carry the same “inhibitions” as people who have been raised in the church.One of the young women helping to lead the Alpha course was having trouble conceiving. A bout with cancer and surgery made it less likely that she would become pregnant. The Alpha group prayed for her, and just before Christmas she gave birth to a baby boy. Start says, “I’m not sure if outside Alpha we would have prayed.”Start and her pastor, Darcy Van Horn, are cautious about Alpha’s teaching on the Holy Spirit. “There seems to be more of a stress on the gift of tongues than I think is biblically warranted,” says Van Horn.“I’m a little leery of people who are not yet saved being pressed to be filled with the Spirit.” Repentance is necessary before that should take place, he says. Van Horn is not bothered enough by the Holy Spirit teaching to dismiss Alpha altogether, however. “We have at times worked around that a little bit,” he admits. Other pastors have done the same thing, despite Gumbel’s emphasis on the importance of not modifying the curriculum.In a society where faith is viewed as a private matter, Van Horn is pleased to provide a means for Christians to express what they believe. “One of my goals is to see people in the church equipped to share the gospel where they are,” he says. “Not everyone is comfortable with that. Alpha gives them a practical way to fulfill their responsibility to evangelize.”EXPERIENCE OVER REASON? The Alpha approach has been faulted for pushing an experience-driven approach to evangelism that sidesteps intellectual difficulties. Yet Peter Horton, Rick Richardson, and a team from the interdenominational Church of the Resurrection in Glen Ellyn, Illinois, have found Alpha useful in reaching Generation X, young adults in their twenties and early thirties.“Anything you do with Generation X needs to be relational,” says Horton. “You have to show them that Christianity applies to things that they are struggling with and is relevant for them.”The Alpha structure is built to encourage relationships. “You bring your friends to Alpha and you start with a meal, which builds relationships,” Horton says. Paula Karrasch, a recent college graduate, took part in Alpha a year ago. Karrasch says, “The meal forced me to talk to people. I couldn’t hide. I had to relate to people.”The participants in the course are also divided into small groups from the beginning and attend a weekend get-together. “The purpose of the small group is to build community and relationship,” says Horton. “It’s meant to be a place where people can be open and ask questions.”Horton stresses the importance of authenticity and relevance in relating to Generation X. “Our personal stories of our relationships with Jesus are really important in showing them who Jesus is. I’m myself, being authentic and real. I think Generation X really wants to hear my story so they can see if it really works for me.”“Rick told a lot of stories from his own life,” says Karrasch. “I could see he wasn’t this perfect, crystal clear Christian.” They also watched a Mr. Bean video in which British comedian Rowan Atkinson falls asleep repeatedly throughout an Anglican church service. “It related to me as I didn’t know what was happening in church. I could identify with Mr. Bean.”Alpha uses both apologetics and personal stories to communicate its evangelistic message. “Generally, Generation Xers are not interested in apologetics,” says Horton, “but are very interested in personal stories or narrative.” Horton believes that the stories bypass the “cynicism of Generation X.”Horton says, “It’s not proof that they want, but experience. Typically, they’re not asking me to prove that Christ died. They’re more interested in what impact Christ will have on their lives.“One of the principles of Alpha is that evangelism involves the whole person, the head, the heart, and the will,” says Horton. Accordingly, the Alpha course allows participants to encounter God in many different ways. “It’s an opportunity for them to explore Christianity and see whether it can address their needs.”QUESTIONS OF GUMBEL: More church leaders and scholars have questioned the Alpha program as it has gained a higher profile, and many of the criticisms have been focused on Alpha audio- and videocassettes. Gumbel says the definitive Alpha curriculum is his book Questions of Life, and all ten Alpha teachings have been further revised and revideotaped.Nevertheless, a lengthy critique of Questions of Life has been published in the January 1998 Episcopal Evangelical Journal. In his review, Roger Steer, a British author, faults Gumbel for downplaying the sacrificial nature of Christian living, for selectively quoting Scripture, and for portraying established churches as “dreary and uninspiring.”Steer in part focuses on Gumbel’s selective scriptural quotation concerning speaking in tongues. In 1 Corinthians 14:5, Paul says, “I would like everyone of you to speak in tongues, but I would rather have you prophesy” (NIV). However, in Questions of Life, Gumbel says, “Not every Christian speaks in tongues. Yet Paul says, ‘I would like everyone of you to speak in tongues,’ suggesting that it is not only for a special class of Christians. It is open to all Christians. … If you would like to receive it, there is no reason why you should not.” Steer asserts that Gumbel is wrongly suggesting that it is normative for speaking in tongues to accompany infilling of the Holy Spirit.During a lengthy interview, Gumbel discussed Alpha criticism, saying, “We haven’t got everything perfect. Alpha is alive. It’s not fixed. That’s why we revideoed [the Alpha lectures], because we were trying to respond to criticisms.” He says when there is another printing of Questions of Life he usually makes editorial changes, based on suggestions from church leaders.Gumbel says Alpha materials avoid using the word charismatic because “we don’t regard it as charismatic; it’s just what we see as Trinitarian.” Some leaders believe Alpha has too much about speaking in tongues, Gumbel says, while others say there is not enough. But Alpha’s aim, he says, is to hold together the theological streams represented by its teaching on the sacraments, justification by faith, and infilling of the Holy Spirit.Because Alpha’s home base has been in the United Kingdom, church leaders there have the most experience with the course program. And to date, their enthusiasm is not flagging.For 1998, they plan the unprecedented initiative of inviting every unchurched person in the United Kingdom to an Alpha course in October. Gumbel says, “There is an Alpha course within striking distance of everyone in the U.K. and within walking distance of most.” The effort has the potential to transform many of the nation’s churches into hothouses for evangelistic outreach. “That’s the vision,” Gumbel says. “We hardly dare even mention it. We’re trying to keep our heads down. The higher the profile the more people are out there trying to knock it.”Meanwhile, Alpha North America’s Alistair Hanna is searching for 5,000 church leaders to attend one of the ten training conferences this year. He says Alpha is not a “magic bullet.”“It’s a lot of work,” Hanna says. “It takes sustained effort and faith. One of the things that quite often happens is after you’ve worked your way through your church, the next [Alpha] could be very small.” Hanna says one pastor had only seven people show up for his third Alpha course. “He realized that this wasn’t going to do anything for anybody if he didn’t get people out, having friends bringing friends.”With reports from Doug LeBlanc, Overland Park, Kansas; Debra Fieguth, Vancouver, British Columbia, Canada; and Mary Cagney, Glen Ellyn, Illinois.Copyright © 1998 Christianity Today. Click for reprint information.Compared to 2017, churchgoers today are more likely to say they don’t know anyone to invite (27 percent v. 17%) and those they invited said no (26 percent v. 20%). Current churchgoers are less likely than those in 2017 to say they aren’t sure of the reason they don’t bring guests more often (19% v. 31%) or to point to another unnamed reason (5% v. 15%).

Those who attend most often say the reason they don’t have guests with them more frequently is because their invitations are refused. Those who attend a worship service four times a month or more (31%) are more likely than those who attend one to three times (19%) to say a rejected invitation is the primary reason.

Baptists (33%), as well as those at non-denominational (27%) and Restorationist Movement (24%) churches are more likely than Lutherans (12%) and Presbyterian/Reformed (11%) to say the primary reason they don’t bring guests with them to worship services more often is because the potential guests refuse their invitations.

Methodists (28%), Lutherans (24%) and those at Restorationist Movement churches (19%) are more likely than Baptists (9%) to say they aren’t bringing guests with them because they aren’t comfortable asking people to church. Additionally, Methodists (23%) are among the most likely to say they don’t think it’s up to them to bring people to church.