Photography by Ben Weller for Christianity Today

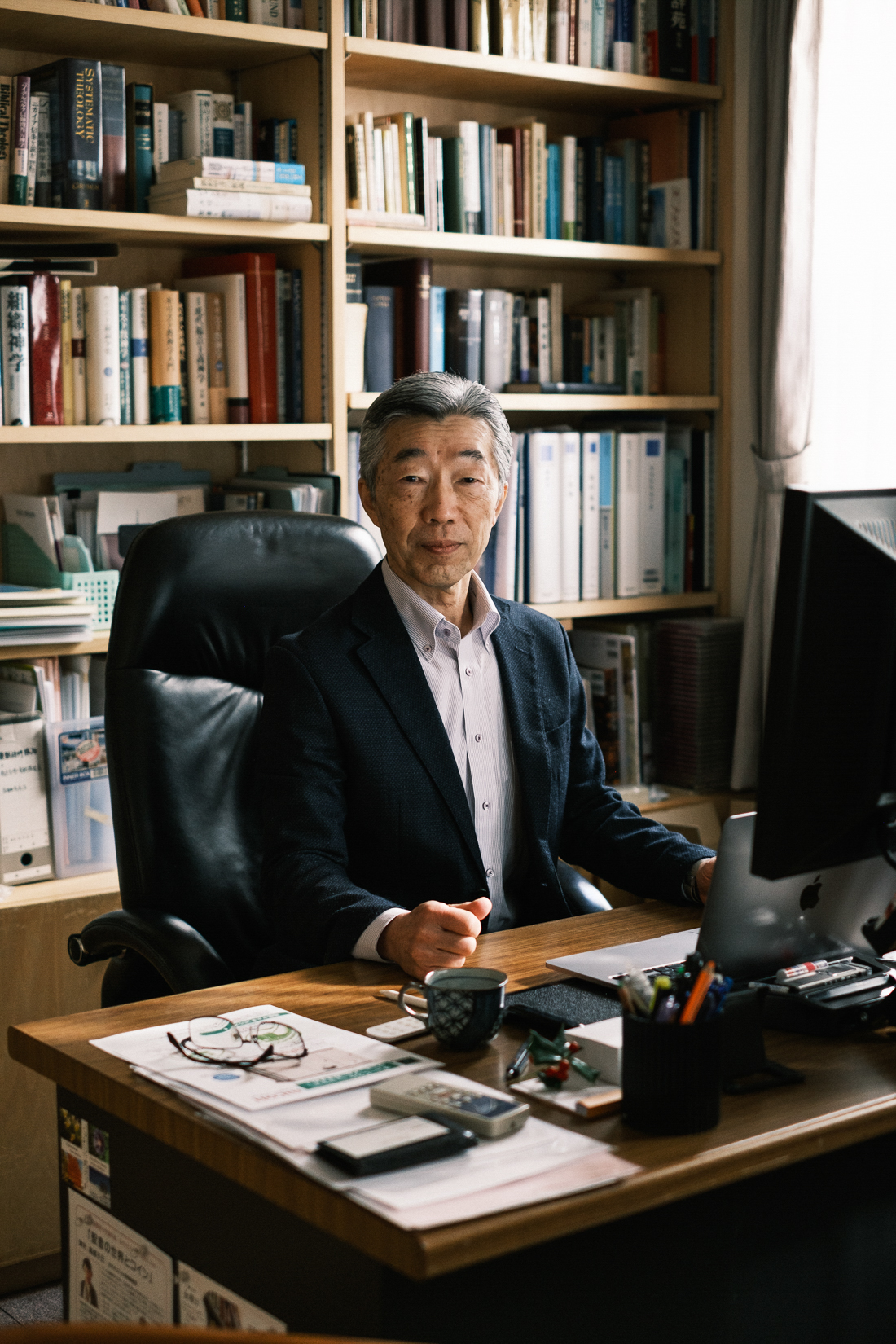

Photography by Ben Weller for Christianity TodayAkasaka Izumi’s office is only slightly larger than a bachelor’s closet. The principal of Japan Bible Seminary has just enough room for a desk, some bookshelves jammed with theology volumes, and a coffee table.

We sipped from dainty cups of dark coffee while Akasaka eyed the clock. We were scheduled to talk with a pastor on Zoom at 2:30 p.m. At 2:31, when the pastor had not appeared, Akasaka began fidgeting.

“Something’s wrong,” he muttered, picking up his cellphone. “I better call.”

“It’s only been one minute,” I pointed out. But he dialed the pastor anyway. “Yes, but you know, we’re Japanese.”

It’s not so much that the Japanese people hate tardiness, I learned, as they hate being inconsiderate. Such civility so impressed the Spanish Jesuit priest Francis Xavier, who led the first Christian mission to Japan in the 16th century, that he urged only the highest quality missionaries be sent to the country. His successor, Cosme de Torres, was equally enamored with Japanese culture. He wrote in a report to Rome, “If I should strive to write all the good qualities and virtues which are found in [the Japanese], I should run out of paper and ink.”

Five hundred years later, the West is still fascinated with all things Japanese. But the country’s culture is a stumbling block when it comes to evangelism, one missionary told me: “Japanese culture is beautiful. It’s near perfect.”

How do you show near-perfect people that they too desperately need the gospel?

Within missions circles, Japan is known as a “missionary graveyard,” a place where the best efforts bear little fruit. The country has one of the world’s largest unreached people groups. The more than 125 million people there have fewer than 10,000 churches, including Catholic and Orthodox ones. Christians account for less than 1 percent of Japan’s population.

According to 2016 data from the Japan Congress on Evangelism, 81 percent of Protestant churches in Japan have fewer than 50 attendees. About a third have fewer than 15. Nearly three-fourths of pastors were more than 60 years old then, which means many still serving are now in their 70s.

Many pastors feel unable to retire because there are few trained younger pastors to fill their spots. A 2018 Tokyo Christian University survey found that 6 percent of churches don’t have a pastor. A similar number of congregations share a pastor with another church.

These dire statistics are what brought me to Japan to meet Akasaka at Japan Bible Seminary in Hamura, a semi-rural municipality about a two-hour subway ride from central Tokyo. I spent about two weeks in Tokyo and Sapporo, meeting Christian leaders and missionaries from various backgrounds, to get a sense of the future of Japan’s church.

Photography by Ben Weller for Christianity Today

Photography by Ben Weller for Christianity Today Photography by Ben Weller for Christianity Today

Photography by Ben Weller for Christianity TodayJapanese Christians are brutally frank about their situation. Akasaka speaks at more than 40 churches across the country. He sees a trend: white-haired pastors preaching in buildings occupied only by a handful of white-haired congregants. Akasaka, at age 64, is often the youngest among them. “It’s discouraging,” he said, sighing. “It’s discouraging for the older generation to not be able to see younger energy. They don’t know how to attract younger people, and they’re not even successful in passing their faith to their own children and grandchildren.”

Tales of demise abound. I heard of a Mennonite group in Hokkaido that planted 10 churches. Today, only two are still operating while the other eight sit empty, the children and grandchildren of worshipers long gone occasionally opening windows to air out the stale sanctuaries.

Or consider an American missionary who, in the 1960s, envisioned planting 100 churches across Japan. As the story goes, he planted about 40, of which only about a dozen have surviving buildings. Of those, two still hold services; some of the others house widowed pastor’s wives.

When Akasaka was a student in Michigan in the late ’80s, people would ask him, “When do you think a revival will happen in Japan?” He would reply, “When Japan’s economy hits the ceiling and plummets, maybe then people will turn away from Mammon and turn to God.”

In the ’90s, the economy tanked and never fully recovered. Last year, the Japanese yen sank to its lowest point in 34 years. “I’m still waiting for that revival,” Akasaka told me.

There have been almost, maybe, not-quite revivals. After World War II, hundreds of missionaries, mainly from the United States, arrived in Japan with food, clothing, and Bibles to fill the “spiritual vacuum,” as General Douglas MacArthur called it. “If you do not fill it with Christianity,” MacArthur warned, “it will be filled with communism.” He called for 1,000 American missionaries to go to Japan, and more than 1,500 responded within five years.

After losing the war, Japan was spiritually and physically defeated. People were scraping by on meager potato rations. They were shocked by the devastation of two atomic bombs and the revelation that Japan’s emperor wasn’t an all-powerful god. Most missionaries were earnest in their desire to heal Japanese souls and bodies. With the help of wealthy Western donors, they built churches, schools, and hospitals and won thousands of converts.

“But I’m hesitant to call it a revival,” Akasaka said. “The missionaries came with power and prosperity—and the gospel.” Churches were packed and an evangelism tent could draw hundreds. People were hungry for something—but was it the gospel or the power and wealth represented by the white benefactors whose country had chastened theirs? “When the missionaries left,” Akasaka said, “people lost interest in Christianity.”

But then, starting around the late ’70s, another church planting movement budded, this time mostly through the efforts of local Christians. Those were exhilarating, optimistic years, a period of rapid economic growth during which Japan surpassed the United Kingdom in purchasing power parity per capita. Many were called to ministry; most of the pastors I met, including Akasaka, attended seminary during that period.

In 2003, when Japan Bible Seminary hired Akasaka as one of its few full-time faculty, they were expecting the student body to grow. At the time, the school enrolled around 60 students.

By 2010, it was clear to Akasaka—and to the 30-something evangelical seminaries in Japan—that enrollment was declining instead. This year, Japan Bible Seminary had just five new enrollees. And that’s a relatively large number—many Japanese seminaries can count their students on one hand. Some years, there are none.

In Shūsaku Endō’s novel Silence, a Portuguese Jesuit priest commits apostasy after years of seemingly successful missionary efforts in Japan. When another priest confronts him, he declares,

This country is a swamp. In time you will come to see that for yourself. This country is a more terrible swamp than you can imagine. Whenever you plant a sapling in this swamp the roots begin to rot; the leaves grow yellow and wither. And we have planted the sapling of Christianity in this swamp.

Endō’s work is fiction, but I saw similar discouragement among many Japanese Christians. While churches in neighboring countries such as China, South Korea, and the Philippines are booming and multiplying, Japanese churches are withering and dying. Are there not enough planters? Or is there actually something wrong with the soil? And if so, why would anyone want to plant in Japan?

Lam Wai Chan certainly did not want to. Everything he heard about Japan scared him: One of the hardest fields in the world. Lovely for tourists, terrible for missionaries.

Lam was raised in a Chinese Buddhist home in Singapore. The first Christian in his family, he worked for five years as a correspondent for Japanese media, then entered seminary in 2009. For some reason, Japan kept popping up in his mind like a poltergeist, unsettling him. “I couldn’t get rid of it,” Lam told me. “I tried to forget it. I tried not to think about it, but it was always there.”

Photography by Ben Weller for Christianity Today

Photography by Ben Weller for Christianity TodayHe didn’t want to be rich. He didn’t want to be famous. “I just wanted a peaceful, easy life.” It is one thing to suffer for God’s mission. Who wants to suffer for a mission that’s bound to fail?

His first year in seminary, a local Church of God pastor asked Lam to consider succeeding him. Lam, then a staunch Methodist, politely declined, using the excuse that he felt called to Japan. The pastor’s eyes lit up. “Oh! We have Churches of God in Japan!” he said. “I’ll introduce you to one.”

Eventually, the pastor connected Lam with Kanemoto Satoru, pastor of Nerima Church of God in Tokyo. Reluctantly, Lam found himself on a 10-day visit to Japan. It didn’t win him over. Japanese churches were so tight-knit, so closed-off, so… Japanese. He felt awkward and alien, like ketchup on a bridal dress. He felt he could never belong.

Then during lunch, Kanemoto and an elderly deacon pushed a piece of paper toward him, asking if he would return as a missionary.

Lam was 37 at the time. Cowed under the gaze of two elders nearly twice his age, he signed the agreement.

He returned to Singapore in a panic. What had he done? He tried to back out, but alternative career paths closed before him. Unexpectedly, his wife Janet received a job offer from a bank in Japan. “Why are you still fighting this?” she asked her husband. “It’s so clear God wants you to go to Japan.”

So by April 2013, when they arrived in Tokyo with their dog, Lam had decided that if God wanted him to serve in Japan, he would bring his A-game.

“I didn’t think I was going to save the world,” Lam recalled. “But I did think I was better than them. That I’m a plus.” He had grown a youth ministry in Singapore and led plenty of Bible studies. He figured he could bring his expertise and revitalize the comatose youth and the wasting church. “I was thinking, maybe they’re short-handed. Maybe they don’t know how to do it, maybe they’ve been stuck in Japanese churches for so long they don’t know the latest trends in ministry.”

That first year, Lam sat in the backseat of a car on his way to a conference. Kanemoto was driving and talking to another pastor in the front seat, discussing all the problems of churches and seminaries in Japan. By then Lam had heard it countless times. There is just no solution to this, he thought. And it struck him: “If it were me, I would have thrown in the towel.” Yet here were these two men still agonizing over it, still serving.

They are the beautiful remnants, Lam realized. “We like to talk about Japan’s less than 1 percent Christians as something horrible. But that 1 percent is a story of God’s divine provision—that no matter how bad the oppression is, you still have that 1 percent.”

Photography by Ben Weller for Christianity Today

Photography by Ben Weller for Christianity TodayLam said he heard God tell him, They have faithfulness. What about you? There’s a lot to learn from the Japanese church. Be humble and learn, and you’ll see how it is me who sustains and preserves my church.

In 2019, Kanemoto abruptly retired at age 71. Fewer than 20 members remained in the church. They asked Lam, by then an assistant pastor, to take over as senior pastor. Lam accepted. But inside, he was trembling. “I felt like I was taking over a sinking ship.” He wept on his knees, begging God for guidance. “What do you want me to do? I can’t do a thing. I’m a Singaporean, for goodness’ sake.”

Lam felt God say, Offer the church back to me.

“Okay,” Lam remembers responding. “You preserve your church then. You save your church.” And then he let go.

As the new senior pastor, Lam intentionally avoided making big changes. The worship is the same as it’s been for decades, with traditional hymnals and a piano. His main initiative has been focusing on prayer at the church’s weekly after-service meeting. There, they pray for specific needs and people, for family members and friends and newcomers who don’t know the Lord.

So when their church slowly doubled in size, they knew whom to thank.

Photography by Ben Weller for Christianity Today

Photography by Ben Weller for Christianity Today Photography by Ben Weller for Christianity Today

Photography by Ben Weller for Christianity Today Photography by Ben Weller for Christianity Today

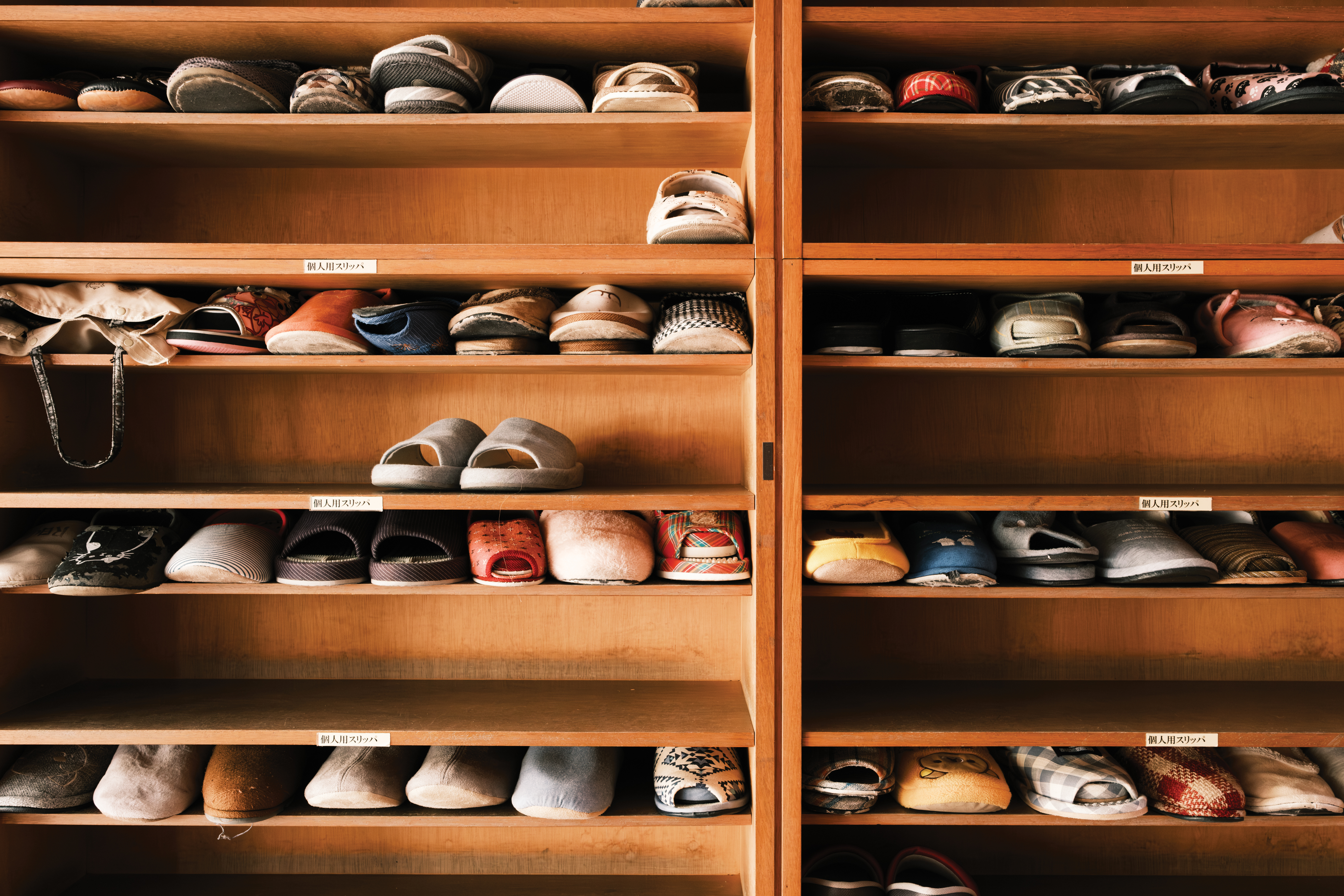

Photography by Ben Weller for Christianity TodayI visited Nerima Church of God the year it celebrated its 99th anniversary. It’s a cream-colored three-story building tucked between homes in suburban Tokyo. The 9 a.m. service, the first of two, is designed for children: Church members pushed the wooden pews with emerald-green velvet cushions to the side so that the children—about 10 of them, ages 2 to 8—could worship in the middle of the high-ceilinged sanctuary.

That Sunday, I watched the children dance, sway, and stomp to contemporary worship music. Lam squatted on a cajon, slapping away on the hand drum, while one deacon strummed a guitar and another shook a tambourine. For the sermon, copastor Ando Rieko used hand-drawn doodles to tell the parable of the sower while the children sat cross-legged before her. After they recited Matthew 13:23 from memory—perfectly—Lam raised his palms to pantomime an applause. He chuckled, looking delighted and proud.

Five years ago, Nerima Church of God had eight Sunday school teachers and one little girl. Now they have a full service for a dozen children.

At the 10:30 a.m. service, a family of three visited for the first time. They weren’t believers, but the teenage daughter attended a private Christian K-12 school where Rieko is headmaster and she wanted to check out the church. That’s typical of how the congregation has grown: Unchurched people just walk in, even though Lam does no special programs, marketing, or evangelistic events.

God told Lam he would preserve this church, the pastor said. “And he has never failed me once in these five years.”

Lam hears what outsiders say about the Japanese church; he used to say the same things. “I hear, ‘Oh, we need to give money, we need to support them, poor thing.’ No, it’s not ‘Poor thing’! Try surviving in such a harsh environment.”

He says the story of the Japanese church is the story of how God himself moves the church forward: “There’s a powerful testimony here.”

Photography by Ben Weller for Christianity Today

Photography by Ben Weller for Christianity TodayJapanese Christians may offer a powerful testimony, but at less than 1 percent of Japan’s population, they don’t have room to shrink much further.

Yoshinaga Kouki, a 44-year-old pastor in Sapporo, told me he worries about the future of Japan: “Even I, as a Japanese person, am not sure how to most effectively share the gospel in a culturally relevant way to bring more people to know Jesus.”

That stark reality has some church leaders wondering: What about turning to people who aren’t Japanese?

Japan’s population decline—driven by aging and an abysmal birth rate—is one of the world’s great demographic crises. But the number of foreign nationals has reached a record high of about 3 million, up 50 percent from a decade ago. And their churches—Filipino, Vietnamese, Nepalese, Chinese—are thriving.

Takashi Fukuda, the Asia-Pacific director at Wycliffe International, estimates that about 20 percent of those foreign nationals are Christian. If he’s right, that would amount to roughly 600,000 believers who are not accounted for in the Japanese government’s tally of 1.9 million Christians.

As a former missionary in the Philippines, Fukuda has built connections with multiple Filipino churches in Japan. Their members have Japanese spouses, neighbors, and colleagues. They have half-Japanese children and grandchildren who speak flawless Japanese and not a lick of Tagalog or English. And they’re eager to partner with Japanese churches.

Fukuda sees them as an untapped mission force. “There is a big need for collaboration between the Japanese church and ethnic churches,” Fukuda said. He is among those who have pushed for more visibility of Japan’s ethnic minority Christians within the leadership circles of Japanese evangelicalism.

At the 2023 Japan Congress on Evangelism, a gathering of around 1,000 denominational leaders, pastors, and missionaries to the country, attendees participated in the first ever “Global Night” to highlight Japan’s growing ethnic churches. It was the type of event that became standard fare at similar gatherings in Europe and North America decades ago. Fukuda called it a “major breakthrough.”

Others have joined this cause. When Iwagami Takahito first became general secretary of the Japan Evangelical Association (JEA), one of his priorities was to facilitate and strengthen the cooperation of evangelical churches across ethnicities and cultures.

“It’s the key for future missions in Japan,” he said. “We’re getting old. We don’t have enough evangelical power. But these ethnic groups are very active, very eager to witness Jesus Christ. If we work together, I think they will encourage us, empower us.”

The idea of turning to diaspora groups to revitalize the church is not new. In Europe, evangelical immigrants have become the main drivers of church growth. But Japanese Christians are only now warming to the idea.

One of the main speakers at the congress’s Global Night was Boie Alinsod, president of the Japan Council of Philippine Churches. Alinsod immigrated from Manila to Tokyo with his wife and 11-year-old twin daughters to start a ministry for Filipino immigrants. They partnered with a Japanese church, Shinjuku Shalom Church, which had been instrumental in helping Alinsod launch his own church in Manila two decades earlier.

Alinsod remembers feeling burdened for Japan after visiting in the early ’90s and being shocked by what he saw. At one Sunday worship service, only four people showed up: the church’s pastor, his wife, and their two children.

“It’s the exact opposite of what’s happening in the Philippines,” Alinsod recalled thinking. “In the Philippines, there’s an explosion of the gospel.” At the time, his own church was expanding quickly and preparing to plant another. But in Japan, the gospel seemed stuck. “I thought maybe, maybe, the Lord can use us Filipinos in some ways to help, to give something to the Japanese church.”

Alinsod returned to Manila and called his church to pray for Japan. Seven years later, in 1998, Shinjuku Shalom invited Alinsod to help build a ministry for Filipinos in Japan. The Filipino congregation fasted and prayed for 40 days, and then the Alinsods moved to Tokyo.

Twenty-six years later, the church Alinsod founded in Tokyo, Shalom Christian Fellowship, has multiplied to five church sites and 24 small groups, with more church plants on the way. “We’re reaching people,” Alinsod said. “People are getting saved, being discipled, and our disciples are turning into leaders serving the church.”

They are almost all Filipinos.

Alinsod’s vision to partner with Japanese churches to reach the Japanese has not quite materialized. Some Japanese pastors have felt they are already stretched too thin to manage a new partnership. Some have felt that what works for Filipinos won’t work for the Japanese.

But Alinsod has been praying for a breakthrough. In March 2014, the Japan Council of Philippine Churches began gathering pastors annually to pray for Japan. Since then, other organizations have joined in, including the JEA.

“There’s hope in the nation,” Alinsod said. “As long as there are people like us who will stand to represent Jesus in the nation, even our short prayers will really matter. Maybe not now; maybe we cannot see that. But God is faithful. We will one day know the effect of our contribution to this nation.”

As with Lam, a Singaporean who found himself inexplicably bound to a Japanese congregation, other pastors are stumbling into cross-cultural ministry.

Fukui Makoto is a 64-year-old pastor in Futako- Tamagawa, Tokyo, once a rural neighborhood that now gleams with department stores, trendy coffee shops, and the Rakuten global headquarters (about half its employees are from India). Fukui planted Tamagawa Christian Church and pastored it for 33 years. It was a typical Japanese congregation—until an American family showed up one Sunday morning in 2022. Then an Indian family came, followed by Korean Americans and Sri Lankans. None of them spoke more than a few basic Japanese phrases.

Fukui panicked. What was he to do? He began preaching in both Japanese and—by his estimation—“broken English.” With the help of a translation service, he prints sermon notes in English and provides copies for English speakers.

He still doesn’t fully understand why they decided to attend his church when there are other English-speaking international churches in Tokyo. And he still doesn’t know how to integrate all the worshipers into one church body. But his vision for the church has changed. For whatever reason, God saw fit to create some version of the multicultural scene from Revelation 7:9 at his church.

There’s no good alternative, said Masanori Kurasawa, a 72-year-old pastor in Chiba. “We need to take our eyes outside Japan. We need to see where God is moving now.” Masanori was the first Japanese pastor to tell me he feels “very optimistic” about the future of the church in Japan—mainly because of Japan’s growing diversity. When he retires, a young Korean pastor will succeed him. What will the Japanese church look like decades from now? He gave me a wistful smile. “I very much wish to see it, if the Lord allows me.”

In Silence, Endō likened Japan to a swamp. But Fukui prefers a different analogy. Japan is like cherry blossoms, he said. It’s not easy to accurately predict when they’ll bloom, and different trees bloom at different times.

As a new pastor more than 30 years ago, Fukui prayed for his church to grow. “Now, I understand people grow at different paces,” he said. “Some bloom early, some late. Pastoring a church is like raising children. You just have to continue to love. So God told me to love and wait.”

Photography by Ben Weller for Christianity Today

Photography by Ben Weller for Christianity TodayBack at Japan Bible Seminary, in Akasaka Izumi’s office, pastor Mizuno Akiko’s smiling face appeared on Zoom at 2:33 p.m. She was three minutes late. She had some technological problems, she said, apologizing profusely.

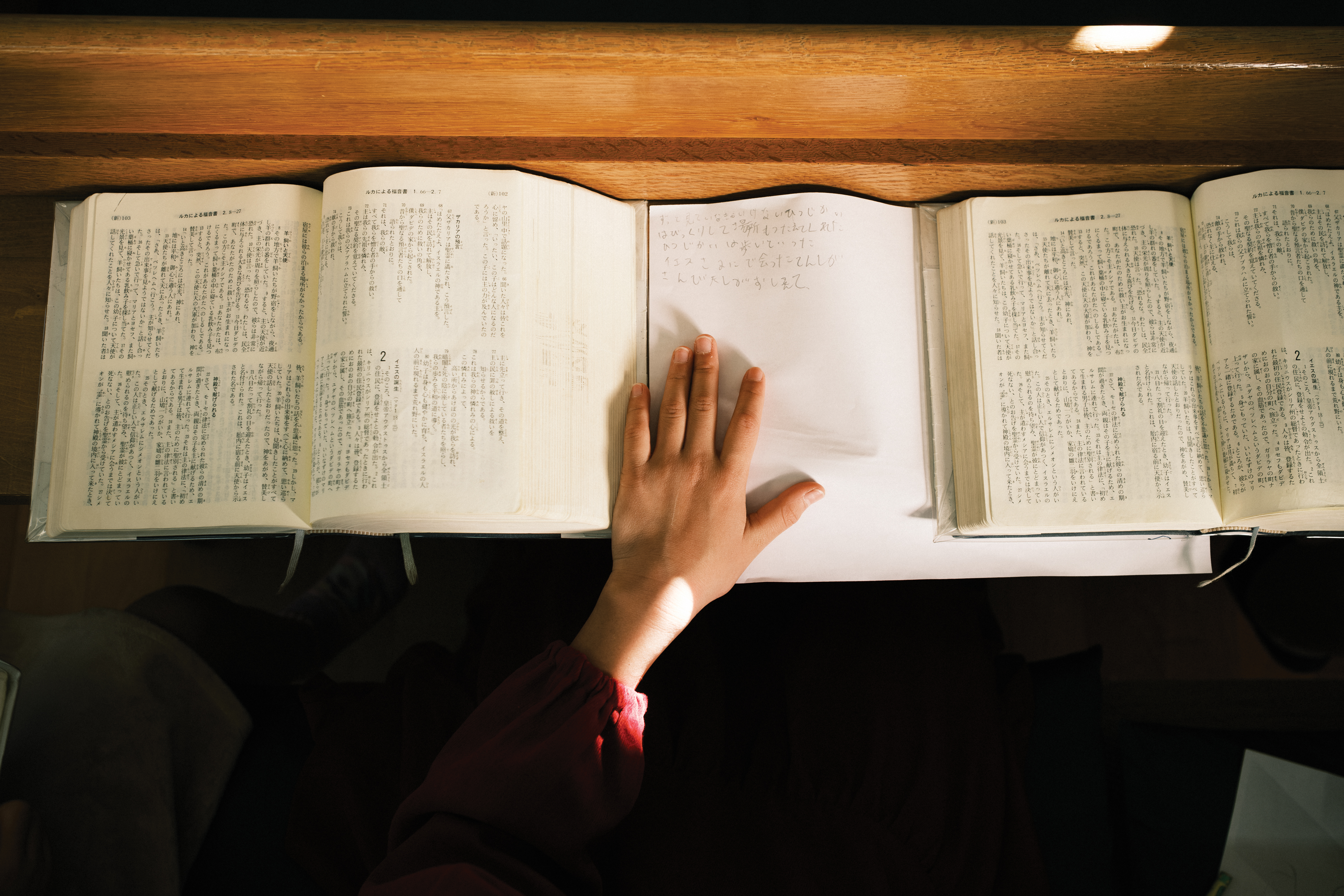

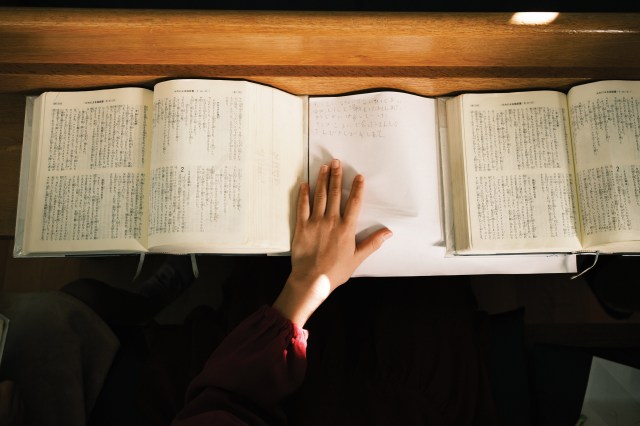

It had been another busy day for Mizuno. Every morning, the 73-year-old rises at 5:30 a.m. and reads her Bible. She records a daily devotional explaining one chapter of it. She does some light exercise then breakfasts on yogurt, bread, a banana, and coffee. And then the church doorbell starts ringing as people drop by for meetings, Bible studies, counseling, or help.

By the time she retires to bed around midnight, her eyelids are heavy.

Her life is not what she had envisioned nearly half a century ago as a 26-year-old fresh from seminary. Youthful and full of zeal, she took over as pastor of a new church plant in Ina, a city surrounded by rice paddies, pear trees, and cows in the mountainous Nagano prefecture.

Photography by Ben Weller for Christianity Today

Photography by Ben Weller for Christianity Today Photography by Ben Weller for Christianity Today

Photography by Ben Weller for Christianity Today Photography by Ben Weller for Christianity Today

Photography by Ben Weller for Christianity Today Photography by Ben Weller for Christianity Today

Photography by Ben Weller for Christianity TodayThe church started with about 10 members, mainly from two families. They met at a house. When Mizuno arrived, a deacon told her, “We won’t be able to provide a lot for you, but I promise you, you won’t starve.”

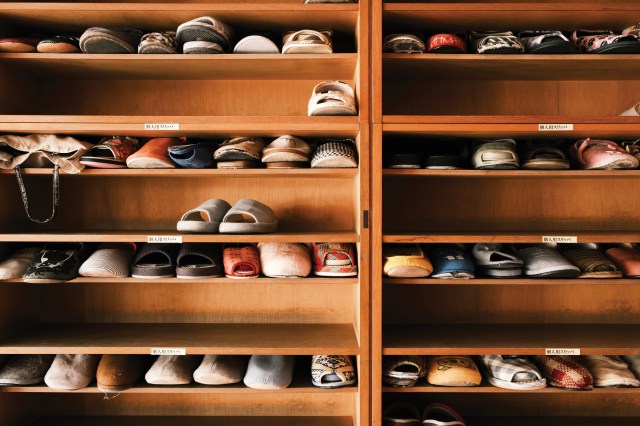

That was in 1977. At first, her work seemed to take off. On the opening day of her new children’s ministry, about 100 neighborhood children showed up. They threw their shoes off in a heap and squeezed into her tiny home where the church met, steaming the windows. The community—even non-Christians—was extremely welcoming, bringing her food and helping care for her elderly father when he fell severely ill. Everyone in the neighborhood knew about the church.

The congregation increased to about 40 members and became self-supporting in five years. It outgrew the little house and moved into a new church building (which also served as Mizuno’s home).

Mizuno got ambitious. It was the 1980s, when American televangelist Robert Schuller was pioneering church growth strategies that transformed the imaginations of evangelicals in the United States—and hers as well. Schuller’s model, epitomized by his polished, wide-reaching broadcasts and his shining Crystal Cathedral, dazzled Mizuno. She brainstormed evangelism tactics for her own church to draw crowds and win souls. “I was very energetic,” she said. “With my ideas and energy, I would drive the church to do programs.”

Event followed event, and 10 years later, “my church got physically tired and spiritually thirsty,” Mizuno said. “And I didn’t notice their thirst. I had lost sight of loving my members because I was focused on programs and church growth.” By the time Mizuno realized her error, the church had shrunk by half. Many had flocked to a seeker-friendly church that did not require much commitment. The remaining half was withering, spiritually dry.

Mizuno almost gave up. “I was so down emotionally, spiritually, and mentally that I didn’t have the confidence to continue serving or even to continue living as a human being,” she recalled. “I was so engrossed with doing something that I forgot to be a person who loves God and people.” She prayed: “Lord, help me be that person.”

Mizuno downsized and reset. Instead of focusing on growth, she focused on helping each person in the church meet God. She did start one new project: She encouraged everyone to read a chapter of the Bible with her every day. Most did. It changed their conversations, she said. People talked about what they read. Together, she and the church have read the entire Bible 10 times over two decades, and they’re still going. The congregation has grown to about 120 members.

Photography by Ben Weller for Christianity Today

Photography by Ben Weller for Christianity Today Photography by Ben Weller for Christianity Today

Photography by Ben Weller for Christianity Today Photography by Ben Weller for Christianity Today

Photography by Ben Weller for Christianity TodayAs a young pastor, Mizuno had prayed about marrying a fellow pastor and building a church together. Today she is still single and is unlikely to retire until she’s 80. But she’s content. She might not be rich, she said. But she never starved, just as promised, and she has stayed faithful to her calling. At the end of her life, she plans to tell God, “I’ve made some mistakes, but I was fully committed to loving you and loving your people. That’s what I wanted to do, and that’s what I was able to do.”

In Akasaka’s office, we bowed our goodbyes to Mizuno and left the Zoom meeting. I could tell that Akasaka was moved. He had known and respected Mizuno for years but had never heard about her struggles.

As the principal of a seminary with falling enrollment, it’s easy for Akasaka to feel disheartened. His board of directors decided against offering online classes—a common growth strategy—because they value in-person fellowship among the students and professors. They also voted against running a marketing campaign for the school, because they believe full-time ministry should be a calling.

Akasaka agreed with the board’s decisions, but he sometimes wonders if they were the right choices. “I don’t know. We are just trusting in God, waiting to see what he will do.”

Is Japan a swamp?

“Certainly the situation looks like that. There are no other words to describe it.”

Years ago, when he was still pastoring a church, Akasaka lamented the rise of wedding chapels in Japan. Christian-style weddings in churches, complete with choirs and altars, are extremely popular among the Japanese. It made him sad and frustrated that “fake” wedding chapels were grander and more popular than genuine churches.

One day, a woman in her 50s with an earnest, eager face told Akasaka, “This means God is preparing Japan for a revival. If a revival takes place now, we’ll need more pews, and I’m praying that God will one day fill the pews in those fake churches with real Christians!”

The woman’s childlike faith convicted Akasaka. “Her prayer became my prayer. I realized I cannot give up on Japan.”

Photography by Ben Weller for Christianity Today

Photography by Ben Weller for Christianity TodayBefore leaving Japan and flying back to my comfortable home in megachurch-packed Southern California, I grabbed tea with one of the students at Japan Bible Seminary.

Nakamura Mizuki is 30. He felt pulled to enter full-time ministry when he read John 21, where Jesus tells Peter, “Feed my sheep (v. 17).” It took him eight years to enter seminary because he was afraid. He was afraid he wasn’t worthy; he was afraid of poverty; but he was mostly afraid of failure. He had heard pastors sighing, year after year, “This year, still no baptism.”

He’s still afraid. Can he really do this? But he remembered Moses asked the same thing when God called him from the burning bush. God replied, “I will be with you” (Ex. 3:12).

“If this is God’s will, then I trust him,” Nakamura said. And so he is also excited. “I hope to share God’s heart with the church. I hope to share the gospel to many, many Japanese.”

That’s another reason Akasaka said he has not given up on Japan. “God has called people to serve Japan,” he said—people like Mizuki and Mizuno, like Alinsod and Lam. “God has not yet given up on Japan.”

Correction: An earlier version of this story gave the wrong name for the seminary Nakamura Mizuki addends. He attends Japan Bible Seminary. The earlier version also gave an unclear figure for Japan Bible Seminary’s enrollment in 2003. The school enrolled around 60 students at the time.

Sophia Lee is a writer based in Los Angeles.