Nelson and Gladys Gonzalez almost left the United States the easy way. It was 1996, half a decade after the Colombian couple came to the country illegally and found their place in the sunscape of Orange County, California.

Their home at the time, a unit in an apartment community in Laguna Niguel, evinced an American dream not fully realized but well underway. Outside their door waited the standard community pool and tennis court. Their daughter had started elementary at a good school. Nelson, a handyman entering his 30s, was earning, to his mind, good money.

None of which kept Nelson’s relatives in Colombia from goading them to move home.

“Why don’t we go back to our country?” Nelson would ask Gladys. “I want my kids to grow up with their cousins.”

Gladys resisted. She never intended to return, aside from the occasional visit they had yet to make because they were still trying to resolve their undocumented status. The subject of moving was a rare area of disagreement between her and Nelson. “We always had this little affliction in our marriage,” Gladys said.

Nelson worked on her. Some of his Colombian family owned taxis. They were doing well, he reminded Gladys. If they pinched and saved a little longer, they could afford to buy maybe two or even three taxis and live comfortably in Bogotá, Colombia’s capital.

In time, Gladys relented and agreed to go back. She started shopping to outfit a home there. She packed.

Their departure, however, required at least one painful task: The Gonzalezes had to tell their church. Over just a few short years, they had knit themselves into the fabric of Misión Cristiana Fuente de Vida, a scrappy Pentecostal congregation that met in rented office space in nearby San Juan Capistrano. Nelson and Gladys were baptized in the backyard of one of its members.

For weeks, they put off sharing their news. Then, during the service one Sunday morning, the pastor invited anyone who wanted prayer to approach the front. Nelson and Gladys went forward and found themselves standing before Lucia Moya, the pastor’s wife. They told her only that they needed prayer for a decision they had made, offering no further details.

Moya, a woman decades their senior with a reputation for prophetic gifts, stretched out a hand and prayed. Then she told them she had heard from the Lord: That decision is not God’s will, she said. Don’t go forward with it.

The Gonzalezes unpacked the next day.

It wasn’t difficult to believe God wanted them to remain in the country. Nelson and Gladys had arrived at a time when America’s embrace of unlawful immigrants was unusually warm. In 1986, a few years before they came, Congress passed a bill that granted residency to 2.7 million undocumented immigrants. President Ronald Reagan signed it cheerfully into law. In 1990, Congress empowered the president to grant temporary protected status to entire groups of immigrants who would be in danger if deported back to their countries.

Nelson wanted to submit to God’s will, but the about-face on their move left him angry. When he tried to revive the issue of returning to Colombia, Gladys would rejoin, “No, the Lord was very clear.” He didn’t fully let it go until their second daughter was born about a year later.

“I was thinking at that point more about myself,” Nelson told me in an interview this year. “But I realized we had two daughters, and the opportunities they have in California compared to in Colombia—I said, You know, I’m going to just stay here and work hard.”

And so they stayed, for 35 years, 2 months, and 27 days. Until the clock ran out on February 21.

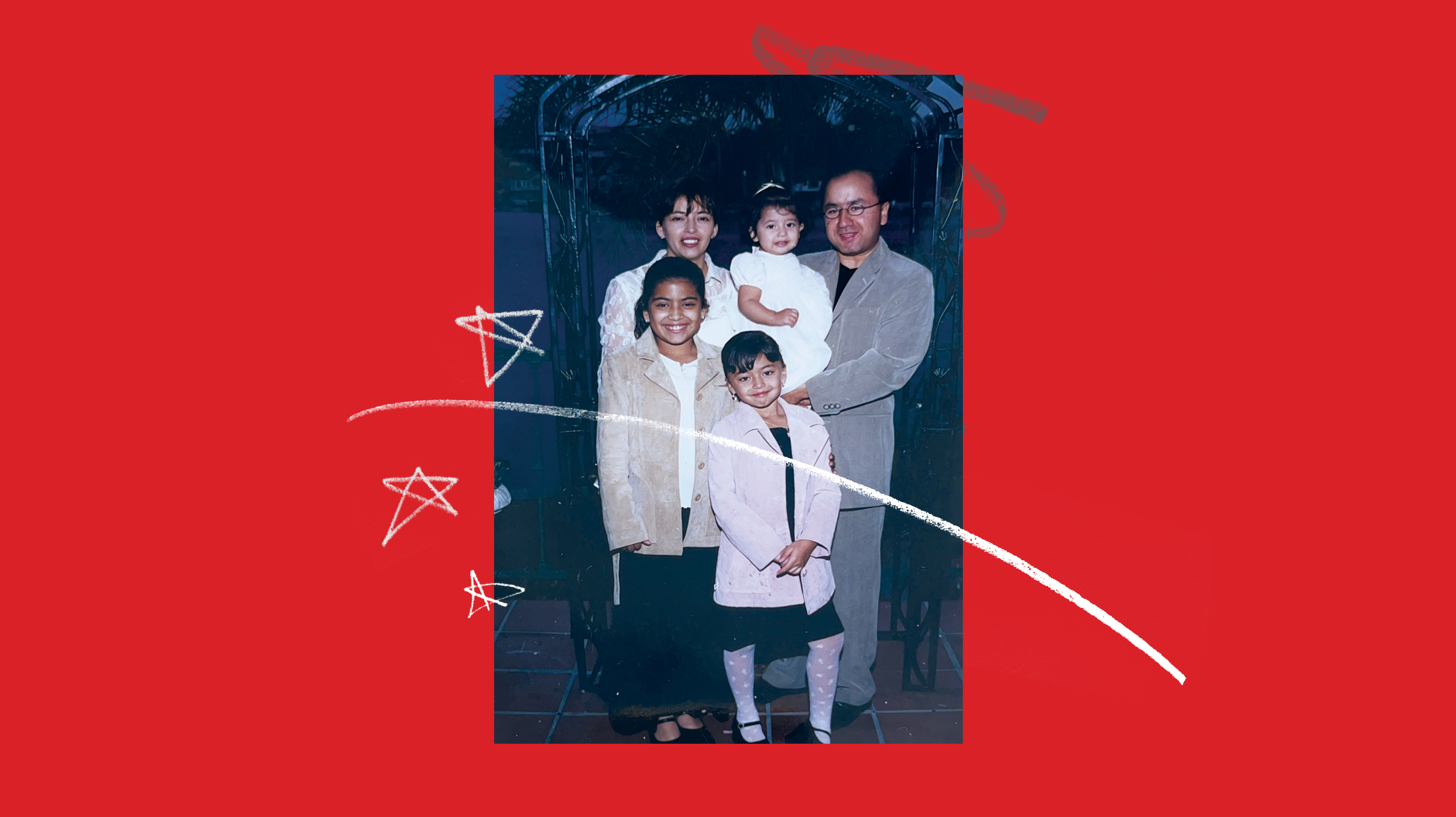

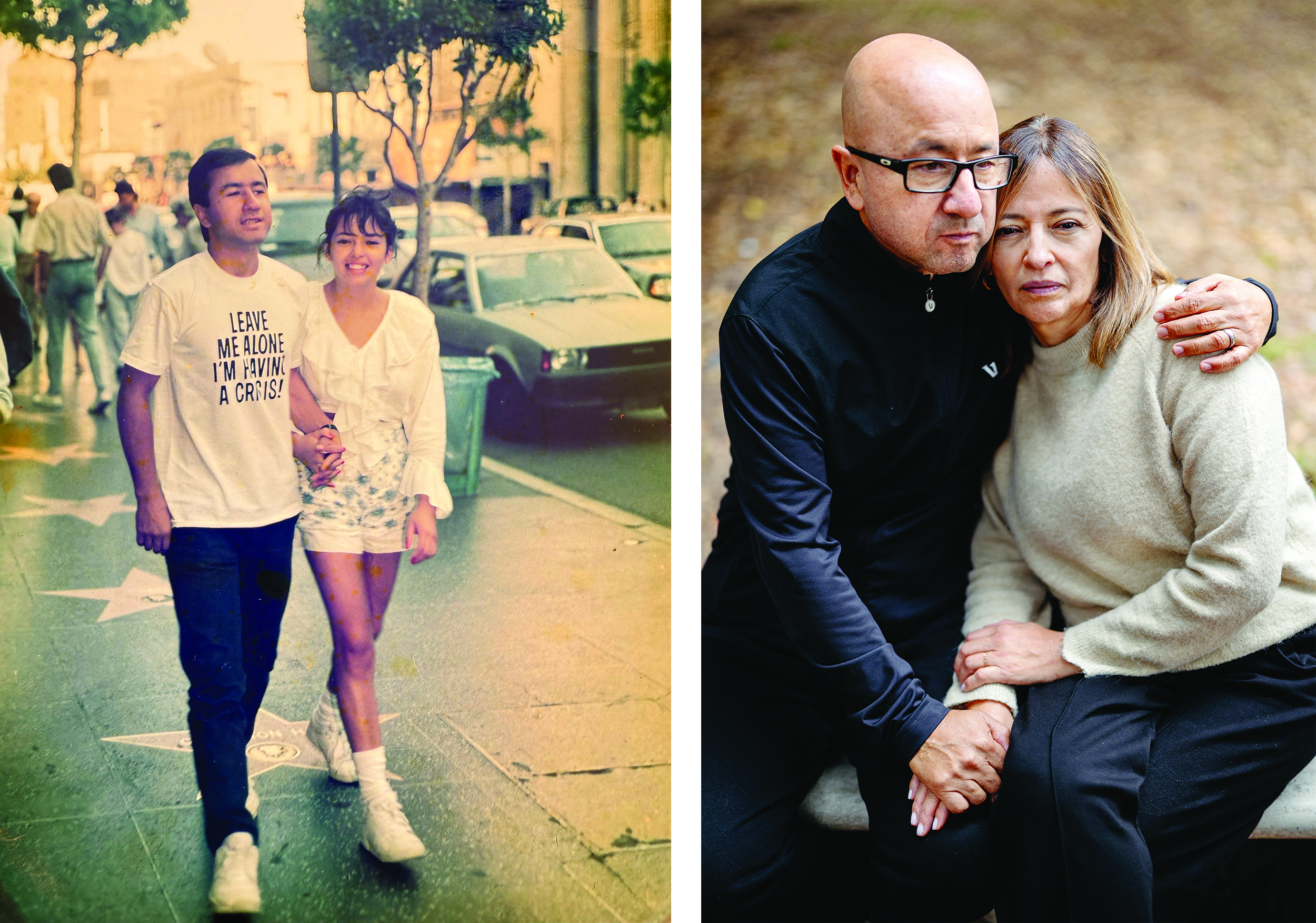

Left: Courtesy of Gonzalez family. Right: Photograph by Julian Barreto for Christianity Today.

Left: Courtesy of Gonzalez family. Right: Photograph by Julian Barreto for Christianity Today.I first learned about the Gonzalezes’ arrest in a message from a colleague in Orange County. She said her housecleaner was in a Bible study with Gladys. She could put us in touch if I wanted.

Of course I did.

Early news reports about the Gonzalezes recounted a story that was startling at the time but is now numbingly common in coverage of deportations under President Donald Trump’s second administration. A couple with no criminal record. A successful life upended. A family torn in two.

Journalists are drawn to such characters, probably to a fault. I understand why people tire of influencers who shout about the abuses of Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) without acknowledging that deportation is, still, a legitimate state tool for restraining the violent. But I also understand why people grieve the entire institution of deportation. I am among them. Tearing a life away from a place, even if lawful, is a trauma. Don’t rejoice when your enemy suffers, Solomon warned in Proverbs—it displeases God (24:17–18).

I traveled to California, and eventually to Colombia, to meet the Gonzalezes and walk for a minute in their world. Cards on the table: I was smitten.

Nelson and Gladys are eminently likeable. After they eventually switched to worshiping at Saddleback Church, for example, they came about as close as laypeople could to being the heart and soul of one of the megachurch’s campuses. Or consider that federal agents, whose job it was to deport Nelson and Gladys, on multiple occasions couldn’t bring themselves to do it.

Documenting their 2025 arrests raises certain questions. There is the great unresolved end goal of the president’s deportation program, now ballooning on a stunning scale. Most evangelicals, polling shows, do not think immigrants like the Gonzalezes—long-established, upstanding—should be removed from the country. How could knocking the pillars out from under a community be a desirable outcome of upholding the law?

But other questions are more pragmatic. When I mentioned the Gonzalezes’ story to friends or Uber drivers or seatmates on a flight, the immediate reaction was almost always perplexity. How could anyone exist in the United States for 35 years without getting their papers?

The answer, in part, is that within the fold of upright immigration lawyers also lurk predatory charlatans. Nelson and Gladys attracted them in spades.

The Gonzalezes shared their legal file with me. In it, hundreds of pages chronicle their search for a passage through the ramparts of America’s immigration system.

Among the documents are billing records from half a dozen lawyers that read like a ledger of gambling losses: a $1,400 wager on an attorney eventually disbarred for fraud; $7,000 on a lawyer who never filed their paperwork; thousands more on an attorney who coached Nelson and Gladys to lie to a judge.

As you might expect, the Gonzalezes confided their legal struggles only to their children and a few of their closest friends, filtered through the couple’s imperfect understanding of the situation. It’s not even clear that Nelson and Gladys realized, decades ago, when their immigration status drifted past the point of no return.

Many immigrants pass the bulk of their days in the shadows. More remarkable to me than the span of the Gonzalezes’ time in America is that they carried this weight in secret, enduring such uncertainty for so long. How did they sustain the faith to build a life they had been warned could be, at any moment, stripped away?

They met like a couple in a screenplay. It was 1988, and Gladys was 18. Her family had just moved to Villas de Granada, a community on Bogotá’s northeast side featuring green and yellow and red homes wound tightly around a soccer field.

Gladys studied in the mornings to be a bilingual secretary and worked in the afternoons at a shop selling underwear. She came home from the store early one day to find herself locked out.

Nelson emerged from next door and offered to help. Four years older than Gladys, Nelson played semiprofessional soccer. “I can jump anything,” he would boast. He climbed the wall of Gladys’s home, vaulting into her patio and sliding the back door off its hinges to let her in.

Within two years they were discussing marriage. But Bogotá in 1989 was a place that tested young dreamers. Drug cartels and paramilitary groups assassinated public figures nearly every month—at the airport, at street intersections, in public parks. Once while she was at work, Gladys heard a car bomb explode nearby.

Nelson and Gladys’s real trouble, however, was their lack of job prospects. Her English was not progressing as she wanted, and an expected job at a bank hadn’t materialized. He was taking university classes and working in the plastics department of an appliance manufacturer, feeling like his life was taking too long to launch.

“I wasn’t making enough money to support a family in the way that I needed,” Nelson said. Gladys’s older brother, who lived in the United States, told her over the phone, Why don’t you come here? Just come. Crossing was simple. A friend of Gladys’s father worked at the Mexican Embassy; he secured her a visa so she could fly as far north as Tijuana.

Nelson told Gladys he was coming with. He didn’t want to lose her. “It was mainly love,” he told me. “We were like kids. We didn’t think about what we were doing.”

He sold his television and his best soccer cleats to pay for airfare.

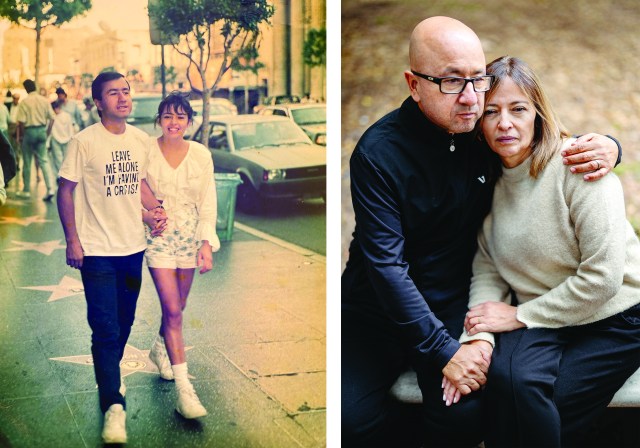

Photographs by David Fouts for Christianity Today.

Photographs by David Fouts for Christianity Today.The Gonzalezes talk often about how God has always been with them, even when they were breaking the law. After they landed in Tijuana, they sheltered for an afternoon at an abandoned house, where a friend of Gladys’s brother, a man who would serve as their guide, had told them to go.

At dusk, their guide took them to a nightclub near the San Ysidro border crossing, where lane upon lane of vehicles extrude through the port of entry, and instructed them to wait there.

They had never been in a club. For several hours, Nelson and Gladys watched in curious horror as young American men swilled beer through funnels, an introduction to the cold reality of the border: You could flow freely south to behave badly, but heaven help anyone pushing north.

The plan was drawn on a map. Around midnight, Nelson and Gladys would approach an opening somewhere along the border, which at the time included stretches of low, compromised chainlink fence. American border agents would change shifts. Then go—five minutes tops to slosh across the puddled Tijuana River and sprint through the gap before the next shift came to its senses.

It’s impossible to imagine such a convenient feat occurring at today’s US-Mexico border, with its towering wall, soldiers, buzzing drones, and motion detectors. But in late November 1989, as the hands of the clock scissored toward vertical, Nelson and Gladys slipped from the shadows and prepared to run.

They and everyone else. All around, other bodies materialized from behind trees and walls—hundreds of men, women, and children. The sheer quantity startled Gladys, as if here there was no strength in numbers, just the opposite. When the crowd broke for the crossing, Gladys froze in panic, couldn’t move her legs. Nelson and another man lifted her by the arms and carried her between them.

They entered the United States in a construction zone, rushing toward earthmovers at rest amid some excavation Nelson could not decipher.

The night around them erupted in chaos—someone screaming, babies crying, border patrol yelling from horseback and motorcycles. Their trio ducked behind a tractor, hiding in the lee of its rear wheel.

Gladys lost one of her contact lenses. In the dark, she groped in the sand and, by some miracle, came up with the lens on a fingertip. She licked it clean and put it back in her eye. Nelson felt sure they would be caught. “When you were a kid and you played hide-and-seek, if you saw a big tire you would say, ‘Bingo, there are people behind that tire,’” he said.

But nobody checked.

“We’ve always seen the hand of God,” Gladys said.

Less than an hour later, they were in their guide’s truck, speeding north on a freeway through San Diego.

Tucked into a 1970s housing development in Mission Viejo, Teofilo and Cecilia Pinto’s house was a landing pad for Colombians arriving in southern Orange County. The Pintos, old friends of Gladys’s family back in Bogotá, were devout cristianos, the Spanish catchall for evangelicals and other non-Catholics.

“If he knew they were Christian,” one of their sons told me about Teofilo, “100 percent, they would open the doors.”

Except that Nelson and Gladys weren’t Christians when they arrived at the home before sunup on what, as best they remember, was either a Friday or a Saturday. They wanted nothing to do with cristianos. It had annoyed Gladys in Colombia when church people came to the door and proselytized.

“Our families felt like, Oh, they want to brainwash you,” Nelson said. Now here they were, an unmarried couple, renting a room from a man and woman who didn’t hide their disapproval.

And in this house, the Pintos told them sometime Saturday or the next morning, everybody goes to church on Sundays. So the first place Nelson and Gladys ventured out to visit in America was International Christian Church, a local congregation now long gone.

I don’t know how I would have behaved in this environment less than 72 hours after arriving in a foreign country. Nelson and Gladys chose assimilation. They accepted an invitation to profess faith in Christ, though they felt no strong conviction. “It was more out of respect for the family,” Nelson said. In a sea of cultural firsts, you do what you must to stay afloat.

The couple grabbed whatever work they could. They cleaned apartments. Nelson began painting, blistering his hands using undersized rollers. At night he washed dishes at a Bennigan’s, soapy water stinging broken skin. “I know God’s got something better,” Nelson told himself as he pushed through the pain.

His work ethic caught a manager’s eye at a Laguna Niguel apartment complex where he was painting, and he was hired onto the maintenance team. He learned hard skills that would serve him for life, fixing microwaves and elevators and ceiling lights. The new gig also came with a discounted apartment.

For a year, Nelson and Gladys saved money toward a wedding. (You cannot just live like that, the Pintos and other church friends were telling them. That’s not God’s intent.) They knew nothing about engagement rings or wedding gown protocol; they drove together to pick out a dress and tuxedo.

In November 1990, a pastor friend married them at a rented church in nearby Aliso Viejo. Another Colombian friend cooked the food for their reception. There was no dancing; they toasted with sparkling cider.

A year later, almost to the day, their daughter Jessica was born. Around this time, the Gonzalezes were invited to another church by a neighbor named José Montoya, who once on his way to church had stopped a cocaine dealer and invited him to come along.

Misión Cristiana Fuente de Vida felt different from Nelson and Gladys’s earlier experiences with Christianity. The San Juan Capistrano congregation was tambourine-boisterous and full of people balancing on the edge of calamity, like a 6-year-old who brought a knife to church and said he needed it for self-defense.

Jorge and Lucia Moya, a Costa Rican couple who pastored the church, handed out clothes in parks and threatened to report employers who withheld wages from undocumented parishioners. “When they come to this church, they are under our protection,” Jorge Moya told a reporter a few months after the Gonzalezes began attending.

On their second Sunday worshiping there, Nelson and Gladys found themselves walking forward to accept Jesus as their Savior for the second time in a year. Nelson began weeping. A highlights reel of sins played on the screen of his mind. “It was like a movie,” he said. “Fifteen seconds. God showed me things I did not even remember—I saved you from this, from this, from this.”

In 1992, Nelson was fired. New management at the apartment community flagged him for not having work authorization. He asked around for a lawyer to get their immigration status sorted. A Los Angeles man named Mario Mejia came recommended.

When the Gonzalezes met with Mejia, he advised them to request asylum; he had secured asylum for another family and could probably do it for them.

How much does the average American know about the knotty statutes that govern US immigration? How much could anyone reasonably know who spoke little English and inhabited a pre-internet universe?

To qualify for asylum in the United States, applicants must demonstrate, among other things, that they face harm in their home country because of their association with a social group—often their politics, their profession, or their faith. The Gonzalezes are quick to say that this was never them.

But Mejia spun a tale on their asylum application so convoluted that I could hardly believe anyone would hand over such a document to the federal government. He outlined, in clunky, error-riddled sentences, how the couple had been members of the National Liberation Army, or the ELN, a leftist paramilitary group.

Imagine seeking the government’s mercy by appealing to your clients’ involvement with a violent group the State Department today designates a terrorist organization. “The lawyer just made something up,” Nelson said. He and Gladys received an appointment for an asylum interview, a standard next step where an asylum officer would assail them with questions designed to weed out opportunists.

Then, Mejia threw them a curveball: He told them not to do the interview. They didn’t have enough evidence, he said. So the Gonzalezes skipped their appointment.

Mejia failed to warn them that unauthorized immigrants who blow off an asylum interview are generally fast-tracked into America’s deportation mill. The legal costs of extraction from it—conveniently for Mejia—can pile up to tens of thousands of dollars.

At what point should Nelson and Gladys have known they were being hustled?

Eventually they would learn that Mejia was not, in fact, an attorney. He belonged to an industry of grifters, sometimes called notarios and still endemic today, who have little or no training in immigration law but present themselves as lawyers or accredited experts. Those fortunate to have never dealt with America’s immigration system may know nothing of this underworld, but the Gonzalezes and countless others have suffered acutely from it.

The irony: Nelson and Gladys fell prey to immigration fraud while trying to avoid immigration fraud.

A friend of theirs in California, who asked not to be identified, told me he secured his citizenship by paying an American woman $15,000 to sign a marriage license. He tried to convince Nelson to follow suit—divorce Gladys but quietly stay together. Buy a fake wife.

Nelson declined. It felt wrong, like Abraham disavowing Sarah to save his skin from Abimelech. “That is fraud,” Gladys said. (Immigration authorities are much more effective at sniffing out transactional marriages today, aided by social media and online paper trails.)

In the late ’80s, pressure to cheat was everywhere. Even within churches, Nelson said, he knew people who had purchased forged documents to qualify for Reagan’s 1986 amnesty program. A provision at the time that granted residency to farm workers enabled widespread fraud and has become a case study among pundits.

In working with lawyers to pursue legal routes to residency, Nelson and Gladys “thought they were doing what they were supposed to be doing,” Marianne Phillips, one of Gladys’s closest friends, told me. “I think they, if anything, might be a bit naive, trusting certain people.”

In July of 1993, the Gonzalezes opened a piece of certified mail containing an “order to show cause”—a notice to appear before a judge and explain why they should not be deported. They read it in horror.

Court records show this is the point at which they realized Mejia was not actually a lawyer. Mejia introduced them to Terrence McGuire, an attorney he worked with, and assured them not to worry, they were in good hands.

McGuire did get the court appearance canceled. And he put more time on the board—by filing a stream of deceptive documents that Monica Crooms Mkhikian, an attorney who represented the Gonzalezes years later, called “misrepresentation and an abuse of the asylum process.”

Among the highlights: McGuire filed two new asylum petitions in which Nelson and Gladys’s backstory differed in every way from the tale Mejia had concocted. In one account, they campaigned in rural towns for a presidential candidate who was assassinated in 1989. In another, Nelson worked in a photo lab for a criminal syndicate where employees who tried to quit wound up dead.

Three conflicting fictions, sitting side by side in a government file in Los Angeles, just waiting to raise eyebrows.

The Gonzalezes suspect McGuire knew he was digging them into a hole. When they were scheduled for another asylum interview in 1998, McGuire maneuvered again and again to push it back.

Eventually, they blew that one off too.

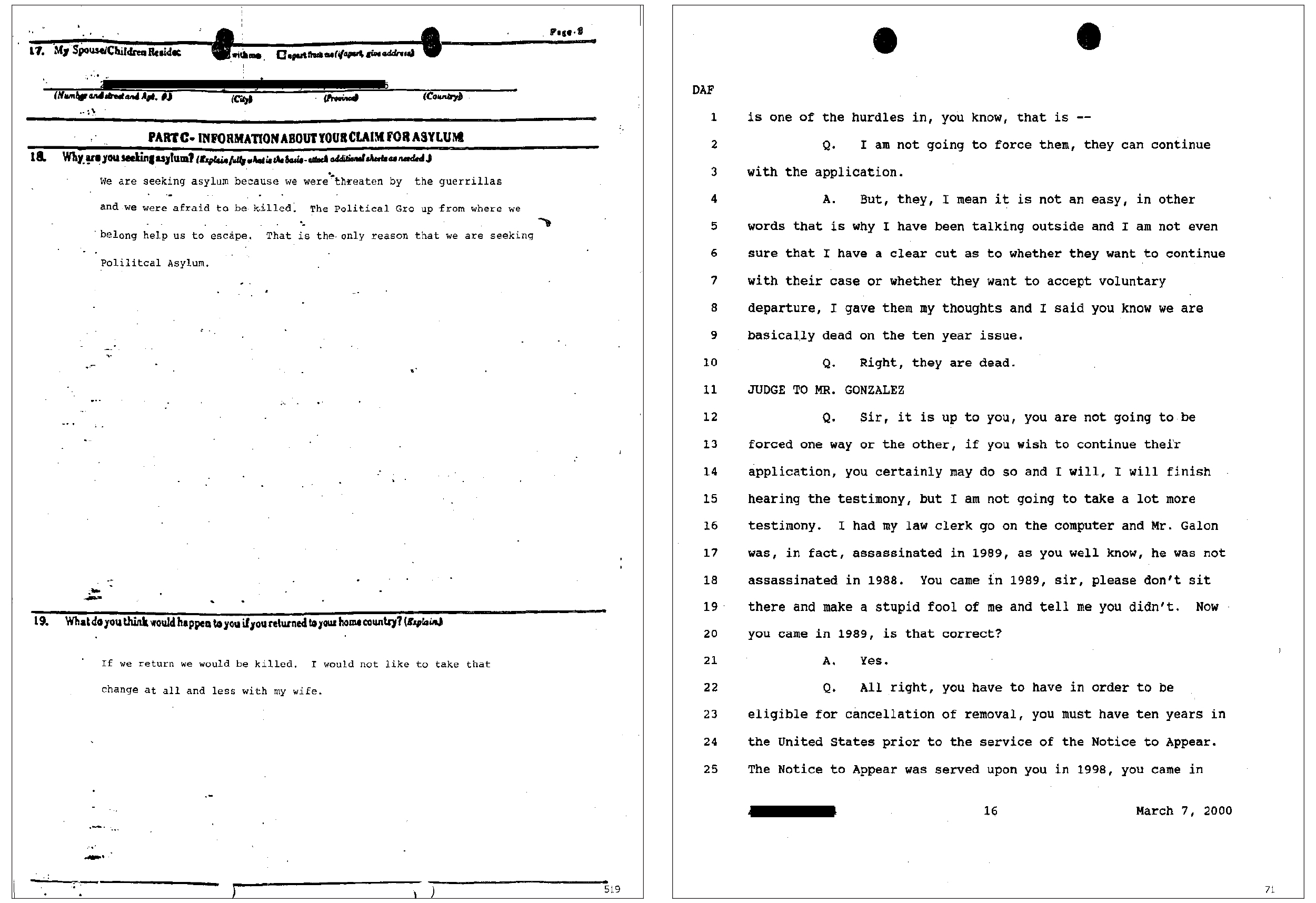

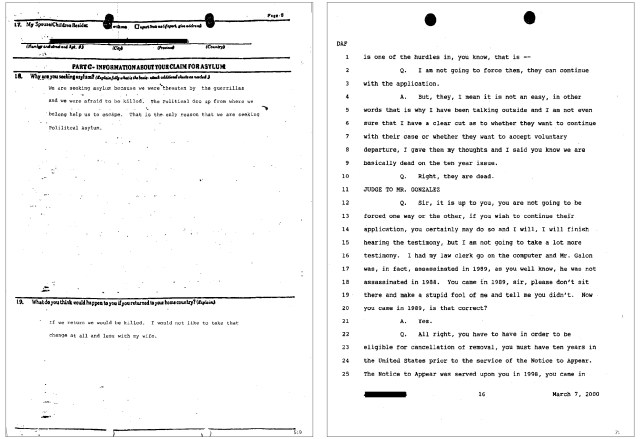

Documents courtesy of the Gonzalez family

Documents courtesy of the Gonzalez familyWhile their lawyer played games, the Gonzalezes got on with their lives. Nelson found work at a new apartment community, something he ended up doing several more times over the years.

He and Gladys took on a newspaper route, waking at two in the morning and lofting copies of The Orange County Register from the back seat of their car to second- and third-floor condominiums.

They also turned seriously toward their church, Misión Cristiana. Gladys taught Sunday school and became secretary of the women’s ministry. In 1994, Nelson’s parents visited from Colombia and gave their lives to Christ.

Then in 1998, a year after the birth of their second daughter, Stephanie, the Gonzalezes found another terrifying letter in their mailbox: an order to appear in immigration court for a deportation hearing.

When Nelson and Gladys contacted Mejia, he again assured them they would be fine. Then he dropped off the planet.

Mejia, it turned out, was under investigation for fraud. McGuire’s office, too, went suddenly dark. Soon after, McGuire was disbarred for ignoring court orders, falsifying immigration claims, and billing clients for work he never performed.

To prepare for their day in immigration court, the Gonzalezes turned to Robert E. Keen, another Los Angeles lawyer.

Keen told them, correctly, that new regulations required them to have lived in the country for 10 years to qualify for postponing their deportation. As of 1998, they had only logged nine years.

Keen’s solution: Lie to the judge about when they crossed the border. Say they came a year earlier—not in 1989 but in 1988.

It was an absurd strategy; the court already possessed sworn statements that the Gonzalezes had entered the country in 1989. Yet they heeded Keen’s counsel. At their court hearing, they lied.

In my conversations with Nelson and Gladys, I asked how they could have signed their names to so many legal documents shot through with falsehoods. The Gonzalezes insist—and they told the judge—that they never understood what the papers contained. At the time they had little grasp on English or the immigration system. Sometimes they never even looked at the documents. “We made so many mistakes,” Nelson said.

I struggled to believe this explanation—until during one interview, when I asked them about their decision to commit perjury in front of the judge. They immediately owned it. They were young and scared, Nelson told me. “That was the only time that I lied,” he said.

I found this convincing. What did the Gonzalezes have to gain by denying knowledge of their lawyers’ deceits but confessing to lying under oath? “That lie cost us everything,” Gladys said.

To read the court transcript of their final hearing is to feel Judge Dorothy Bradley’s glare 25 years later.

Bradley, after reading the various asylum petitions and challenging Nelson on the stories they contained: “You came in 1989, sir; please don’t sit there and make a stupid fool of me and tell me you didn’t. Now you came in 1989, is that correct?”

Nelson, filling with regret over the lie, which would haunt him for the rest of his life: “Yes.”

Keen, stumbling over his words and trying to compose himself: “You know we are basically dead on the 10-year issue.”

Bradley: “Right, they are dead.”

In her ruling, she ordered Nelson and Gladys to “voluntarily” depart the United States. She gave them four months to leave.

The Gonzalezes did not leave. Aided by several more attorneys (Keen, too, was eventually disbarred), they probed every corner of the US immigration system for ways to buy time. Their legal bills snowballed beyond $20,000. They fought all the way up to the US Court of Appeals for the Ninth Circuit, claiming ineffective assistance of counsel.

In 2020, the court ultimately declined to overturn their removal orders. (Appeals based on poor legal representation are difficult to win; unlike in criminal courts, there exists no constitutional right to representation in immigration cases.)

Lawyering alone, however, cannot account for how Nelson and Gladys were able to remain in the country for another 25 years after their failed court appearance. The primary agent of mercy for the Gonzalezes—and for so many immigrants to America—was ICE itself.

One morning, about a decade after the reckoning with Bradley, Gladys was herding their three daughters toward the car to get them to school. Two ICE vehicles with tinted windows pulled up, and a trio of uniformed agents approached. They opened a folder containing a photograph of Nelson.

Is this your husband? one agent asked. Could she call him? He needed to come with them.

Nelson was at work, Gladys explained. She couldn’t call him at that moment. Her kids would be late for school. The agents said they would wait.

When Gladys returned from dropping Jessica off at high school and Stephanie at middle school, she invited the agents into her home.

The men told her they ran her name and found a deportation order for her as well. They would also have to arrest her. Who would pick up her girls, Gladys asked, or watch Gabby, her crying 5-year-old who still needed to get to school?

Gladys remembers the agents were kind. One of them told Gabby, Calm down, nothing’s going to happen to your mom. One of them complimented the inside of her home. Gladys thanked them. “My husband painted this house.”

And the agents just left.

It feels obvious to pause here to set this in relief against the videos of ICE agents that now fill our newsfeeds—masked men smashing car windows and plainclothes officers snatching women off the sidewalk. In contrast, agents told the Gonzalezes they could check in the following day at an ICE office in San Bernardino once their girls were at school. Nelson and Gladys turned over their Colombian passports and were given 90 days to board a plane out of the country.

Arrangements like these, called orders of supervision, have been used for decades as an alternative to detention. They allow unauthorized migrants who pose no apparent public safety risk to remain free while pursuing legal appeals or preparing to leave, checking in regularly with ICE. Supervision also frees ICE to pursue higher-priority targets, such as migrants with violent criminal histories.

And it is cheap: The government spends more than $160 a day to detain a migrant, according to ICE. Migrants under supervision cost virtually nothing, are often granted work permits, and are usually paying taxes. (Records show the Gonzalezes faithfully mailed the IRS tax checks every year.)

After the first visit, agents dropped by their house every few weeks to monitor their progress toward departure. The frequency lessened over time. Eventually, Nelson and Gladys were switched to a rhythm of occasional check-ins at various ICE offices.

At one appointment, an agent sent the couple to a room to be fitted with ankle tracking bracelets, a common feature of supervision.

Nelson protested; he visited people’s homes for his job and could never show up at a door wearing an ankle monitor. He said he would rather be deported.

His supervising agent told him, I don’t know why, but I’m going to make an exception for you.

Further check-ins yielded further mercies. Once, Nelson met with their supervising officer and asked if they could have an extension in the country.

Absolutely not. Three months is three months.

He pleaded, “I have three daughters. When I came to this country, I had no experience. I made mistakes. But I don’t want my kids to pay for those mistakes. Please help me.”

The officer told him to bring in his girls’ report cards the following week, and she would see what she could do. Nelson obliged. All three had sterling grades. Stephanie was on the middle school honor roll.

Come back in six months, the officer said. She could work with them if they kept providing evidence that they were trying to do right. Just bring me something. Something.

Over the years, their check-ins became annual visits. They showed up to each one, praying for favor. Once, an ICE officer told them, Don’t worry. They’re never going to kick you out. You’re good people.

And on like that it went, for more than two decades.

If we fully grasped that time is a gift given to us—if every month of life were a precious thing we solicited at a bureaucrat’s desk—how would we choose to spend it?

Sometime after Lucia Moya, the pastor’s wife at Misión Cristiana, prophesied to the Gonzalezes and they canceled their return to Colombia, Nelson reached a conclusion: “God didn’t bring us here just to work. That wasn’t his purpose. We came to this country to know him and to pass that through the generations.”

The couple reconfigured their lives around that conviction. They relocated for several years to more economical surroundings in Riverside County. They decided early on that Gladys would stay home to raise their children, gleaning extra income when she could—for a season she ran a daycare from their home—but otherwise prioritizing motherhood. How they made ends meet, “God knows,” Nelson said. “He provided us with everything we needed.”

Nelson left apartment maintenance and got certified as a mobile phlebotomist, driving to eye-popping homes in Los Angeles and Beverly Hills and Pebble Beach, administering blood tests and electrocardiograms for customers purchasing high-ticket life insurance policies.

In the early 2000s, the Gonzalezes began attending Saddleback Church, the booming Orange County mega congregation led by Rick Warren. It was a risk, trading a tight-knit Latino family of faith for an incomprehensibly large, mostly English-speaking commuter church. But what Saddleback dangled before their growing daughters was too much to resist: Its main campus had entire buildings dedicated to children and youth.

The girls seized opportunities Nelson and Gladys never could. They took mission trips to Africa and Latin America. Stephanie eventually earned a master’s degree in theology and took a job as a high school youth minister at Saddleback.

While all this unfolded, Nelson and Gladys also took hold of what was in front of them: Saddleback’s Hispanic ministry.

The couple was leading some of the church’s earliest Spanish-language small groups when pastor Will Guzman came in 2017 to open Saddleback’s first Spanish-speaking campus, in Lake Forest.

Guzman recruited Nelson and Gladys to the launch team. He saw something “definitely rare” in the couple’s leadership potential. Soon, they were overseeing the campus’s discipleship and formation efforts.

“They’re hard workers, well educated, they love the Lord, they serve people,” Guzman said. “In the Hispanic world in Orange County, that’s hard to find, because people have two, three jobs. They just don’t have the time for church. The fact that they put a priority on serving the Lord is huge.”

The Gonzalezes and the Guzmans also became close friends. When Will and his wife needed someone to talk to about how to work less and spend more time at home with their children, they called Nelson and Gladys. When they needed someone to liven up a barbecue—Nelson is a fount of dad jokes—they called Nelson and Gladys. “They didn’t suck your energy out,” Will said. “They gave you energy.”

Anything, for Nelson and Gladys, could become a tool for ministry. Like their dog, a Jack Russell mix named Lola—they took her for walks and met neighbors, including the mother Nelson prayed with after her daughter was sexually assaulted. Or like Nelson’s long drives to collect blood—once he invited his visiting nephew to ride along for a few days and led the young man to faith.

As the world reawakened from COVID-19, Saddleback moved the Spanish-language congregation to its campus in San Juan Capistrano, a mountainside piece of land with a retreat center and a palm-rimmed lake. Spanish-language worshipers met in a large tent. An English-speaking congregation met separately in a chapel on the property.

That’s when Marianne Phillips met Gladys. Phillips led women’s ministry for the English speakers. She was struck by an impulse to see the campus’s English-speaking and Spanish-speaking women transcend their respective buildings and worship together. The 400-seat tent of the “Español campus” was nice, but it “wasn’t equal,” Phillips said. “I felt it was discriminatory.”

Phillips introduced herself to some of the Hispanic ladies and pitched an idea: What if the women’s ministries from the two congregations merged? “I didn’t talk with anyone about it,” Phillips told me, laughing. “I didn’t even consult with the pastors.”

The notion so touched Gladys that she burst into tears. She was the Hispanic congregation’s lay leader for women’s ministry, and she immediately championed the venture among the church’s Latinas.

Within a few years, the ladies of Rancho Capistrano (as the campus was called) became one of the most culturally blended communities at any of Saddleback’s campuses. They live-interpreted group lessons and devotions. They translated books and Bible studies so both English- and Spanish-speakers could learn the same materials at the same time. Their worship music swung, often awkwardly, from one language to another.

It was messy. Change unsettles. Women on both sides grumbled sometimes, Why do we have to do all this for them? But the success of the women’s ministry helped prime the pump for Saddleback’s decision, beginning this year, to fully integrate its Spanish-language churches with its English-speaking congregations.

“It was a data point to say, look, the discipleship can happen. It doesn’t have to be separated,” Guzman said.

A special memory for Phillips: At one of several joint women’s events she and Gladys planned, she remembers singing in the grassy courtyard of Rancho Capistrano’s retreat center. That night, just for fun, they organized a line dancing lesson beneath a canopy of string lights, Phillips marveling at how Gladys and the dozens of Latina church ladies could move their feet. “We called ourselves sisters,” Phillips said. “We really were doing God’s work together as sisters.”

Lives are charted in milestones. Jessica gets married and, less than a year later, Gladys stands at the bedside as her first grandson is born. Stephanie gets engaged to a Saddleback youth pastor named Joshua Quintino. Nelson and Gladys’s youngest, Gabby, is suddenly an adult and takes a job teaching preschool.

But it is astounding the details to which we might pay more attention if only we knew what was coming six months down the road:

The blond wood table where Joshua Quintino sits in late August 2024, the table he cannot know he is about to inherit, offering Nelson and Gladys almond croissants and asking their blessing to marry Stephanie.

The sermon that mentions the apostle Paul’s writings from prison, prompting Gladys to pray, “Lord, how would I ever be capable of being in a situation like that?”

Gladys’s dream, the one where she and Nelson are in a large, crowded room and the walls are closing in and they are pulling one another, running, trying to get to a door.

Nelson’s dream, where he is sitting atop a bunk bed, looking out over identical bunks arrayed in a large room.

The road sign Nelson and Gladys pass exiting Rancho Capistrano, on the last Sunday they will set foot there, that reads “Have a great week!”

The choice Stephanie makes to say goodbye to her parents on her way out the door to work on February 21.

Photograph by David Fouts for Christianity Today.

Photograph by David Fouts for Christianity Today.February 21 was a Friday. The worst day of their lives. Nelson and Gladys drove to their annual ICE check-in, this time at an imposing cluster of government buildings in downtown Santa Ana. The couple checked in at a self-service kiosk that spat out two pieces of paper: Nelson’s said he needed to wait to see an officer. Gladys’s said she’d received a one-year extension.

She talked to Stephanie on the phone: Good news. Another year. They waited in a lobby for nearly three hours then were called into a room where an ICE officer skimmed Nelson’s file and announced they were being detained.

Mortified, Gladys asked why. “I was approved for another year.” The officer: Oh, we made a mistake.

They had always been given more time. Could they at least go and speak with their daughters? We have an order from the new administration. We can’t let people go anymore.

The Department of Homeland Security, under Trump, has made clear its disdain for orders of supervision and other forms of non-detained enforcement. It scaled back their use during the first Trump presidency. And this July, ICE directed immigration judges to stop granting bonds to most detainees, eliminating the primary means by which immigrants are freed from detention, including millions without criminal records who previously would have been considered for release.

This year, arrests at routine supervision check-ins have surged. Nelson and Gladys were some of an estimated 1,400 people seized at their check-ins during the first month of the new administration, around double the number during a month of the Biden administration.

The growing abolition of discretion, perhaps more than any other aspect of the administration’s immigration suppression, will cause the deepest pain for many families that previously had little to fear.

Individuals within the US immigration edifice have long had some authority to exercise compassion in situations where, in their judgment, the cost to society of a person’s removal might be higher than the cost of nonremoval. One could view such discretion, as the Trump administration does, as a weakness. Or one could see discretion as the cardinal quality that separates a human justice system from a cold enforcement machine with all the sensibility of a red-light camera.

In a statement, ICE said the Gonzalezes “exhausted all legal options to remain in the US.”

They were ordered to hand over their phones and remain silent. They were handcuffed and moved to separate rooms.

On an office line, Nelson made one last phone call, to Jessica, who frantically conferenced Stephanie into the call.

Come pick up the Tesla, Nelson told his daughters. (“They bought their dream car last year,” Stephanie said.) He told them to remember to park it in one of the apartment spots where it wouldn’t get towed.

“My dad, just being a good dad,” Stephanie told me.

For the sisters, a weekend from hell: Jessica and her husband drove to Santa Ana in a fruitless attempt to locate her parents. Stephanie called lawyers. She called ICE phone numbers Friday night and into the early hours of Saturday until she pinpointed Nelson and Gladys at two separate California detention centers. “I felt like Liam Neeson,” she said.

The sisters drove two hours to see their dad at the detention facility in Adelanto, California. Visiting their mom proved more difficult. From Adelanto they drove three hours south to where she was being held, in Otay Mesa on the Tijuana border, only to be turned away at the entrance. They weren’t cleared to visit her until two weeks later.

Early on in their parents’ confinement, the sisters huddled at Jessica’s house in Newport Beach—it was too depressing to be at their parents’ apartment—and told almost no one what was happening. What if Nelson and Gladys were about to be released? If so, they didn’t need to broadcast their immigration status. “This was super sensitive,” Stephanie said. “A lot of people didn’t know.”

Women from Saddleback began messaging her. Hey, where’s your mom? Is she coming tonight? She’s not answering her phone.

As reality sank in, the sisters decided to open up. At Saddleback, a 24-hour prayer group materialized. Church members organized prayer nights. Stephanie launched a GoFundMe that soon raised more than $82,000 to cover legal and family expenses.

Even with the support, navigating the vagaries of ICE felt like stumbling across a landscape where nothing is where it’s supposed to be. On a phone call with one officer, Stephanie was told that her parents’ passports were missing and they could not be released to Colombia without them.

“Okay, but what can we do?” Stephanie asked. “Because you guys took them. You guys lost them.”

Soon after, Stephanie and Gabby walked into the ICE office in Santa Ana to try, unsuccessfully, to track down the passports. They explained the situation to an agent, who listened and then said he could not help.

Then the agent added, I was the one who made the arrest.

Stephanie went cold. She didn’t know what to say. On their way out, she and Gabby ducked into the women’s restroom and cried.

A flash of light, a small piece of normalcy: The sisters established a nightly schedule for video calls with their parents. Nelson would ring at 8 p.m., Gladys at 9. The sisters kept their phones ever close and checked obsessively: Were their ringers on? Did someone have a credit card handy in case funds were low in the detention system’s calling accounts?

One evening when their parents called, Stephanie and her sisters squeezed onto a couch with Joshua. He pulled a guitar onto his lap and began to play “Goodness of God.” On the screen, they watched Nelson and Gladys, clad in jumpsuits, raise their hands in turn and sing as blurred detainees drifted through the background.

For the length of one song played twice, they worshiped as if their parents were in the room.

Photograph by Julian Barreto for Christianity Today.

Photograph by Julian Barreto for Christianity Today.Nothing Nelson and Gladys experienced in detention differs from what is already well documented about life in ICE facilities. Because men and women are held separately, they did not see each other for three weeks—longer, by far, than they had ever been apart in 34 years of marriage.

From California, they were eventually transferred to facilities in Arizona, then Louisiana. For days, depression hijacked Gladys’s senses. For Nelson, it was guilt: He felt responsible for their arrests. In his mind he rehearsed, dreadfully, the possibility of speaking at Stephanie and Joshua’s wedding over Zoom from who knew where.

Frequently Nelson and Gladys could not bring themselves to eat the food served to them, even when they ached with hunger. (“It was, truly, like dog food,” Gladys said.) In Arizona, guards locked Gladys and several other women for 12 hours in a freezing room that reeked of feces and had no working toilet.

Handcuffs were often fastened too tight. “Some people—they just like to torture,” Nelson said. One day, Gladys and another woman wrapped toilet paper around their ankles to ease the pain of rubbing leg irons. A guard stopped them in a corridor and ripped the paper off.

If you believe joy is an act of resistance, in ICE detention you will hazard kindness. Hugging was prohibited; Gladys hugged anyway. She helped women translate paperwork and taught them from the Saddleback curriculum her daughters dictated to her over the phone. In a detention center nurse’s office, Nelson repaired a set of blinds that had been broken for months. He had no ulterior motives. “Nobody can earn anything with good behavior,” he said. “It’s all the mercy of God.”

On Nelson’s first night at the center in Adelanto, he attended a Bible study that convened after the Muslim men wrapped up their evening prayer and cleared the meeting room. He answered detainees’ questions, surprised at how much he could suddenly remember from half a lifetime of reading Scripture.

When he returned the following night, the men asked Nelson if he would lead the group. He opened with an introduction and a confession: He had been involved in his church’s men’s ministry, but not involved enough.

“You know why I’m leading? Because God was asking me almost 10 years ago—even my wife, she was telling me—Why don’t you lead these guys? And I said, ‘I’m busy.’ I thought I was doing enough for God. But I was giving almost nothing to him.”

Over several evenings, Nelson walked the detainees through the story of Joseph in Genesis. He explained how Joseph’s own brothers betrayed him and sent him into bondage, how he was wrongly imprisoned, how in the end God installed him as viceroy of a kingdom.

There was also, unsurprisingly, much prayer. Who could find enough time to pray for every need in a citadel of ruined lives?

A Colombian man asked for prayer before his appointment with an immigration judge. When they next saw him, he was jubilant, hopping up and down. The judge had released him on a $1,500 bail to continue fighting his case from the outside.

The man pulled Nelson into a room and told him quietly that he was a wanted man in Colombia who had done terrible things. I can’t go back, he said. They are going to arrest me.

What Nelson wanted to say: “How unfair. This guy is free in the United States, and I lived a good life and am going back.”

What he actually said: “Do good outside and remember that God loves you.”

The night before ICE transferred Nelson out of Adelanto, he read to the men from Romans 10, about how anyone who says Jesus is Lord and who can believe God would extricate a man from the grave would be saved. Three men kneeled with him and professed faith in Christ.

Deportation was an odyssey all its own. Being woken in the middle of the night—it’s always in the middle of the night—and boarded onto a plane. Landing somewhere in Arizona. Being woken again three days later and loaded onto a bus bound for another airport. Slipping in and out of sleep as the bus sat for seven hours on the tarmac.

After sunup, one of the men roused Nelson and pointed out a group of women boarding the front of the bus, separated from them by a steel mesh partition. Nelson studied the faces filing in, and he just knew: Gladys was among them.

He saw her through the wire grid, her back to him, wearing the same green sweater and heels she’d dressed in the day of their arrest.

Nelson ran to the partition and whispered, “Amorcita.” Sweetheart. When she didn’t turn around, he feared she was mad at him, for everything. He whispered again: “Amorcita.”

This time she spun and saw him. She rushed back and touched her fingertips to his through the mesh. Two minutes later guards pulled the women back off the bus.

Another flight, this time to Louisiana. Three more days in various ICE facilities (“Prisons,” Stephanie calls them). And finally, on March 18, the plane they had never wanted to board could not have been a more welcome sight.

In the final days of his detention, Nelson was lamenting with some other guys that he didn’t know what to do about Stephanie and Joshua’s wedding. He was going to miss it.

Then, on a call, Stephanie came out with a surprise: “Dad, we’re going to get married in Colombia. We’re not going to get married without you guys.”

Nelson cries easily, so just imagine.

The ordeal that Stephanie and Joshua felt at first was “kind of sad”—tossing out months of planning, calling Orange County vendors to cancel, crossing fingers that refunds would come through—turned into the wedding of their dreams.

After frenetic online research, they settled on a location in Medellín, Colombia’s second city but really the darling of nationals and tourists alike. The venue offered its own wedding planner, who pulled together every detail at half the cost of what the couple had budgeted.

And the flowers. In a land that supplies most of the fresh flowers imported by the United States, everything just drowned in them.

Still, when I asked about the guest list, Stephanie and Joshua looked down at their hands. They had absorbed the disappointment of dozens of invitees sending regrets. Travel was expensive, schedules complicated. Crossing international boundaries was dicey now for some guests, who feared getting shut out of the United States if they left.

Nelson and Gladys’s deportation, followed by made-for-television ICE sweeps in Los Angeles, shook Saddleback. The church’s Spanish-speaking congregation in Whittier saw attendance drop by 80 percent, Will Guzman told me.

“All of a sudden it was like, ‘Wow, it happened to them, and they had their life together,’” he said. “ ‘So easily it could happen to me.’”

Stephanie and Joshua flew to Colombia the last week of April—spring break for Stephanie, who now teaches technology at a Christian school in San Juan Capistrano—to visit Nelson and Gladys and scope out the wedding venue.

It was one of several trips the daughters made to Colombia in the months following the deportation. They brought pieces of their parents’ lives in waves of luggage: Clothes and books. Family photos. Gladys’s favorite mug that says, “Jesus Coffee Repeat.”

As the Gonzalezes rebuild from a pile of suitcases, they are doing so in a Bogotá nearly unrecognizable from the one they left behind. Every day is an exercise in relearning their hometown, now doubled in size with as many inhabitants as New York City. Vendors sell arepas beneath LED lamps and soaring glass towers. And when did seemingly every young professional become proficient in English?

One change lights Gladys up: all the churches. The couple emigrated before Latin America’s Protestant explosion, and they never imagined they’d find cristianos, well, everywhere.

Virtually anyone who visits Nelson and Gladys gets an invite to church. Their favorite spot to show off is a megachurch on Bogotá’s north side called El Luger de Su Presencia, where more than 40,000 worshipers cycle through seven services a weekend. “It’s our revival,” Gladys said.

Their dream, they told me recently on a call, is to someday plant a Saddleback satellite in Bogotá. Step one: At their apartment on November 1, they hosted the maiden gathering of their house church.

Photographs by Julian Barreto.

Photographs by Julian Barreto.I visited Nelson and Gladys in Colombia for about a week at the end of July. As they shared hour after hour of their story over coffees and dinner, they never once declined to answer a question about their history. Our last meeting was at the wedding, on my final day there, and it felt as if we were done talking about the past. Now there was only the present.

Nelson escorted Stephanie across a paver patio in golden afternoon light, on a mountainside overlooking the breadth of Medellín, and handed her to Joshua.

Stephanie, stunning and the spitting image of her mother, was in that moment completing a circle Nelson and Gladys began drawing 36 years ago.

Here was the wedding celebration her parents never had—in their native Colombia, swelling with extended family, buoyed by drink and dance and a sense of plenty. It was also in many ways the same wedding as her parents’—full of Californians and talk about God’s design for marriage and a couple working out a future that would span two continents.

Nelson and Gladys played the parts you might expect: a patriarch and matriarch at work. Nelson greeting relatives and friends, surveying the fruit of a lifetime of labor. Gladys laughing and pushing young women, Colombian and American, onto the dance floor for the bouquet toss.

I wondered what strength it required to bear their particular burdens. To know—to be—the reason all these revelers were gathered in Medellín and not in Orange County. Their deportation was no secret; everyone knew. But it was never spoken of, only hinted at, like when Nelson stood to thank everyone for coming to Colombia and could hardly form the words.

Here were the authors of a family, a couple who long ago crossed the threshold of having invested more years in their children than in themselves. And now they were thrust into a new position far sooner than most of their peers: dependency.

Nelson and Gladys were subsisting in Colombia through their savings and the generosity of others—friends who paid their rent, their own daughters who offered help. The logic of it all made no sense to me: In the United States, where they had lived unlawfully, they were taxpayers, spiritual mentors, providers, and essential workers (phlebotomy in California is a critically understaffed profession). Only in their absence were they a drain on America.

If any of that was on their minds at Stephanie and Joshua’s wedding, you would not have known.

The word revelry derives from the same Latin root as rebel—literally, to revolt. Watching Nelson and Gladys at the wedding, it was easy to see them engaging in an act of rebellion. Of refusing to succumb to the weight of consequences or to the wounds inflicted by a nation that has lost its heart for the foreigner.

For a day or two, at least, they chose to be free.

Free to forget that it took them four months to find a landlord in Bogotá who would rent to a couple with no local work history. (“It’s like we don’t exist,” Nelson said.)

To forget about worrying how they will earn a living in a country where newcomers hitting their 60s, with few social connections, do not just catch good jobs in their laps.

To forget they were watching their grandson grow up through a baby monitor app Jessica installed on Gladys’s phone, connected to a camera in a nursery 3,400 miles away.

Tomorrow, Nelson told me, they would resume stepping, one day at a time, into this blank canvas of a new life. He would keep asking God, “If you’ve got a purpose, a plan for us, please, I want to see that soon.”

But that afternoon, Nelson and Gladys simply sat, hands held between them, watching Stephanie take Joshua’s hand and read her vows: “No matter where we are or how far away from home I am, I have realized that you are my home.”

Andy Olsen is senior features writer at Christianity Today.