Some prayers find their way back quickly, like sunlight glancing off water. Others seem to drift into the distance and never return. I have lived in this in-between space, repeating the same words until they grew thin, until they were less speech than breath.

I have prayed for loved ones whose lives were slipping away, sometimes from across the world and sometimes only a few steps away. When they were beyond my ability to hold or help, I found myself grappling with a great sadness. Did God hear my prayers?

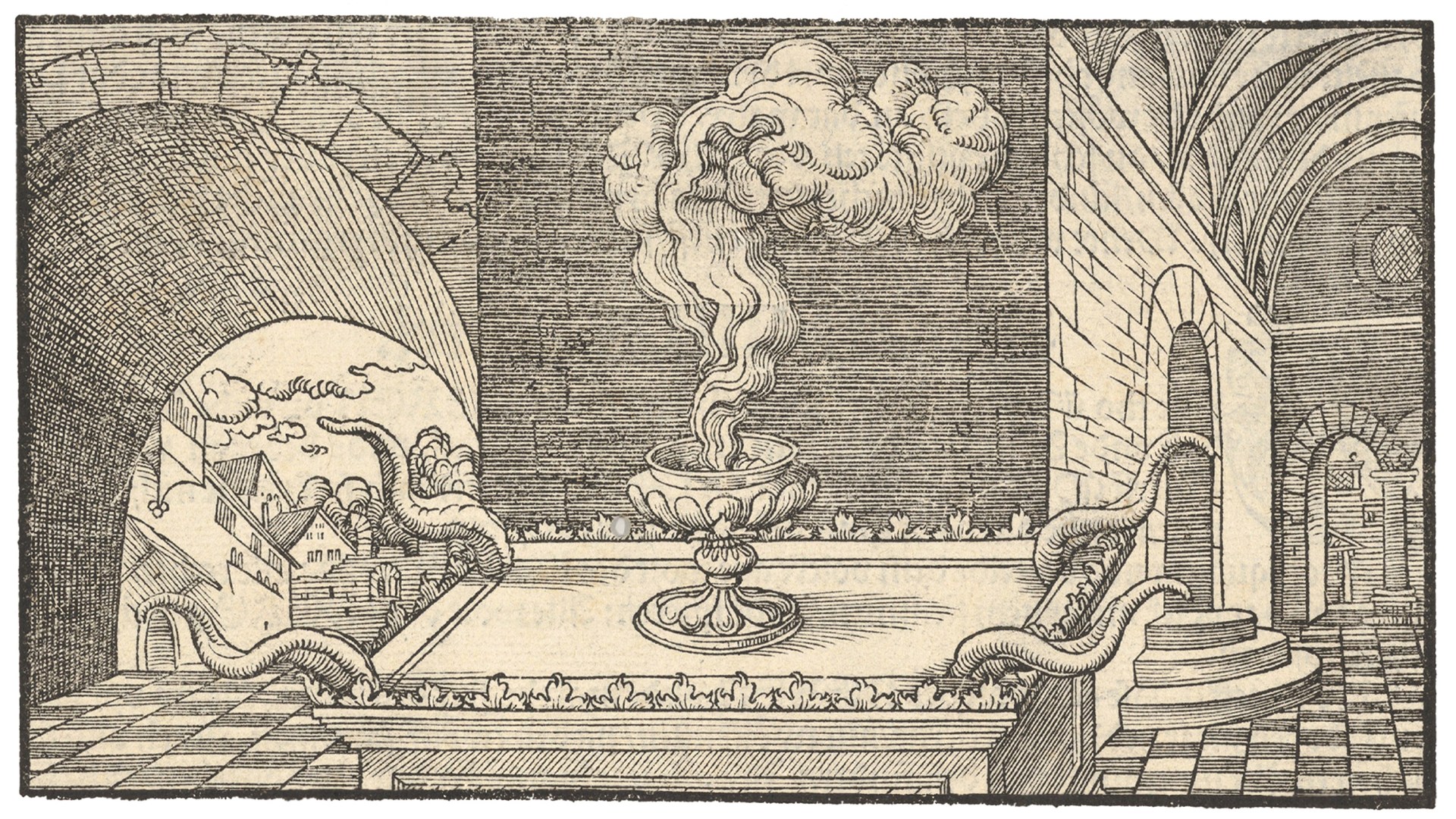

King David struggles with the same question in Psalm 141, imploring God to hear him when he says, “May my prayer be set before you like incense” (v. 2). The Book of Revelation extends this imagery of what our pleas to God look like when John sees the four living creatures and the 24 elders holding golden bowls filled with incense, “the prayers of the saints” (5:8, ESV throughout).

In a time when we do not offer incense to God, why are these Bible verses important? How do they shape and inform our understanding of prayer?

Scripture’s descriptions of prayer as incense are startling in their materiality. Prayer is not an abstract idea but a weighty substance, something offered to God wholeheartedly and with abandon. It rises and fills the spaces we inhabit.

For years, I thought of prayer as sound, something spoken, heard, and gone. I imagined it rising like breath on a winter morning, visible for a moment before dissolving into the cold.

But over time, I began to realize that my prayers did not disappear when the words ended. They seemed to remain, as if silence itself had learned their shape. Even the prayers I never spoke aloud, the ones too tender or confused for words, felt somehow suspended in the air.

Perhaps prayer was never meant to vanish into emptiness but to dwell in the unseen places between our lives and God’s presence, like the smell of sweet incense: invisible, persistent, and real.

Like David and John did, we can come to view prayer as incense, a sacred entreaty to God that rises toward him with the fullness of what we carry. Such a view reminds us that prayer is not a thin gesture but a real offering of our lives before the one who receives us.

The early church carried this vision forward. They understood prayer not merely as a religious symbol but as participation in communion with God. The heart that honors God becomes “an odour of a sweet fragrance,” theologian Clement of Alexandria wrote. Prayer, as Clement said, is an offering shaped not by ritual form but by the orientation of one’s life toward God’s presence.

Yet long before this perspective of prayer as incense became theology, Israel had a living, breathing example of it in the tabernacle.

In the courtyard, where the altar of burnt offering stood, the air would have carried the metallic tang of blood smeared on the horns of the altar (Lev. 4:7) and the acrid smoke of burning flesh. It was the scent of life given, reconciliation made visible.

Inside the Holy Place, priests burned sacred incense—made of aromatics like stacte, onycha, galbanum, and pure frankincense—on the golden altar, using coals from the altar of burnt offering. The golden altar stood before the curtain that hid the ark of the covenant, marking the boundary of the Most Holy Place (Ex. 30:34; Lev. 16:12).

The tabernacle was never perfumed into comfort. Rather, it was thick with life and death. Two scents rose in that sacred space: the sweetness of incense from the inner room and the pungent smell of sacrifice from the courtyard. They burned on separate altars, yet their scents met in the air so that anyone near the tabernacle would breathe both at the same time.

The sharp scents in the tabernacle were not meant to please the senses but to tell the truth: that reconciliation was not a pleasant idea but a costly reality, marked by the smells of what had been burned—not a display of divine cruelty but a way for a broken people to see the cost of restoring what had been broken.

That same rawness still belongs in our prayers. We do not bring perfect words, only what is true: our fears, our failures, our desire to rise again after what has undone us. The God who met Israel in the haze of blood and fire still meets us in our unvarnished petitions and pleas. He doesn’t require us to utter pretty, polished prayers.

We may no longer burn offerings or lift bowls of incense, but our every prayer still begins with the same longing: to be seen, to be forgiven, to be made whole, to be near the God who remembers.

If our prayers are to rise like incense, as David wrote in his psalm, can we be confident that God receives them? Here our hearts often stumble. We pray and wait, and when silence stretches long, we begin to wonder if God has turned away. Perhaps he is distant, disinterested, or displeased with us. Some of us imagine that our unanswered prayers prove his absence.

But the God who receives our prayers is not fickle or forgetful. He is undivided, without shadow or doubleness, unchanging in his faithfulness, sincere in his welcome. As Augustine wrote, “God can be thought about more truly than he can be talked about, and he exists more truly than he can be thought about.”

To pray, then, is not to send words into an empty sky but to entrust them to a Presence who does not turn away, a Presence who keeps listening long after we have stopped speaking, who holds even our silence as part of the conversation.

Even when our petitions falter, when all we can offer is the quiet ache of being alive, our prayers are gathered by the God who does not forget. The distance between heaven and earth is still measured in prayer, where the incense of human longing rises to the God who answers before we call (Isa. 65:24).

We live in an age that wants to perfect even prayer, an age that believes anything can be automated, simulated, or optimized. Artificial intelligence can compose psalms, translate sacred texts, and even mimic devotion in its tone.

But AI cannot ache. It cannot wait. It cannot love the God it addresses. It does not know what it means to live before God with a wounded heart or to hope in a promise not yet fulfilled. It cannot bear the tension of unanswered prayers or learn faith through endurance.

A machine may generate the words of faith but not the life behind them, professor Alastair Roberts wrote for CT. It can replicate the structure of devotion but not the heart that prays. Prayer is not the crafting of words but the offering of ourselves as creatures formed by the Word, Roberts reminds us.

Recognizing that our prayers are like incense to God keeps us embodied, vulnerable, and dependent on him. Prayer is not a task but a relationship, the slow work of love in a world that runs on algorithms and immediate gratification.

When we regard prayer as incense, we develop a keen awareness that it is not a sound that fades but a scent that remains, like smoke that clings to everything it touches. We stay human, imperfect, and alive, reaching toward the God who remembers every quiet supplication we make. Even when words fail, the Spirit himself “intercedes for us with groanings too deep for words” (Rom. 8:26).

Let our prayers rise to God like sweet incense, filling our spaces with the knowledge of his nearness. Some prayers leave the world looking unchanged. Some leave us with questions we carry for years. But they all remake the hearts that pray and reshape the lives woven into these prayers.