The 27 huge dishes of the Very Large Array radio telescope were lined up on interconnected tracks, stretching for miles across the desert Plains of San Agustin in New Mexico. There was little other human activity in sight. My astrophysics colleagues were holed up in the nearby control room, monitoring the data as it came in from halfway across the universe. But I was outside, bundled up against the cold wind, looking up with bare eyes.

The sky was carpeted with stars. Words I had memorized long ago rang through my heart: “The heavens declare the glory of God; the skies proclaim the work of his hands” (Ps. 19:1).

We were using the telescope to hunt for gravitational lenses—places in the universe where space itself is curved. Earthly scales felt insufficient to describe a reality where our sun, for all its size, is but a single grain of sand on the long beach of the universe.

The scale could also be hard for my soul to grasp. As a young researcher, the arguments of atheists sometimes ran through my mind. “We live on an insignificant planet of a humdrum star … tucked away in some forgotten corner” of the universe, astronomer Carl Sagan once wrote. In Western culture, we often assume small means insignificant. So I struggled to grasp the place of humans—and God—in this vast cosmos.

Questions of human significance are arising today in many scientific fields besides astronomy, including cosmology, evolution, genetics, and artificial intelligence. Answers are often couched in atheistic narratives, which in turn have fueled a surge of people claiming no organized religion. Barna surveyed this group of people in 2022, asking what makes them doubt Christian belief. One of the top answers was “science.”

The ideas of scientism and reductionism promoted by some atheists have spread through our culture in recent decades. Science is the best source of knowledge, God is mere superstition, and humans have no higher purpose, they say. In tech circles, the ideologies of techno-salvation and transhumanism are growing as people put their trust in inventions to solve humanity’s problems and conquer death. Though the militant atheists are fading in influence, many in the sciences still reject Christianity as unnecessary or even harmful.

Meanwhile, the church is often seen as having rejected established science or at least not offering useful answers. Current scientific discoveries are only rarely discussed in church. The same Barna study showed most pastors do not realize that science is among the top reasons that people doubt.

We need better narratives than these. To reach people in today’s tech-dominated world, we must bring together the discoveries of modern

science with the ancient truths of Christianity. The coming of Jesus Christ over 2,000 years ago gives powerful answers to today’s questions. If the heavens are unfathomable in their greatness, then this truth is even more stunning: The Creator of the cosmos chose to become incarnate here.

Nasa

NasaWhen God became man, he came to a planet that is but a pinprick in the emptiness of space. In our solar system, the Sun carries the Earth and other planets along as it orbits the Milky Way galaxy, sailing among a vast number of stars of which it is but one.

Astronomers estimate the total number of stars in our galaxy at about 100 billion; the majority are distant and dim, with only a sprinkling of 5,000 or so bright enough to see with the human eye.

Beyond the Milky Way, many more galaxies are scattered along huge filaments throughout space. Some clump together in small groups, like the Milky Way and its neighbor galaxy Andromeda.

Many merge and collide throughout their lives, accumulating mass and birthing new stars. Hundreds or even thousands of galaxies can conglomerate in rich galaxy clusters, which are some of the largest objects known to humans.

The total number of galaxies in the universe is difficult to count, since many are too distant for us to detect. But researchers recently measured the collective faint light of the galaxies and estimated that the visible universe contains hundreds of billions of galaxies—each of which contains billions or trillions of stars.

Most of the stuff in the universe is not stars, however. Data from the WMAP and Planck satellites have shown that 27 percent of the universe is dark matter—a scientific mystery that doesn’t emit or block light and that we can detect only by its gravitational effect on other matter. The greatest part of the universe—68 percent—is dark energy, an even more mysterious substance that drives the way the universe expands.

For all our advances in physics and chemistry, what we know can describe only 5 percent of the universe, including all the stars and all the atoms on the Periodic Table. For the remaining 95 percent, we have no explanation.

Scripture doesn’t mention dark matter or galaxies. Yet the Bible speaks clearly of God’s cosmic scale. In chapter 1 of his gospel, John uses as comprehensive language as possible to talk about what God made. In Colossians 1, Paul proclaims Christ as the Creator of all things. If these first-century apostles had been told about distant galaxies, they no doubt would have declared that those were also created by God.

The Bible’s cosmic claims are timeless, yet they carry more heft when considered alongside the discoveries of modern science. The God who brings out the starry host one by one, calling each by name, can do this for billions upon trillions of stars, not just the few thousand we see at night (Isa. 40:26). The inconceivable vastness of the universe does not diminish God—it shows us more of his greatness.

The place of humans is certainly small; we find ourselves dwarfed by both the creation and the Creator. Yet there’s more to the story. Although he is Lord of the heavens, announcing his coming to earth with a starry sign to the Magi, God also set his heart on humankind. The Creator of the galaxies, eternal and unbegotten, emptied himself and was born as an infant. At the crossroads of time and space, he chose to become fully human, one of us.

That changes everything.

Nasa.

Nasa.The mystery of the Incarnation becomes more profound when we consider the physical aspects. Science has shown that the atoms of our bodies have their origins in the heavens. Hydrogen dates back to the beginning of the universe, when protons formed from cooling primordial plasma. Other elements we need for life—like carbon, nitrogen, and oxygen—arose by nuclear fusion in the cores of stars.

Most of these atoms stay locked in the interiors of stars, but when a star dies in a supernova explosion, the atoms are flung out into space. The explosion is so powerful that additional elements, like cobalt and nickel, form in the expanding shock wave. Astronomers found recently that collisions of neutron stars produce much of the gold and platinum in the universe.

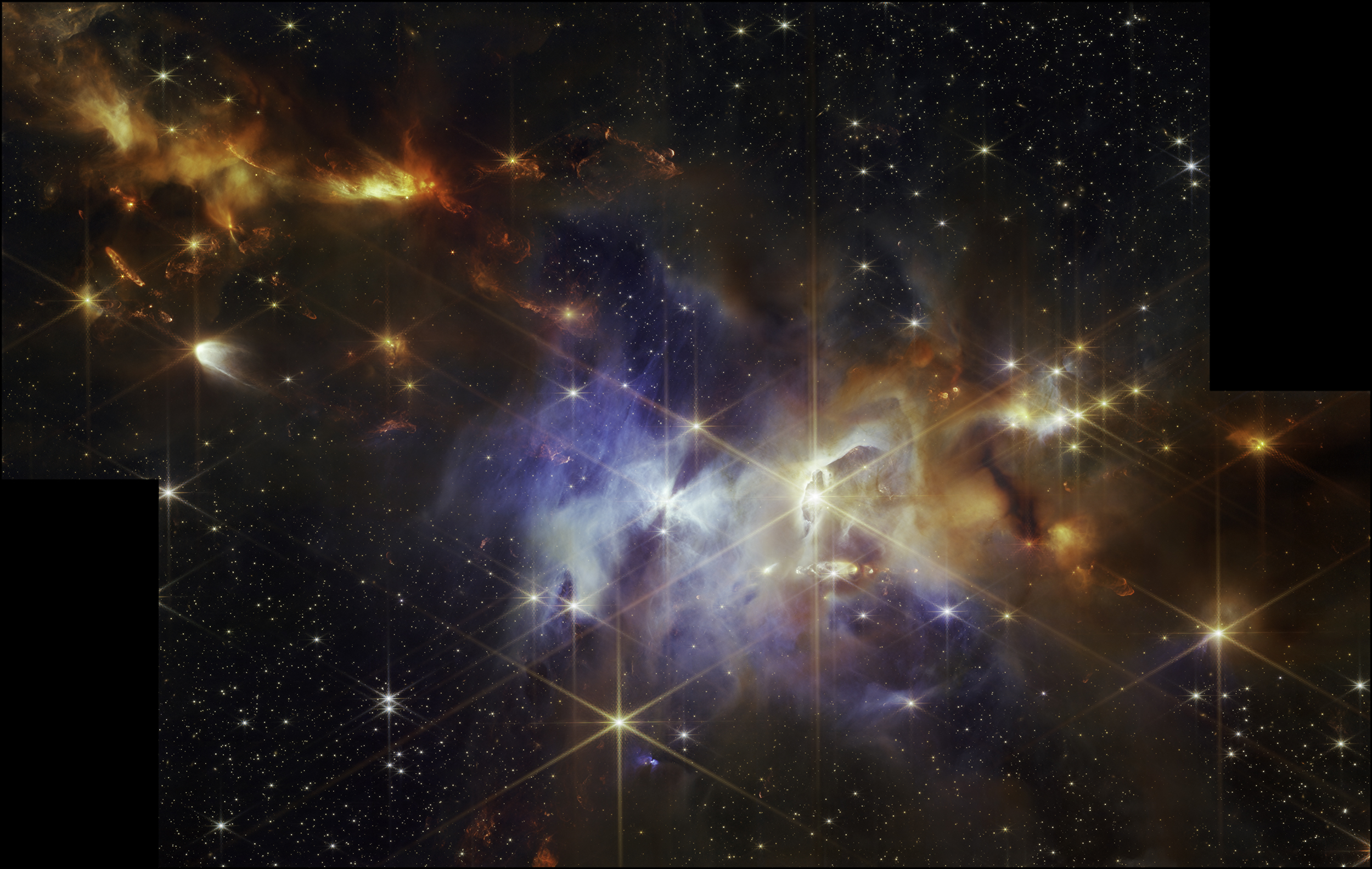

After leaving the stars, these atoms condense into clouds of gas and dust—tiny, clean grains of minerals, hydrocarbons, and ice drifting between the stars like smoke. When nearby stars light up one of these clouds, we see a stunning nebula of brilliant colors and deep shadows.

Some clouds are actually stellar nurseries, where clumps of gas and dust can be dense enough to collapse under their own gravity, eventually leading to nuclear fusion and the birth of a star. The remaining dust stays in orbit around the new star, gradually coalescing into pebbles, then boulders, then moons and planets.

The atoms in our bodies and our planet are indeed, as Carl Sagan put it famously, “star stuff,” or more poetically, stardust. But this means something even more astounding: Through the Incarnation, God himself took on stardust when he took on human flesh.

When Jesus was conceived in Mary, he took on atoms from her—as we all do from our mothers—and those atoms had histories stretching far beyond our solar system. Those atoms assembled into genes to give shape to his bones and blood and into organic chemicals shared with all life on earth.

Each cell of Jesus’ body embodies his love for his creation—not only humans but also the animals, plants, mountains, and rivers often mentioned in Scripture. His very atoms once glowed in beautiful nebulae and powerful supernovae in the far reaches of space. Indeed, when God took on human form, he took on all of creation.

The Incarnation answers deep questions raised by modern astrophysics about our purpose and significance in the universe.

One of the things I love most about astrophysics is the chance to study things that are impossible down on Earth. For example, in Albert Einstein’s theory of general relativity, gravity is defined not as the force described by Isaac Newton but rather as a distortion of the fabric of spacetime. In our everyday lives, Newton’s equations and Einstein’s equations give the same answers, so we don’t notice the difference. But we can see it in galaxy clusters.

Contrary to Newton, who said that light is not affected by gravity, Einstein found that it is. He discovered that space itself is curved and that light follows that curve, changing direction.

In galaxy clusters, the mass is so great that space curves substantially over large distances. An object that curves space this way is called a gravitational lens because—like a piece of warped glass—it distorts what we see through it. The distorted light appears to us as thin arcs circling the foregrounded galaxy cluster, visible in images taken by the James Webb Space Telescope.

Those who study relativity soon learn it is about more than curved space. Relativity describes deep and beautiful symmetries in the cosmos— between space and time, energy and momentum. Moreover, the same laws hold true in every location and circumstance we’ve been able to test. For those who can read the equations, the depth and universality of the mathematics is stunning. Many physicists have thus sensed the divine behind it. In 1948, Einstein himself told his friend William Hermanns, “I meet [God] every day in the harmonious laws which govern the universe. My religion is cosmic.”

Yet that very cosmic harmony can make God seem impersonal. Some years ago, I was out walking and thinking about physics when I suddenly felt overwhelmed by God’s intelligence. It seemed that this immense mind, governing space and time with such precision, couldn’t possibly care about individual people like me. I didn’t doubt God’s existence, but for a season I doubted his love. Einstein felt this too. He also told Hermanns, “My God is too universal to concern himself with the intentions of every human being.”

This is where science falls short. The natural world, though it reveals much of its Creator, cannot give us the full picture. In the Incarnation, we have God’s ultimate answer: Yes, God concerns himself with every human being. We know it because he came in person to dwell among us. The disciples saw him, touched him, knew his smile, and felt his love.

A few months after that walk, the Holy Spirit gradually moved in my heart. God’s love started to seem plausible to me again, but now on an entirely deeper level. I realized that the mind of God is superseded only by the heart of God.

Though the Scriptures don’t speak of galaxies, I found in the Bible a larger framework for understanding the cosmos and its loving Creator. The ancient Hebrew psalmist had little conception of the universe as we know it today. But when he penned Psalm 103, he was referring to the largest thing he could conceive:

He does not treat us

as our sins deserve

or repay us according

to our iniquities.

For as high as the heavens

are above the earth,

so great is his love

for those who fear him;

as far as the east

is from the west,

so far has he removed our transgressions from us. (vv. 10–12)

When the psalmist wrote of the east and the west, the heavens and the earth, he was picturing the furthest extent in each direction. He was pointing to the unfathomable ends of the universe. But he wasn’t doing so to point to God’s intelligence. He was underscoring the profound height and depth of God’s love and forgiveness.

Knowing the expanses of the universe, as we do today, only gives his point greater gravity. Whatever else God is doing in the cosmos, we believe that he took up the atoms of the universe to become one of us. In coming to us as an approachable, helpless baby, God’s message is unmistakable: Do not be afraid. I made you with intention. You are loved.

The carpet of stars above declares the shining glory of God. Yet God revealed his deeper glory, and his very heart, when the Word became flesh—with its cosmic implications—and dwelt among us (John 1:14). Through faith, the astrophysical elements of the Incarnation proclaim the stunning depth of the love of God in the person of Jesus Christ.

The discoveries of science cannot diminish God, for he created it all. Each time we look up at the night sky and consider the stars, we can remember that God delights in reminding us of his love—a love that is wider than the universe.

Deborah Haarsma is an astrophysicist, author, and the former president of BioLogos.