Minneapolis lay under a blanket of snow and single-digit temperatures as parishioners poured into church on a Sunday morning in early December last year. They piled jackets into a coatroom and grabbed cups of strong coffee from the dispenser in the lobby. In the sanctuary of Restoration Anglican Church, vertical stained-glass windows sent shafts of light across the pews.

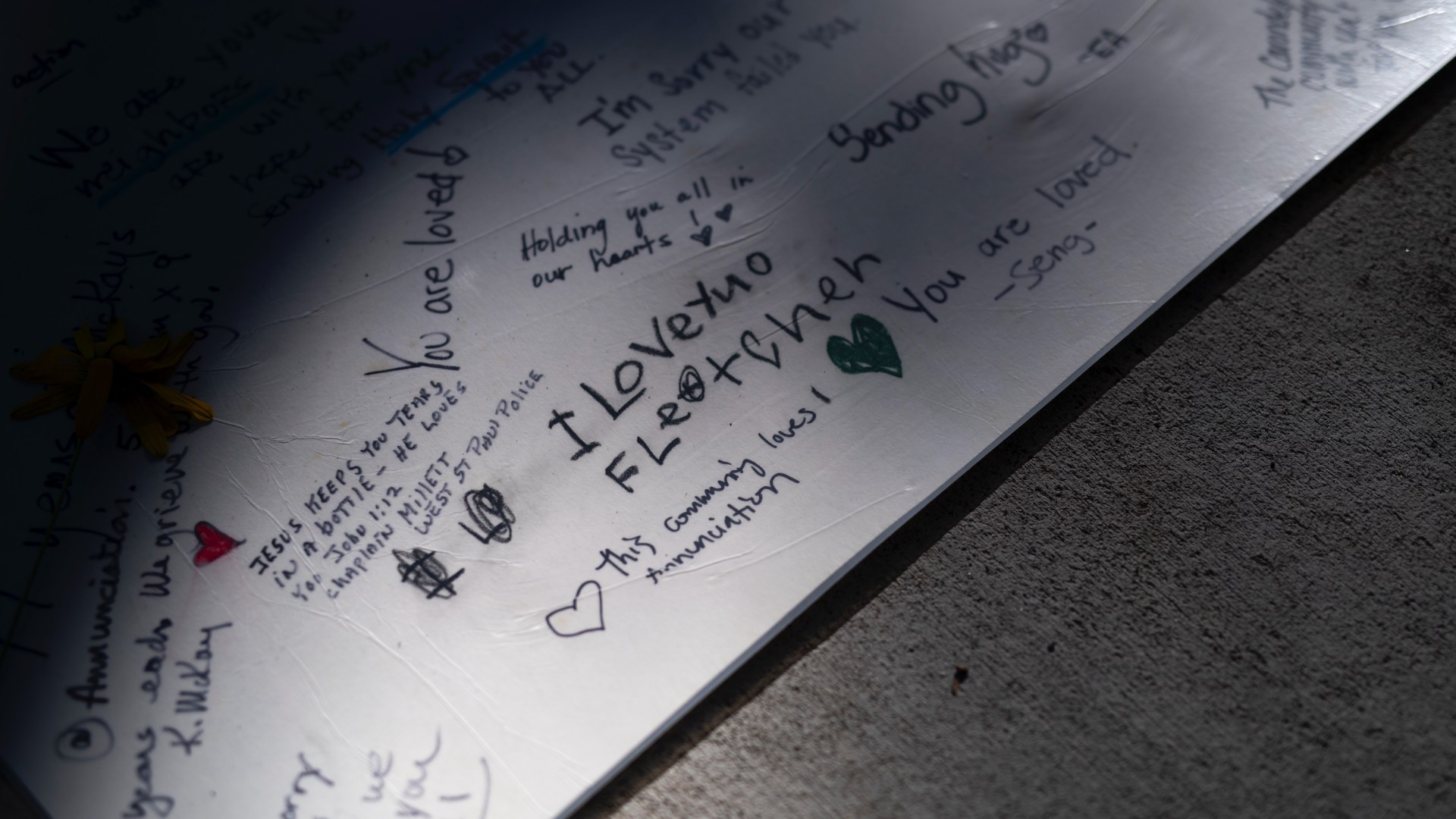

A regular sight in the small balcony next to the organ now is three families, all close friends: the Revells, Holines, and Sharpes. Their children attend Annunciation Catholic School and were there the morning of August 27, 2025, when the student body gathered for the first Mass of the school year and a shooter fired through the sanctuary windows from outside, riddling the Catholic church with 116 bullets. Two students were killed—Fletcher Merkel, 8, and Harper Moyski, 10—and 28 were injured.

In all, six families at Restoration Anglican have children at the school. All survived the shooting unharmed, but they’re dealing with the aftereffects of what one parent likened to a military ambush. Some of the children have nightmares and don’t sleep well. Loud noises or flashing lights or simply being alone can send them into an anxiety tailspin. The parents are fragile too.

The stained-glass windows lining Restoration’s sanctuary are similar enough to those at Annunciation that the children had a hard time returning to church services. So the Sunday after the shooting, Restoration church staff set aside space for the families to worship in the balcony so the kids feel less exposed. For the first few weeks, ministers brought Communion to the families.

Trip Sharpe, 8, who survived the shooting, likes sitting in the balcony.

“Being down there, no,” he told his dad Will Sharpe recently. Why? his dad asked. Trip said he liked just having their family around. Will Sharpe and Mary Marshall Revell are siblings, so some of Trip’s balcony buddies are his cousins.

Trip’s best friend, Fletcher, was killed in the shooting. Trip helped lead a procession at Fletcher’s funeral, holding hands with Fletcher’s brother. Trip’s dad, Will Sharpe, gave a eulogy. Trip can list off his friend’s birthday and tell stories about fishing trips they took together.

Ash Revell, whose big sister Ansley also survived the shooting, zoomed a car over the balcony pews during the service. Nearby was June Holine, a fourth grader who ran with her teacher out of the school during the attack.

June’s little sister Olive, a first grader, also survived. Annunciation has a buddy system for Mass, pairing older students with younger ones—Olive’s buddy laid on top of her during the shooting, then covered her head as they ran out.

The parents still worry in the balcony. Will Sharpe has to pray each service to keep violent images of a potential attack in church from entering his head. His sister, Mary Marshall Revell, struggles with the same thing, her imagination playing over and over what the shooting was like for their kids.

At the front of the sanctuary, two Advent candles were lit, and a child read Isaiah 11:1–10:

The wolf shall dwell with the lamb, and the leopard shall lie down with the young goat, and the calf and the lion and the fattened calf together; and a little child shall lead them. (v. 6, ESV)

“Does God interrupt the chaos of the world?” asked rector Rick Stawarz in his sermon on the passage.

Stawarz and his wife, Molly Stawarz, the pastor of mission at Restoration, had enrolled their 3-year-old, John, at Annunciation’s preschool. When they got word of the shooting, they drove as fast as they could toward the school. They couldn’t get close with all the activity around the school, so they ditched their car and ran, Rick losing his Birkenstock sandals and forgetting to turn off the engine. They found their son and “kissed him like crazy,” Rick said.

John had not been in the sanctuary—he was blessedly oblivious, thanks to a calm teacher who had them play “the quiet game” in their classroom during the attack. As John walked out, he was entranced by all the police and fire trucks; he asked to dress up as a firefighter for Halloween.

America’s ongoing scourge of school shootings not only takes lives but also leaves a pool of surviving children who carry the horror with them. More than 398,000 students have experienced gun violence at school since the Columbine shooting in 1999, according to data compiled by The Washington Post.

Research has shown long-lasting effects on surviving children—like struggling with depression or dropping out of school—but it has also revealed children can be incredibly resilient.

“The field of post-trauma is really big and developing all the time. There is so much we don’t know,” said Anna Mondal, a Christian counselor who specializes in trauma.

The families at Annunciation discovered quickly that there is a national infrastructure to respond to school shootings: trauma centers for children, parental support groups. Organizations showed up in Minneapolis with therapy dogs and bunnies, a big hit with the children.

Annunciation brought in the Washburn Center for Children, a local counseling group, to provide onsite mental health professionals for two school years. As Washburn’s chief clinical officer, Jenny Britton, described to me the close-knit community at Annunciation and how essential that is for trauma recovery, she took a call about an Annunciation student who needed help.

Yet even with all the resources, mass shootings tear an unimaginable hole in a community.

“You keep seeing the fracture continue to spread,” said Will Sharpe, Trip’s dad. Parents of kids in other school shootings have warned Annunciation parents that every step after the event—like deciding whether to reopen the site of the shooting or how to memorialize it—could bring dissension.

“It was pretty shocking … how much it takes to clean up the pieces,” said Emily Collings, who leads the children’s ministry at Restoration and coordinated care for the families of child survivors. She sat in meeting after meeting discussing what to do next: how to support the families, how to navigate kids’ questions in Sunday school, whether to change the classroom locks. One parent asked her about hiring an armed guard.

All of it makes Collings angry at the shooter—such devastation wrought in so few minutes.

But the families at Restoration, taken together, might have something special that could speed their recovery—and help their kids bounce back and understand what happened. These families are seeing the value of close relationships in a trusted faith community in a country where people often suffer individually, out of sight.

Americans are becoming less and less socially connected. As their isolation grows, so do problems with their mental health. But even recovery from crises is often an individual activity with a therapist.

Scientists widely consider social connection one of the strongest predictors of survival at any stage of life. And research on mass shootings has shown that a religious community helps in recovery. The survivors and families at Restoration are learning this—but remaining in community is itself a struggle sometimes.

“Showing up to men’s prayer, showing up to church—showing up has been something that we’re telling ourselves to do. It’s not coming naturally,” said Anders Holine, the dad of June and Olive, who survived. “There are days where I just want to move to the woods and cut ties and be safe.”

But after church events, he said he almost always feels encouraged, renewed. It helps that Restoration’s rector personally understands his family’s terror.

The families say they feel comforted even as they struggle to find meaning in the tragedy.

“You’re not just making sense of it yourself. You’re making sense of it for your kids, who are asking, ‘Why?’” said Anders.

“It’s unnatural, what we experienced,” said Mary Marshall Revell.

Anders Holine and Will Sharpe went to high school together in a Twin Cities suburb but didn’t really know each other. When they were students, Will said, he was getting in trouble while Anders was “pursuing church and making good decisions.” They became friends after Will turned his life around.

Now their families live across the street from each other—a few blocks from Annunciation—and hang out all the time. They walk their kids to school.

Mary Marshall Revell is Will’s sister and also lives less than a five-minute drive away, with her husband, Micah Revell, and their two kids, Ansley, 9, a third grader at Annunciation, and preschooler Ash, 5.

The Holines, Sharpes, and Revells all go to church together. Will and his wife, Kacie, recommended Annunciation to their rector’s family, the Stawarzes.

The day of the shooting, Will and Anders walked their kids to school and then split off. Will went to a grocery store nearby, Anders went home. As Will walked back, he passed the campus. Trip and Fletcher and one of their friends called out to him from a window, laughing. Will laughed too but told them to get back to class. He returned home, took the family dog on a walk, then heard gunshots.

He hopped in the car to get to campus, parked in an alleyway next to school, and ran into the school parking lot. He found an older woman lying on the ground, shot in the leg. Then police came around the corner and told him to get away because they were concerned about a second shooter. Like other parents, he was desperate to find his son. (He knew kindergarteners, including his daughter, didn’t go to Mass.) Trip was in the church, a few rows up from his friend Fletcher.

Anders also heard the gunshots and drove to the school. First responders were just arriving. He saw a police officer come through the church doors with injured children. As the police opened the door, he went into the crime scene to find his girls Olive and June.

But his girls weren’t there. For the parents, the half hour of not knowing their children’s fate was hell. Some kids were hiding under pews. Others had run out at the start of the shooting and were in buildings around the area. They eventually reunited at a gym.

In the chaos of the shooting Ansley Revell, the third grader, tripped and fell over a shoe someone had lost, and then someone stepped on her finger. She got out, and she remembered her friends crying, but parts of her memory are blank.

“I want to remember all of it, but my body won’t let me,” she said, sitting on her couch next to her parents. “I can’t picture it in my mind.”

Ansley remembers that after her parents collected her, an officer checked off her name, noting that she was okay, and her mom and dad said she could have whatever she wanted for lunch. But she felt sick to her stomach and couldn’t eat. She had a popsicle, which helped. The kids may have blocked out the shooting, but they remember the food they ate that day—mostly pizza. Ansley had a smoothie bowl.

After the shooting, the three families piled in at the Sharpes’ house. The kids watched TV downstairs for hours, which they’re not normally allowed to do. The parents sat together upstairs, numb. They stayed at the Sharpes’ house until late. When the parents learned Fletcher had died, they pulled the children aside to tell them.

Ansley immediately went to Trip, knowing he would be upset, and they started talking, said her mom, Mary Marshall. The parents said the children sometimes found it easier to talk to each other about the shooting than to them. But now the kids ask deep questions about it at random times, like on the way to school.

One of Will’s friends came over the night of the shooting. They sat on the front steps, and Will cried, the first time he let himself lose it. Micah Revell lost it in his kitchen after he put his kids to bed. Micah’s dad, John Revell, got into full-time police chaplaincy in 2012, ministering to first responders in Newtown, Connecticut, who struggled after the Sandy Hook shooting.

The evening of the shooting, Restoration held a prayer vigil. After that, the three families said they ate more meals together than not, sometimes with the Stawarzes as well. They didn’t wallow in feelings about the shooting—sometimes they were just hanging out—but these times were a relief when other people either avoided talking about the event or wanted to move on quickly.

“Having the ability to process and talk through with each other was such a gift from God,” said Will.

Britton, from the children’s trauma counseling group, said well-meaning people often ask questions like “How are you doing?,” which can sometimes feel hard to answer, especially for kids. Instead she suggests having a normal conversation that is not about their recovery, like “I am so happy to see you today. I heard you joined the basketball team.”

The day after the shooting was Ansley’s birthday. Collings, the children’s pastor, pulled together a birthday gift and care package.

“Everyone’s like, ‘Oh my gosh, that must have been a horrible birthday.’It was a pretty good one,” said Ansley.

Restoration started a meal train for the families. Anders discovered there were skilled sourdough bread bakers in the church after several delicious homemade loaves showed up at his home.

“They had already, within a very short amount of time, thought through all of these ways to care for us so that we didn’t have to think of those things,” said Mary Marshall.

Will was asked to do a eulogy for Fletcher’s funeral. He processed it with his counselor and then with Rick Stawarz and prayed every morning for the right thing to say. He felt intimidated by the glare of attention. What came to him was Psalm 23: “I lack nothing” (v. 1). He clung to it. At the Restoration service before the funeral, Stawarz anointed him with oil. People laid hands on him and prayed.

Will had coached Fletcher in soccer, football, and basketball. In the eulogy he talked about the gift of being welcomed into the Merkels’ circle, then told the family, “We are here for you, and we are not going anywhere.”

He quoted 1 Corinthians 15 and said, “Because of Jesus, death has had no victory over Fletcher. … He is safe. He made it to his heavenly home, and boy do we miss him.”

After the funeral, the Sharpes, Revells, and Holines ate dinner together. By the end of the evening, they were even laughing.

“I remember looking around and thinking, Okay, this is how we’re going to survive this. Because we have this,” said Mary Marshall.

Courtesy of Anders Holine

Courtesy of Anders HolineBefore the shooting, Micah Revell said the three sets of parents were struggling with some level of numbness with their faith. Now church is what brings out his emotions, even if he has felt disconnected during the week. Communion especially feels like “tangible comfort,” said Micah. “This really is the physical presence of Jesus.” The parents all brought up falling back on the sacraments and liturgy of the Anglican tradition.

Discussion of sorrow and suffering is “built into the way that the Anglican church, or our church, approaches daily life and the world,” said Sharpe, who is new to Anglicanism. The Holines and Sharpes weren’t at Restoration a year before the shooting, but Mary Marshall feels they were all drawn together into the same church as a gift.

“Church has always been really hard for me … for most of my life,” said Mary Marshall, mentioning some hurtful experiences at recent churches. But the time her family has been at Restoration has been “life-giving and healing,” she said. “Their response and their care for us—it couldn’t have been more different.”

Molly Stawarz said the Anglican tradition places a high value on kids’ involvement in church because of the belief that they can have a relationship with God—and, Rick Stawarz added, they can practice spiritual disciplines.

“This is a place where their kids are being given the space to process this—not just individually but to process it liturgically,” said Rick. “Whether they realize it or not, they’re being connected to the weekly rhythms of our church and the prayers of our church.”

In September, about two weeks after the shooting, June and Trip were scheduled to be baptized at Restoration. They both wanted to go forward with it. Usually the Anglican tradition does sprinkling baptism, but many in the congregation come from Baptist backgrounds, so the church does full immersion, too, which is what the kids did. June wore an Annunciation T-shirt. Anders told himself to keep it together as he watched, going into a sanctuary for the first time since the shooting.

“It’s the very basics of Christianity that I really should have practiced—fundamentally trusting God with your future, trusting the unknowns, entrusting your kids’ lives,” said Anders. “Am I really doing that? I’d rather have safe circumstances and just be safe physically. The Bible is really challenging. … I can’t pave my own road.”

Anders said June dried off from the baptism, they ate a quick lunch, and they went to Harper Moyski’s funeral.

Rick reflected on the baptisms later: “Yes, be reminded that by Christ’s death and resurrection, you are united to him, and nothing can separate you from him. You are claimed by him, united with him, and received into the household of God, which is both a local church reality, but it’s also this heavenly, cosmic reality as well. You belong to Jesus.”

But the parents still discover unexpected “pockets of pain,” as Will described it. The power flickered in the Revells’ house recently, and Ansley sprinted to Mary Marshall, screaming. Mary Marshall just held her. Ansley’s whole body was shaking.

“She has a really good game face, and I do believe she’s sharing with us, but there’s a lot more going on inside,” said Mary Marshall. The therapist the Revells see told them they didn’t need to rush her into therapy but should wait until she is ready—advice echoed by other therapists CT interviewed.

June Holine sleeps with her Bernedoodle sometimes because nights are hard now. She said if she could, she would have 50 dogs, and then she could crowd-surf on them.

“To have those friendships in place with these friends that are also at their church, and then the broader church community that we have, is going to be really good for Ans,” said Micah.

The Anglican families have felt cared for by the Catholic community at Annunciation, too. The parents go to a weekly meeting with other Annunciation parents at a local pizza place, where they’re forming a parents advocacy group that, among other things, is looking at pushing gun reforms. “The grief and helplessness is getting channeled into ‘Okay, what can we do?,’” said Mary Marshall.

One snowy night in December, Beth Holine, Anders’s wife, proposed to the parents a name and mission for their nonpartisan advocacy organization. Anders was watching their girls at home and followed the meeting on Zoom, and the Revells squished behind a table with other parents. The room was packed, and the floors were wet from snowmelt.

“I would love for there to be some kind of broader Christian response that can really make a change in our country,” said Molly later about the gun debate. “We are uniquely equipped to enter these incredibly difficult dialogues.”

Life goes on, with sports, parent meetings, and birthday parties, but the shooting comes up. When June’s basketball team lost recently, the winning team gave them bracelets as consolation because they were from Annunciation.

Recently, the Sharpe, Revell, and Holine children went back into the Annunciation sanctuary for the first time since the shooting. The parents noticed that June, Trip, Olive, and Ansley wandered to the choir loft on their own and prayed for the families of Fletcher and Harper.

Meanwhile, Restoration’s worship director, Derek Boemler, and another church musician, Chris Gisler, released a new worship song for their church that they wrote in response to the events:

“There is a refuge in your wings

A help in troubled times

You cause the broken heart to sing

And you’re singing now in mine.

“May I know the Comforter

May I know the God of peace

May I know the one who holds the stars

Is holding on to me.”

“The One Who Holds the Stars,” courtesy of Derek Boemler: