This piece was adapted from CT’s books newsletter. Subscribe here.

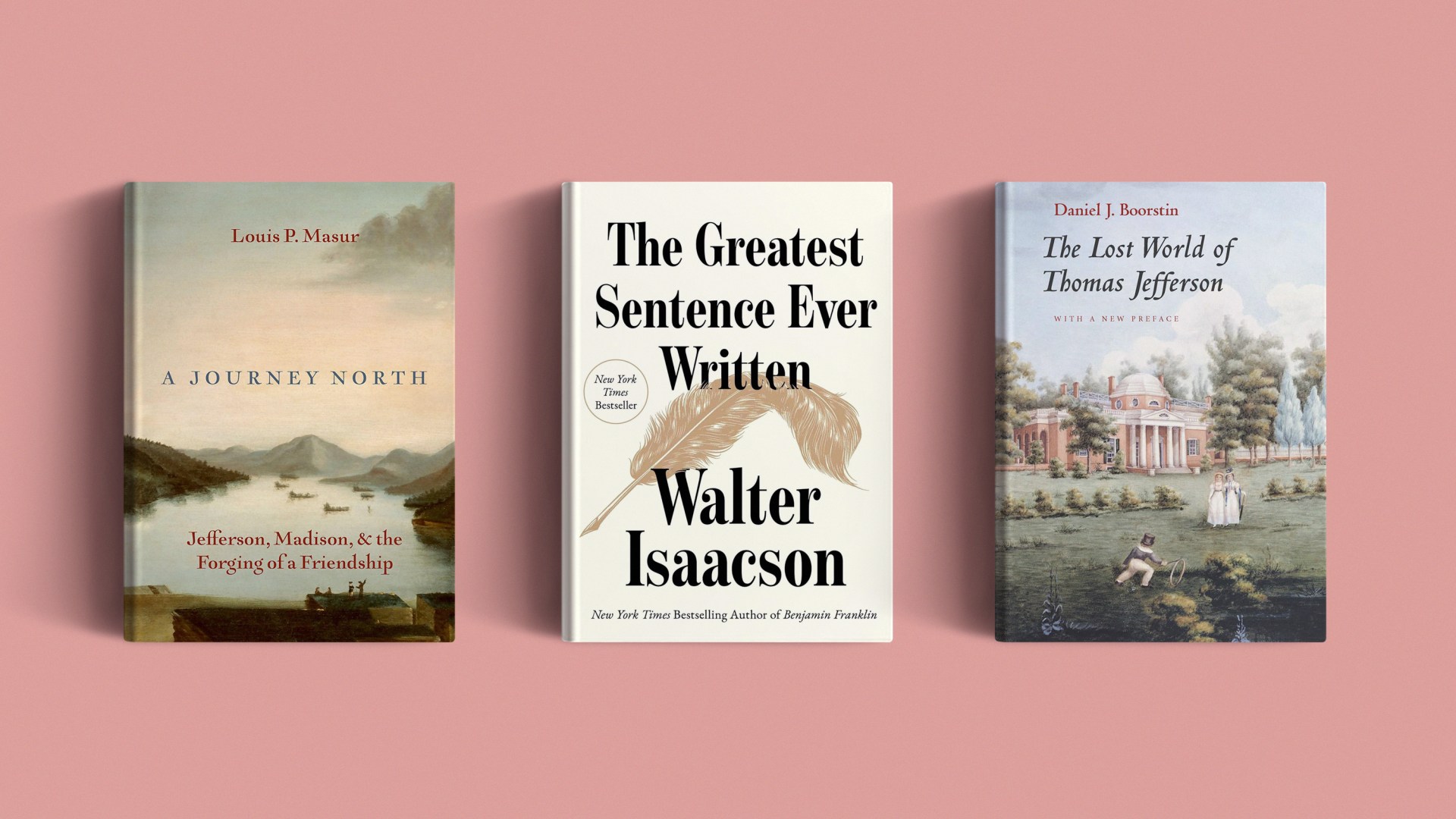

Walter Isaacson, The Greatest Sentence Ever Written (Simon & Schuster, 2025)

Walter Isaacson’s brief book The Greatest Sentence Ever Written marks America’s 250th birthday by considering the Declaration of Independence’s second sentence and its “self-evident truths” of equal rights by God’s endowment. The Greatest Sentence is a great concept for a book, focusing on an undeniably great sentence. But the book doesn’t live up to its potential.

Isaacson, the author of popular biographies, including one on Benjamin Franklin, gives surprisingly sparse attention to what the declaration’s second sentence actually says. Instead, he is mainly concerned with using the sentence to offer anodyne comments about American capitalism needing communitarian constraints. Many Christians would agree with him about how a free society also must inculcate care for one’s neighbors.

But Isaacson seems ambivalent about the second sentence’s invocation of God’s created order as the basis for human equality. On the book’s first page, Isaacson claims that the Declaration based fundamental human rights “on reason, not the dictates or dogma of religion.”

In the next sentence, however, Isaacson acknowledges that Jefferson and his composition committee (including Franklin and John Adams) asserted that God created us equal and endowed us with fundamental rights. Isaacson assumes but does not demonstrate that Jefferson wouldn’t have explained the grounds of our rights in religious terms. He speculates that John Adams suggested the “endowed by their Creator” phrase.

Louis P. Masur, A Journey North: Jefferson, Madison, and the Forging of a Friendship (Oxford University Press, 2025).

More rewarding than Isaacson’s book is Louis P. Masur’s gem A Journey North: Jefferson, Madison, and the Forging of a Friendship. This book is a microhistory of Jefferson and Madison’s six-week trip in 1791 to the northern states, which solidified the Virginians’ friendship and political alliance for the next 35 years.

The six-week journey itself doesn’t yield much source material. But Masur imaginatively uses highlights of the trip to illumine Madison and Jefferson’s views on topics such as science, race, and language.

The men’s Federalist opponents swore that Jefferson and Madison were in the north to bolster the incipient Democratic-Republican Party. (New England was the nation’s stronghold for the Federalist Party of George Washington, John Adams, and Alexander Hamilton.) Masur insists that the trip was not primarily political but was for “health, recreation, and curiosity,” as Madison put it.

Madison and Jefferson fished, hunted, and studied plants and trees. They stayed at dozens of inns, which Jefferson diligently rated in his journals. (He would have loved posting Google Reviews.)

Masur is fully aware of the men’s failings, especially regarding slavery. He represents these founders as the curious, humane, and imperfect people they were. They were admirably capable of learning. Jefferson, as on many scholarly topics, became nearly obsessed with the science behind New England’s sugar maples. He tried to grow them in Virginia for decades; alas, the climate there was too warm.

One of their most fascinating encounters was with Black farmer Prince Taylor of Fort George, New York. Taylor, a Continental Army veteran, owned a 250-acre farm “which he cultivates with 6 white hirelings … and by his industry and good management turns to good account,” Madison noted. Such an arrangement of Black ownership and white labor would have been incomprehensible in Virginia. Madison didn’t comment further on Taylor, but the experience reminded the slaveholders that the principles bolstering Virginia plantation slavery did not hold true everywhere, even in the America of 1791.

Daniel J. Boorstin, The Lost World of Thomas Jefferson (Beacon Press, 1948)

Daniel J. Boorstin’s classic book The Lost World of Thomas Jefferson helps us fathom the cosmology that lay underneath Jefferson and Madison’s curiosity about sugar maples. Boorstin, a historian and librarian of Congress, mapped Jefferson’s intellectual world and those of colleagues affiliated with the American Philosophical Society (APS), which Jefferson served as president. These associates included the radical democrat and skeptic Thomas Paine and the English Unitarian minister and scientist Joseph Priestley. Priestley’s writings on Unitarianism profoundly influenced Jefferson’s mature religious views.

Boorstin shows that Jefferson and his APS circle viewed God as the “Supreme Maker” and the great “Architect and Builder” of the world. Jefferson’s views about nature and political rights depended on a created order. While his specific beliefs (including his denial of the Trinity) contradicted the great tradition of Christian theology, Jefferson could never dispense with the eternal God as the creative force behind the observable world.

Whether discussing human equality or botanical science, Jefferson assumed that nature operated according to predictable rules and that a rational Creator stood behind those rules. Jefferson thus doubted specific Christian doctrines, but his views of creation were conventional among Americans of the founding generation.

Thomas S. Kidd is research professor of church history at Midwestern Baptist Theological Seminary.