This piece was adapted from CT’s books newsletter. Subscribe here.

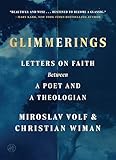

Miroslav Volf and Christian Wiman, Glimmerings: Letters on Faith between a Poet and a Theologian (Harper One, 2026)

Glimmerings: Letters on Faith between a Poet and a Theologian offers a welcome reprieve from polarizing discourse, modeling a healthy approach to disagreements concerning God, prayer, faith, and Holy Writ. The book’s curated email thread between professors Chris Wiman and Miroslav Volf exemplifies Paul’s calls to build up and honor one another above ourselves.

Dissent here does not division make. Towards the book’s end, Wiman cites a letter two centuries old in which fellow poet John Keats proposes negative capability as the mark of a great writer—the willingness to remain “in uncertainties, mysteries, doubts, without any irritable reaching after fact and reason.” Wiman embraces poetry that “remains perpetually open,” particularly verse alluding to the divine. But he trips up at Scripture that demands similar interpretive flexibility—what many Bible readers treat as metaphor, symbol, or indecipherable mystery.

The nature of Christ’s death, Paul’s revivifying Eutychus, the parable of the talents, Christ’s cursing of the fig tree, and Mark’s final 12 verses present Wiman with unsolvable riddles that stymie rather than stoke his faith. Like Keats, he finds constructed and conflicting features of Scripture evidence of errancy, yet he confesses the daily, ineluctable draw of the Jesus drawn in its pages.

Volf’s learned yet equally vulnerable responses provide a master class in compassion. Instead of approaching their dialogue as an argument, he commiserates and highlights common ground when possible, walking alongside a good friend in spirit when conflicting schedules have upended their regular joint strolls around campus.

Crystal L. Downing, The Wages of Cinema: A Christian Aesthetic of Film in Conversation with Dorothy L. Sayers (InterVarsity Press, 2025)

Like Salvation from Cinema (2015), the title of Crystal L. Downing’s new book, The Wages of Cinema: A Christian Aesthetic of Film in Conversation with Dorothy L. Sayers, shows her ongoing effort to challenge criticisms of film that ignore artistry to mostly focus on rejecting questionable content.

Concerned that viewers who generate lists of objectionable material unwittingly blind themselves to the truth and beauty of a film, she enlists mid-20th-century detective writer Dorothy Sayers to build a case for examining the painstaking craft of cinema.

With the help of Wheaton College’s voluminous archives on Sayers, Downing traces the writer’s use of cinematic technique and device in the fiction and plays that followed her brief stint as a screenwriter, spotlighting a persistent attention to style and structure that mirrors the believer’s appreciation of an exquisite, if broken, creation.

Spotlighting the “both/and thinking” that declares Jesus simultaneously fully God and fully human, Downing heralds films like The Bridge on the River Kwai, which leave character motivation shadowed by ambiguity, problematize binary distinctions between good and evil, and encourage viewer identification with the villain’s familiar need for forgiveness.

Similarly, she prefers the satiric role reversals of the Barbie movie, which critique the objectifying gaze of male desire by making Ken, not Barbie, the one whose confidence crumbles when not propped up by another’s flattering attentions. Titles like Romancing the Stone that redefine virtue as a function of gendered beauty and brawn receive a much-deserved kick in the pants.

Mary Shelley, The Last Man (1826)

In the decade that passed between conceiving Frankenstein and publishing the apocalyptic The Last Man, Mary Shelley suffered the loss of three children, her husband, and a very good friend. Her first and most famous novel, written as a teenager, was shaped by the absence of a mother she never knew and the death of a prematurely born child, spawning the horror of an inexorable force whom neither reason nor careful planning could forestall.

When she later imagined a global pandemic that decimates the human race, she drew from a far deeper well of anguish filled with dysentery, malaria, miscarriage, fatal fevers, and a sudden drowning at sea. Her third novel, which celebrates its bicentenary this year, provided Shelley the same occasion it offers the novel’s frame narrator—and which it supplied my students during the COVID-19 lockdown: the opportunity to temper “real sorrows and endless regrets by clothing these fictitious ones in that ideality which takes the sting from pain.”

Recreating a past peopled with deceased loved ones in this biographical roman à clef (“novel with a key”) allowed Shelley to process her loss. She reimagines her broken circle of friends and family as a tightly knit community whose members take great risks for one another as the world ends. Shelley’s framing of wide-scale catastrophe registers the agony of loss but simultaneously recommends a heartening rejection of despair that holds, as its titular character does, to “the visible laws of the invisible God.”

Paul Marchbanks is a professor of literature and film at California Polytechnic State University. His YouTube channel is “Digging in the Dirt.”