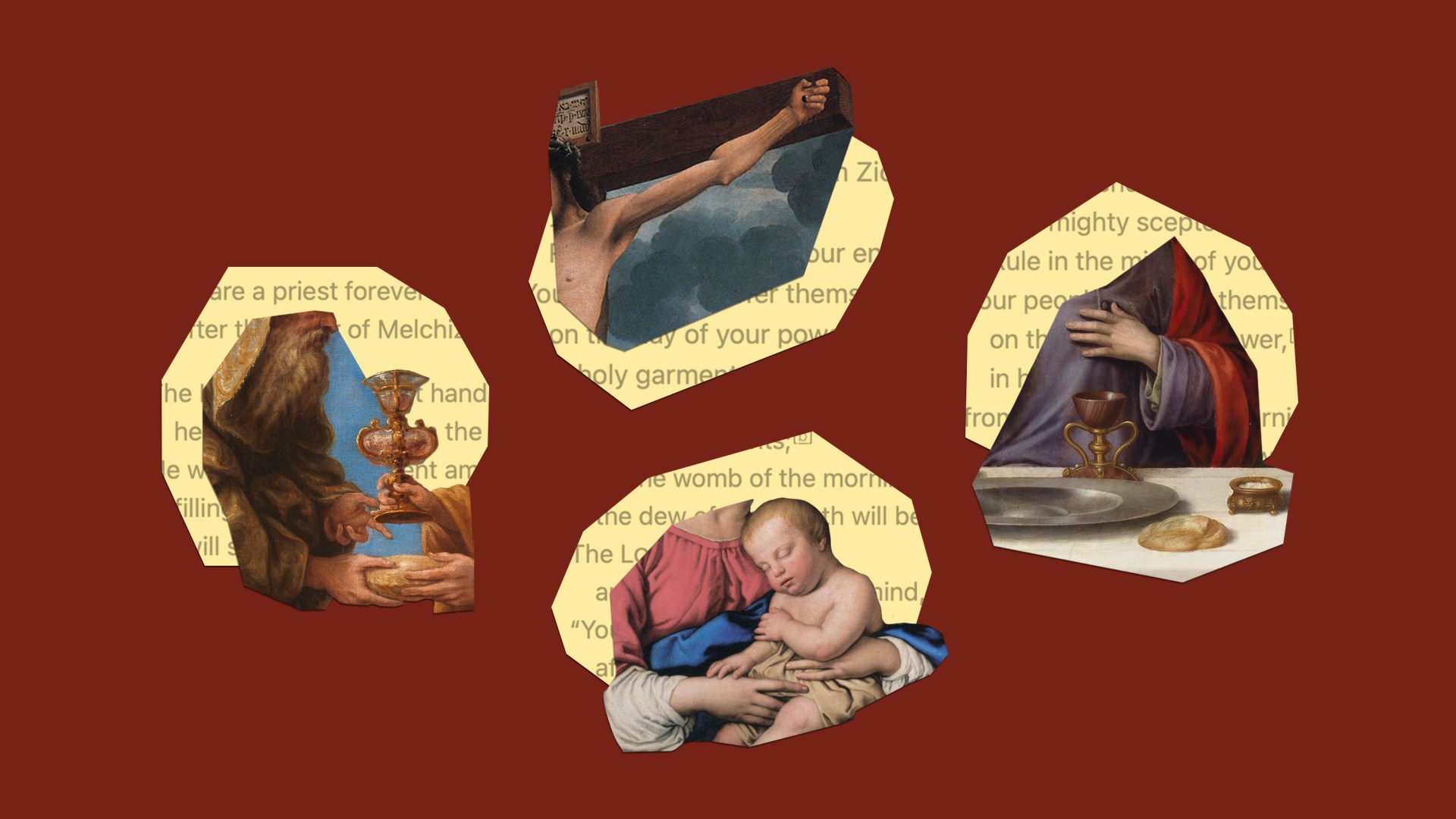

The Hebrew Bible does not contain a formal creed or systemization of core doctrines, but if it did, it might be Psalm 110. Martin Luther called it “the very core and quintessence of the whole Scripture,” and there is no Old Testament text more quoted or alluded to in the New Testament.

In just seven verses, we find miniature versions of Christian doctrines including the Trinity, the Incarnation, the inspiration of Scripture, the humanity and divinity of Christ, the holiness and unity of the church, and the ministry of Jesus as prophesied Priest and King. The British philosopher A. N. Whitehead famously described European philosophy as a series of footnotes to Plato. We could say something similar: New Testament theology is a series of footnotes to Psalm 110.

Here is the psalm in its entirety (ESV here and throughout):

The LORD says to my Lord:

“Sit at my right hand;

until I make your enemies your footstool.”

The LORD sends forth from Zion

your mighty scepter.

Rule in the midst of your enemies!

Your people will offer themselves freely

on the day of your power,

in holy garments;

from the womb of the morning,

the dew of your youth will be yours.

The LORD has sworn

and will not change his mind,

“You are a priest forever

after the order of Melchizedek.”

The Lord is at your right hand;

he will shatter kings on the day of his wrath.

He will execute judgment among the nations,

filling them with corpses;

he will shatter chiefs

over the wide earth.

He will drink from the brook by the way;

therefore he will lift up his head.

Psalm 110 is like a classic song everyone keeps singing. Jesus, his disciples, and the apostles all quote Psalm 110. For Jesus, Psalm 110 is quite literally a conversation-stopper, a trump card that he plays to silence those who reject his claims. He quotes the first verse and asks the Pharisees: “‘If then David calls him Lord, how is he his son?’ And no one was able to answer him a word, nor from that day did anyone dare to ask him any more questions” (Matt. 22:45–46).

Peter makes Psalm 110 the biblical punchline of his Pentecost sermon (Acts 2:34–36), then does the same thing a short while later in debate with the Jewish council (5:31). Stephen alludes to it as he is about to be stoned (7:56). Paul evokes it frequently, often at crucial moments in his reasoning (Rom. 8:34; 1 Cor. 15:25–27; Eph. 1:20; Col. 3:1). The argument of Hebrews is built on it from start to finish (1:3; 4:14–5:10; 10:11–14; 12:2). It turns up in 1 Peter 3:22 and Revelation 3:21; 19:11–21. It even makes an appearance in the Apostles’ Creed.

The New Testament’s emphasis on Psalm 110 may be puzzling. How did this little poem become so central to Christian thought and doctrine from the very beginning? What do we do with all the Iron Age details we find difficult—dew from the womb of the morning, a priest after the order of Melchizedek, the shattering of kings and the strewing of corpses? And why was this psalm in particular—this psalm that most of us never sing and many of us struggle to understand—so significant to Christ and the apostles?

Much of the answer is found in that magnificent opening verse.

A Psalm of David.

The LORD says to my Lord:

“Sit at my right hand,

until I make your enemies your footstool.”

Jesus, as we have seen, bamboozles the Pharisees with the implications here. If David refers to the Christ as his “Lord,” who sits at the right hand of God with his enemies under his feet, then David surely cannot be referring to a mere human descendant. And if (as the Gospels clearly indicate) Jesus himself is the Christ, and therefore the “Lord” of Psalm 110, then it is hard to escape the conclusion that he is a divine as well as a human figure. As C. S. Lewis put it, by quoting the opening verse in the way that he did, Jesus “was in fact hinting at the mystery of the Incarnation by pointing out a difficulty which only it could solve.”

The psalm goes even further than pointing to Jesus’ divine nature. The opening verse contains not just two characters, but three: “the LORD,” “my Lord,” and the speaker. But if the speaker is “David himself, in the Holy Spirit,” as Jesus puts it, then we have a remarkably clear reference to the Trinity (Mark 12:36). The Spirit is telling us what the Father says to the Son. The intimacy here, as we eavesdrop on conversations between the divine persons, is breathtaking.

Indeed, we may be able to go further still: The psalm references the eternal “begetting” of the Son. If we assume that the person being addressed in verses 1–4 is the Christ/Lord throughout, which seems almost certain, then Christ is promised a global kingdom, daily refreshment, and an everlasting priesthood. The Greek version adds even more fuel to the theological fire: “From the womb, before the dawn-bearing morning star appeared, I begot you” (v. 3, LXX). When you read this alongside Psalm 2, as the early church did, it sounds suspiciously like a statement of the eternal generation (or “begetting”) of the Son.

However, the most dramatic move in the psalm is where the Messiah is identified as a priest. Davidic kings came from the tribe of Judah; priests came from the tribe of Levi. It would be slightly anachronistic to refer to this as a separation of powers within Israel, but only slightly. Yet David is unapologetic:

The LORD has sworn

and will not change his mind,

“You are a priest forever

after the order of Melchizedek.”

This astonishing verse reaches a thousand years backward to the mysterious priest-king Melchizedek who blessed Abram (Gen. 14) and reaches a thousand years forward to the New Testament’s most theologically sophisticated argument (Heb. 7–10). God promised Christ that he would be a priest. And not just any priest: an everlasting, Melchizedekian priest rather than a temporary, Levitical one.

If we read Psalm 110 carefully, Hebrews argues, we know that Christ comes as a priest who is greater than Abraham, qualified by his indestructible life, the source of a better hope and a better covenant than the old ones, able to save us to the uttermost because he always lives to pray for us, and perfect forever (7:4–28). Few doctrines in Scripture are more comforting than the fact that the all-conquering Lord of the world is blameless, indestructible, and permanently praying for you—and that comfort is entirely drawn from an exposition of Psalm 110.

Psalm 110 also provides the basis for a beautiful doctrine of the church:

Your people will offer themselves freely

on the day of your power,

in holy garments. (v. 3)

Here, the people of God are drawn freely to Christ’s sovereignty, rather than coerced or commandeered, and dressed in clothes of priestly holiness. When Christ the royal priest rides out to battle, he is accompanied by a royal priesthood in his train: his church. The comprehensive victory that he wins over the powers and rulers—with nations judged, kings shattered, and chiefs scattered—becomes ours. So, presumably, do the rest and refreshment that come in the final verse:

He will drink from the brook by the way;

therefore he will lift up his head.

These are deep scriptural waters. In just 70 Hebrew words, we are pointed toward the Father Almighty, Jesus Christ his only begotten Son our Lord, the Holy Spirit who spoke by the prophets, and the holy church. We find humanity and divinity, incarnation and exaltation, kingdom and priesthood, victory and sacrifice. Convictions on which our faith depends, from the Trinitarian nature of God to the inspiration of Scripture and the intercession of Christ, are littered throughout this psalm. Joy bubbles forth from it. Given that we will be singing this psalm forever, we might as well start now.

Andrew Wilson is teaching pastor at King’s Church London and author of Remaking the World: How 1776 Created the Post-Christian West.