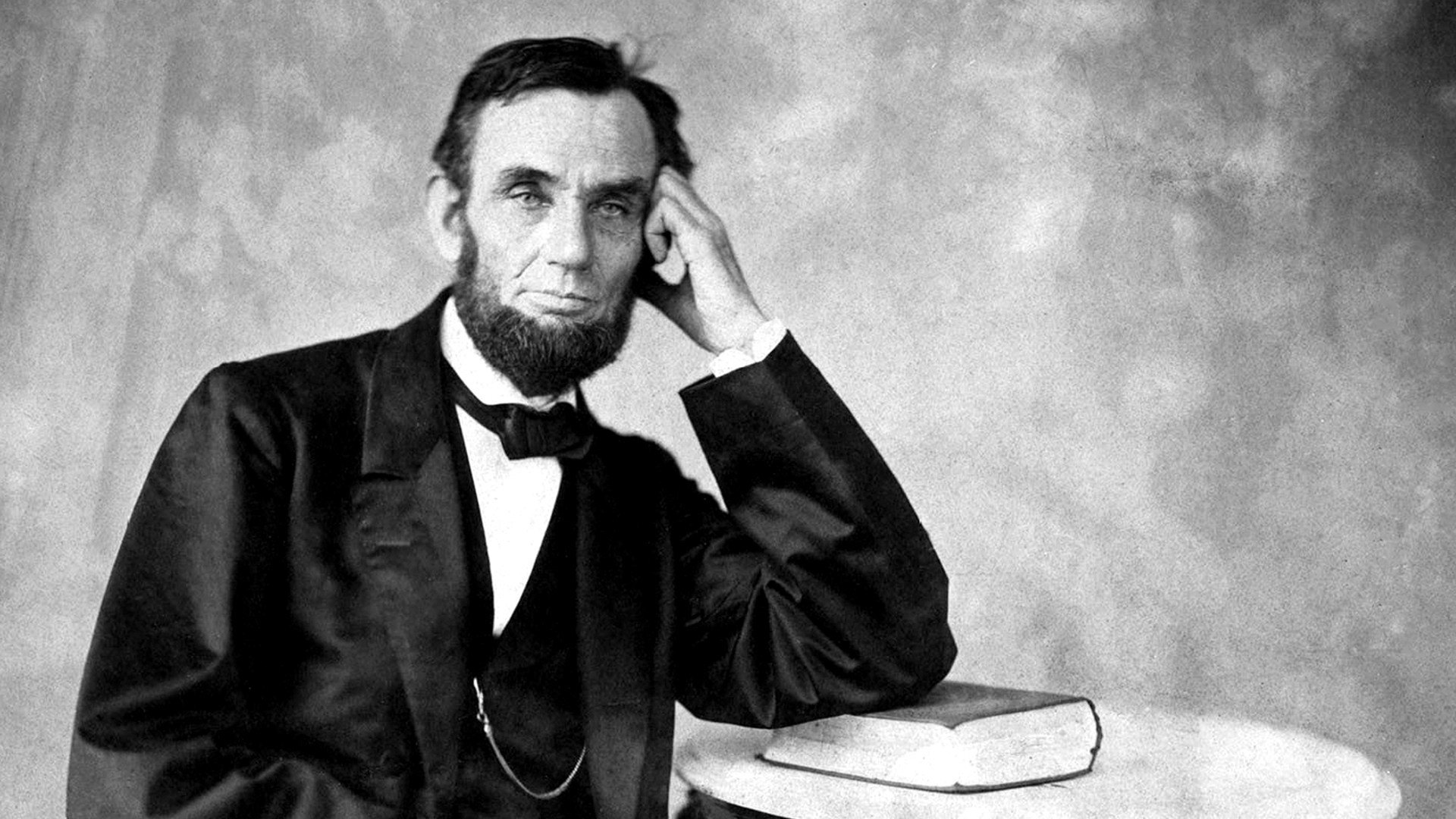

Was Abraham Lincoln a Christian? The book Abraham Lincoln, The Christian (1913) claims he was. Contemporary Lincoln biographer Allen Guelzo said in 2000, “He was not.” It’s a hard question: Lincoln was a skilled politician who understood his public, a compassionate president who agonized about sending soldiers to die, a private man with marriage problems that became public, and a thinker who thought long and hard about God.

Lincoln, born on February 12, 1809, grew up reading the King James Bible and contrasting its majestic language with the frontier Bible teaching that he treated in a variety of ways. First came parody. When Mr. and Mrs. Thomas Lincoln and daughter Sarah joined the Little Pigeon Baptist Church in 1823, teenaged Abraham did not. He often listened to sermons, though, and mimicked them afterward before a crowd of children until (as one child remembered) Lincoln’s father “would come and make him quit.”

Lincoln continued that practice into his 20s, once giving a memorable imitation of a preacher so plagued by a small blue lizard running up his leg that the preacher took off his pants and shirt while attempting to shoo away the reptile.

Then he moved from comedy to questioning the accuracy of the Bible and the divinity of Christ. Political competitors called him a deist who “belonged to no church.” Lincoln’s law partnership with William Herndon, a frontier evangelist for transcendentalism, did not help his reputation among Christians.

As Lincoln’s ambition grew, so did his caution in criticizing Christianity. Lincoln, as Whig nominee for Congress in 1846, ran against Peter Cartwright, the well-known traveling evangelist. In response to Cartwright’s charge that he was an infidel, Lincoln issued a statement published in The Illinois Gazette: “That I am not a member of any Christian Church, is true; but I have never denied the truth of the Scriptures; and I have never spoken with intentional disrespect of religion in general, or of any denomination of Christians in particular.”

Lincoln chose his words carefully. He did not say he affirmed scriptural truth, only that he never denied it. He did not state his respect, only that he had not been caught in disrespect. Neither statement was true about his earlier years, but Lincoln did display good manners during the 1840s. He concluded his public statement with a notice that he did not favor those with poorer etiquette: “I do not think I could, myself, be brought to support a man for office whom I knew to be an open enemy of, and scoffer at religion.”

Lincon in 1858 famously said, “A house divided against itself cannot stand.” He did not have to spell out to listeners the meaning of his reference to Matthew 12, where Jesus heals a demon-possessed man. The Pharisees said Jesus did it by using Satanic power, but Jesus responded that “every kingdom divided against itself is brought to desolation; and every city or house divided against itself shall not stand. … But if I cast out devils by the Spirit of God, then the kingdom of God is come unto you” (vv. 25–28, KJV).

Lincoln won Northern votes by implying that the South was evil and the North could somehow bring about the kingdom of God. He shied away from talking about war, but Congressman John Wentworth of Illinois went around proclaiming in 1860 that John Brown the previous year had been like John the Baptist, clearing the way for Lincoln, who “will break every yoke and let the oppressed go free.”

The “house divided” speech and fervent politicking afterward won him the Republican presidential nomination in 1860. To overcome the old accusations of deism, Lincoln included in his stump speech a line about how he could not succeed without “divine help.” Some Northern ministers ignored Lincoln’s previously expressed beliefs because the Republican Party was now the instrument to end slavery through a quick victory.

That did not happen, and for two years the strategies of Lincoln and his generals failed.

Beginning in 1862, Lincoln attended the New York Avenue Presbyterian Church in Washington on Sundays and sometimes Wednesday prayer meetings. Several long talks with pastor Phineas Gurley helped him go through “a process of crystallization,” which Gurley described as a conversion to Christ. Lincoln himself never said that, but he did tell journalist Noah Brooks, “I have been driven many times upon my knees by the overwhelming conviction that I have nowhere else to go. My own wisdom, and that of all about me, seemed insufficient for that day.”

That may have been for public consumption, but a key bit of evidence is a private note Lincoln wrote just after the Union’s second morale-sapping defeat at Bull Run. His “Meditation on the Divine Will,” a note found on his desk after his death, was not a politically pious missive for public consumption but an attempt to think through what was beyond human understanding.

“The will of God prevails,” Lincoln wrote. “In great contests each party claims to act in accordance with the will of God. Both may be, and one must be wrong, [for] God cannot be for and against the same thing at the same time.”

Who was right? Lincoln wrote, “In the present civil war it is quite possible that God’s purpose is something different from the purpose of either party…. I am almost ready to say this is probably true—that God wills the contest, and wills that it shall not end yet. By his mere quiet power, on the minds of the now contestants, He could have either saved or destroyed the Union without a human contest. Yet the contest began. And having begun He could give the final victory to either side any day. Yet the contest proceeds.”

Was it God’s will for slaves to be freed? When responding to clergymen from Chicago who asked him to carry out God’s will concerning American slavery, he said, “These are not … the days of miracles, and I suppose it will be granted that I am not to expect a direct revelation.” But Lincoln read the Emancipation Proclamation to his cabinet five days after Union forces stopped the Confederates at Antietam, stating (according to Secretary of the Navy Gideon Welles), “God has declared this question in favor of the slaves.”

In October 1862, he told four visiting Quakers that the war was “a fiery trial” and he was “a humble instrument in the hands of our Heavenly Father.” Lincoln said, “I have desired that all my works and acts may be according to His will, and that it might be so, I have sought his aid.”

In his “Proclamation Appointing a National Fast Day” in 1863, Lincoln called the war “a punishment inflicted upon us for our presumptuous sins to the needful end of our national reformation as a whole people.” Lincoln still spoke of sins of the whole people, rather than focusing on one particular sin, grievous as it was, in one particular part of the nation.

Lincoln’s proclamation emphasized how Americans had taken for granted God’s kindness: “We have forgotten the gracious Hand which preserved us in peace, and multiplied and enriched and strengthened us; and we have vainly imagined, in the deceitfulness of our hearts, that all these blessings were produced by some superior wisdom and virtue of our own.” That proclamation applied the Old Testament pattern—God’s faithfulness, man’s forgetfulness, God’s discipline—to a new people become “too self-sufficient to feel the necessity of redeeming and preserving grace, too proud to pray to the God that made us.”

Lincoln had not been above using religion for political purposes, but it seems that the war, along with the death of one of his sons, changed him. After previously questioning prayer, he was becoming a praying man. He told one general that as reports came in from Gettysburg during the first two days of fighting, “when everyone seemed panic-stricken,” he “got down on my knees before Almighty God and prayed. … Soon a sweet comfort crept into my soul that God Almighty had taken the whole business into His own hands.”

Pastor Gurley announced on one Sunday morning that “religious services would be suspended until further notice as the church was needed as a hospital.” Generals had already made plans. Lumber to be used as flooring on top of pews was stacked outside. But Lincoln stood up—he did that often and also said all prayers should be made standing up—and announced, “Dr. Gurley, this action was taken without my consent, and I hereby countermand the order. The churches are needed as never before for divine services.”

Lincoln needed the church and the Bible. By 1864, Lincoln was even recommending Scripture reading to Joshua Speed, his fellow skeptic from Springfield days. When Speed said he was surprised to see Lincoln reading a Bible, Lincoln told him, “Take all that you can of this book upon reason, and the balance on faith, and you will live and die a happier man.” When the Committee of Colored People in 1864 gave Lincoln a Bible, he responded, “But for this book we could not know right from wrong.”

He told pastor Byron Sutherland of the First Presbyterian Church in Washington that God “has destroyed nations from the map of history for their sins, [but my] hopes prevail generally above my fears for our Republic. The times are dark, the spirits of ruin are abroad in all their power, and the mercy of God alone can save us.” Lincoln increasingly saw no alternative to the spirits of ruin, as the war became one of attrition and the body counts surged.

Many cite Lincoln’s second inaugural address, with its call to “bind up the nation’s wounds,” as evidence of his emphasis on reconciliation, and that’s true. But the address also showed Lincoln’s sense that God was in charge: “Fondly do we hope—fervently do we pray—that this mighty scourge of war might speedily pass away. Yet … as was said three thousand years ago so still it must be said, ‘the judgments of the Lord, are true and righteous altogether.’”

I haven’t gone here into Lincoln’s marriage, which was a strange story unto itself that also drove him to prayer, but I’ll note one event because it pertains to the end of Lincoln’s earthly story.

On March 23, 1865, Mary Todd Lincoln, often intensely jealous, exploded at Julia Grant, the victorious general’s wife. When Lincoln intervened, “Mrs. Lincoln repeatedly attacked her husband in the presence of officers,” one of them said. He reported that Lincoln “bore it as Christ might have done, with an expression of pain and sadness that cut one to the heart, but with supreme calmness and dignity. … He pleaded with eyes and tones, till she turned on him like a tigress and then he walked away hiding that noble ugly face so that we might not catch the full expression of its misery.”

On April 14, when the Lincolns headed to the theater, General and Mrs. Grant did not go with them as originally planned, because Julia Grant refused to spend any more time with Mary Lincoln. Secretary of War Edwin Stanton and his wife had been invited as well, but Mrs. Stanton also refused to sit with Mrs. Lincoln. Finally, Stanton selected young major Henry Rathbone and his fiancée to go with the Lincolns.

Partway through the play, the member of the Metropolitan Police assigned to guard duty, bored and thirsty, wandered away from his post. John Wilkes Booth fired his fatal shot unimpeded.

Mrs. Lincoln was eventually declared legally insane. She did recall that at Ford’s Theatre, just before the shooting, she and the president had talked about a trip they hoped to take to Jerusalem.

This short account draws from two chapters on Lincoln in Marvin Olasky’s Moral Vision (Simon & Schuster, 2024).

Marvin Olasky is editor in chief of Christianity Today.