Elias Rodriguez has legally crossed the Texas-Mexico border hundreds of times. He knows every efficiency, like which crossings to use when or whether a snaking line of brake lights means you should stop for dinner in El Paso or hold out for tacos on the other side. He’s on a first-name basis with many Border Patrol officers, and he’s never had trouble crossing until last month. But now he’s being detained and questioned by American authorities each time, held for hours and subjected to intense questioning.

Rodriguez thinks he can explain this sudden scrutiny. At Thanksgiving, he escorted three Venezuelan children to be reunited with their mother in Venezuela after she was deported from America without them. His best guess is that the trip put him on some kind of Department of Homeland Security list.

A dual American and Mexican citizen, Rodriguez is also the pastor of a network of evangelical churches on both sides of the border. Each winter, he travels south with trailer loads of donated supplies for outreach events he helps host in and around Juárez, Mexico, that pair evangelism with a hot meal and gifts.

Since that Venezuela trip, the pastor has been detained for about two hours each time he’s come back to the US. He’s been asked about drug and arms trafficking—even threatened with arrest.

These encounters are “inconvenient and unnerving,” Rodriguez told me. “Sure, it makes me uncomfortable. But I told my wife if this is the cost that I have to pay for making sure those kids get to be with their mother [in Venezuela] again, it is worth it. I’d do it all over again.”

Over the last few months, as I researched the story of these left-behind children and the Rodriguez family’s efforts to help them, that willingness to live with discomfort became a constant theme—and a source of personal conviction.

Would I do what Elias Rodriguez and his wife, Sandy, have done? I’ve asked myself more than once. They dropped everything to drive across Texas and pick up three kids they had never met, taking (unofficial) custody of them indefinitely while working out an improbable plan to get them back to a country with dangers well beyond most Americans’ comfort zones—and with no direct flights to or from our shores.

And now that those three children are reunited with their mother, the Rodriguezes have taken in two more children in a similar situation. Another American family nearby is also voluntarily (and unofficially) fostering strangers’ children: 1½- and 5-year-old girls whose parents were deported without them.

Both American families are my friends, and when I see them putting Matthew 25 into practice, I’m confronted with my own uncomfortable hesitations. To go and do likewise would make my family uncomfortable. A common retort from immigration restrictionists asks whether immigration supporters would be willing to take new arrivals into their homes. If I’m honest, if they’re toddlers, I’m not sure.

After all, I already have a lot of responsibilities on my plate: family, church work, and an endless calendar of appointments to which I must drive my kids. The thought of suddenly and indefinitely adding more children to the mix—children who miss their parents, who may be markedly younger than my own, who may not speak English—well, suffice to say it’s a daunting prospect. Undeniably uncomfortable.

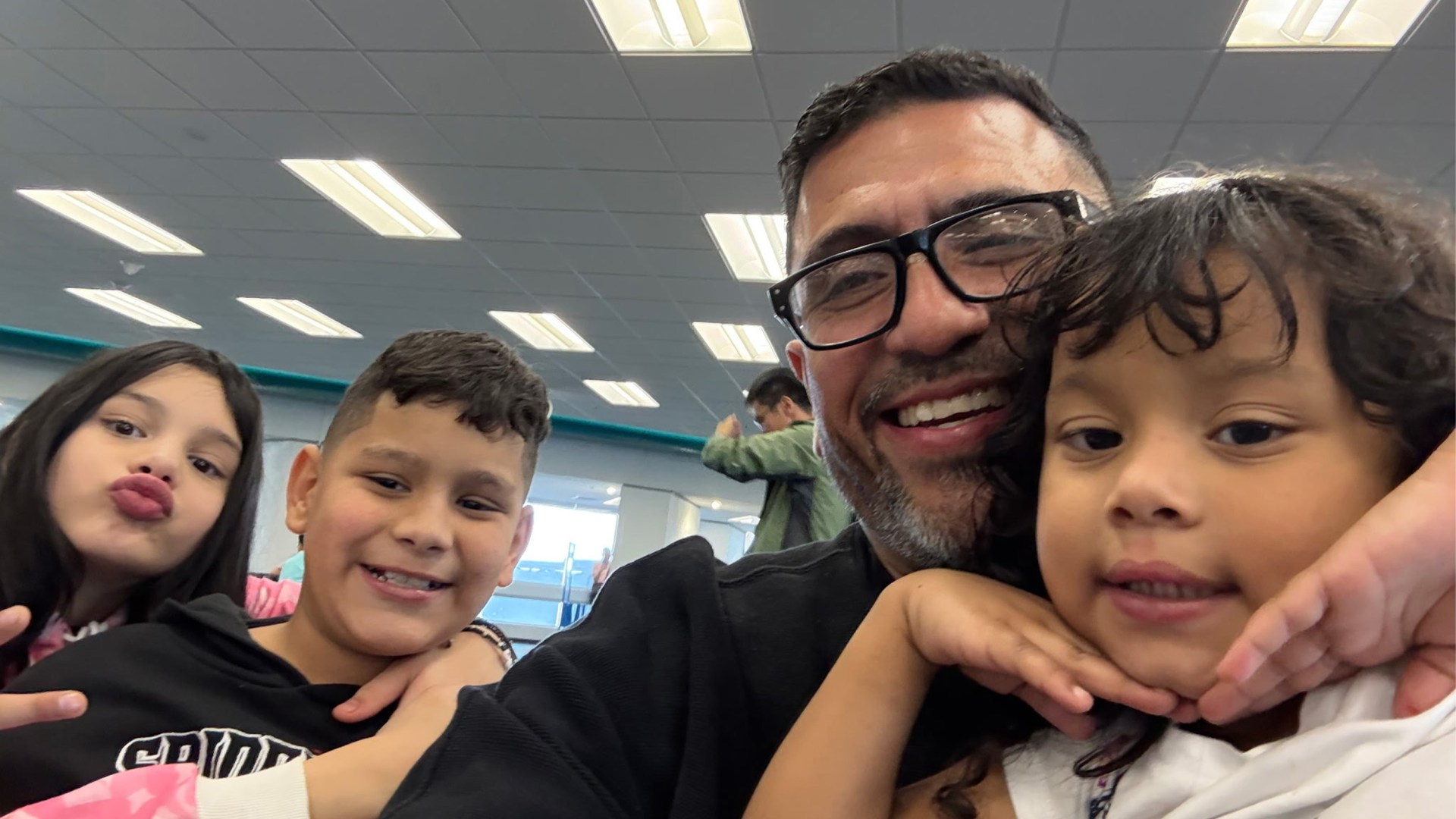

Image courtesy of Elias Rodriguez.

Image courtesy of Elias Rodriguez.Rodriguez doesn’t fit into neat political boxes, and that’s not comfortable for most of us either. He supports strong border policy and yet shelters migrants. He believes people who break the law should be deported—including the mother whose children he returned to Venezuela—and yet he took her children into his own home. Amid a storm of extremism, this conservative pastor is a lighthouse of both mercy and justice. He has eschewed our culture’s dangerous alchemy of high-minded public judgment and street-level disengagement in favor of true service in the model of Christ.

This commitment to integrity over personal comfort is what must distinguish the church, Rodriguez told me. “Obedience to the Lord will always carry a cost,” he said. “It is will always have a price tag, and sometimes the price tag is that you don’t get to have an easy life. It is not going to be comfortable.”

I don’t think it’s just my Texas twang talking when I say that I don’t think there’s much difference between the way all and our sound, though I guess you can test my theory. Try saying these phrases out loud and decide for yourself: God of all comfort. God of our comfort.

And whether they sound similar or not, the American church has blurred their meanings. Too often, what the Bible says and what we hear are two different things—and the difference matters enormously.

In 2 Corinthians 1:3–5 (ESV), Paul writes to the church in Corinth, a city then known for worldly power and prosperity, decadent living and luxurious comforts. This was a church, that is, with which we middle class Americans have a lot in common. Here’s how he opened the letter:

Blessed be the God and Father of our Lord Jesus Christ, the Father of mercies and God of all comfort, who comforts us in all our affliction, so that we may be able to comfort those who are in any affliction, with the comfort with which we ourselves are comforted by God. For as we share abundantly in Christ’s sufferings, so through Christ we share abundantly in comfort too.

I’m sure all and our don’t sound so similar in the original Greek. But I wonder if those early Christians struggled as much as I do with conflating the two. Because here’s the uncomfortable thing about that verse: It’s really not about our comfort at all.

For all the talk of Christian nationalism and the conservative-versus-liberal battles that dominate this age, Rodriguez believes the fundamental problem with today’s American church is that most of us have grown enchanted by a false god of our own comfort. We have accepted sloppy seconds—a nice life, nice stuff, nice neighborhoods, and nice friends—in exchange for any uncomfortable situations that put us squarely in need of God’s comfort, with which he promises to bless us when our lives are dangerous or unpredictable. As safe and predictable as these lives we’ve built for ourselves seem, when we functionally worship the tawdry pursuit-of-our-own-happiness idols we’ve constructed, can we see how dangerously close we are to gaining the whole world yet losing our very souls (Matt. 16:26)?

This is not the way of Jesus, who promises us abundant life—life abundantly full of more than our own comfort.

As a winter storm descended over much of the United States last week, millions of us stayed at home—iced in and increasingly focused on ICE (Immigration and Customs Enforcement). As tensions escalate, I worry that simplistic partisan opinions about federal immigration enforcement have a way of dangerously freezing us in place.

Here’s what I mean: Armed with nothing more than the knowledge of how someone voted in 2024, most of us could place a winning bet on where that person lands on any number of complicated political and social issues. And though most of us fancy ourselves free thinkers, the truth is, few of us are. We tend to take up the party line, even to the point of refusing to listen to people on the other side. This makes us feel like we belong. And it can feel so principled, but in practice, we’re picking at the threads of our fraying social fabric.

For us as Christians, this is a moment that demands more than attention or anger or sympathy. It demands that we turn toward peacemaking. It demands we imitate Jesus in tangible care for the people right in front of us, including those—like the tax collector who hosted him for dinner (Luke 5:29–32) and the unclean woman who washed his feet (7:36–50)—who make us uncomfortable. Jesus did not speak in platitudes or diatribes. He did not deal in vague generalities or broad stereotypes. He drew near to broken people, even at the cost of his own reputation (Mark 3:21).

One reason we need to follow Jesus even to uncomfortable places is what happens to us when we finally draw near in the same way. The things we once assumed were simple become far more complex. And that’s a good thing! In this fractious age, growing in understanding is how we become repairers of the breach and restorers of the paths between us (Isa. 58:12). I’ve seen it play out in my own community these last few weeks as a whole band of Christian women in my town has joined a group text to coordinate practical aid for these children in our friends’ care.

The women in the text chain are mostly politically conservative and supportive of strong immigration policies. Most probably voted for Donald Trump. Many of us in the group, at some time or another, have probably nodded along to talking heads on cable TV offering proposals of simplistic solutions for complex problems. But the group text demands deeds, not words. We are coordinating meals and securing car seats and dropping off clothes and toys. Some women have helped buy airplane tickets. Some have offered to babysit, while others have held little hands while crossing busy streets.

All this is simple too, but it has brought us each to see the faceless, nameless “immigration issue” with a lot more complexity. It has taught us to see both good and bad, broken systems and broken laws, mothers and children, justice and mercy.

These tensions are uncomfortable by human standards—they can make us feel like outsiders in our preferred tribes and transform us into people who are more difficult to politically manage and control, which feels risky. And yet as we step into these uncomfortable places, God “draws near to us in our fear and uncertainty and pain and suffering,” as Rodriguez said to me. In the messiness of it all, we’re met by the God of all comfort—not merely our own.

Carrie McKean is a West Texas–based writer whose work has appeared in The New York Times, The Atlantic, and Texas Monthly magazine. Find her at carriemckean.com.