I am a product of second-wave feminism of the 1960s. By the time I was a child in the ’80s, movies were full of women in shoulder-padded jackets leading employees from their corporate desks. The working mom was alive and well, figuring out how to balance her professional and family responsibilities. My grandpa was picking me up after school and watching me until Mom got home from work.

I am a product of second-wave feminism of the 1960s. By the time I was a child in the ’80s, movies were full of women in shoulder-padded jackets leading employees from their corporate desks. The working mom was alive and well, figuring out how to balance her professional and family responsibilities. My grandpa was picking me up after school and watching me until Mom got home from work.

So I came into my stay-at-home mom role slowly, with frequent handwringing and doubts. I was in full-time ministry before that, in a form of work that demanded loads of energy, crazy hours, and a great community of support. I had dreams for the way my career and calling would flow into my children’s lives. I wanted a home where high-school kids I ministered to could stomp in and out and eat all our tortilla chips. I wanted my boys to experience the socialization that comes from being around caring young people (my volunteer leaders). I wanted my children to know the part of me that leads 500 kids in the “Jai Ho” dance on stage, or sits with a 16-year-old girl over a cup of coffee, hearing about her family and her relationships, and letting her know she is valued.

When my husband’s job moved us across the country, the community I depended on for childcare was gone, and my job was not transferable. Instead of high-school field hockey practice and prayer meetings, my days in San Francisco became centered on the playground and story time at the library.

I’m grateful for the feminist movement, yet also uncomfortable in it. Some Christian women use the term egalitarian to describe their beliefs about women and the church, assuming it’s less loaded, less political than the “f-word.” But I struggle in that as well, knowing that even Christian working women have more opportunities thanks to the work of pioneering feminists. I constantly question my choice to be home. I struggle with this choice I’ve made to become the grocery shopper at 10 a.m. in my yoga pants, two kids piled in my shopping cart. After our cross-country move, when asked what I do, I found myself saying: “I’m just a stay-at-home mom.” Why has it been so hard to value my work at home?In The Feminist Mystique, Betty Friedan explained part of what has led to my stay-at-home discomfort:

The only kind of work which permits an able woman to realize her abilities fully, to achieve identity in society in a life plan that can encompass marriage and motherhood, is … the lifelong commitment to an art or science, to politics or profession.

Friedan and other second-wave feminists saw domesticity as holding women back from something much greater. By and large, the goal of feminism was to liberate. Women broken by our society’s narrow expectations were released from what for many was a jail cell of forced domestic life. When a prisoner is freed from her small, dark room, she blinks at the new, wide-open landscape. That message of liberation resonated with many women. Yet what of those women who had happily chosen their life at home, who had not been oppressed, who had found their calling within the family?

By the time my generation appeared, our society had bought into such a view of women and their value. Some women had pursued something meaningful, committing to “art or science, to politics or profession,” while the rest of us had walked back into a prison. Essentially, that judgment nullified the contributions of women for centuries. None of us would say women were insignificant throughout the story of humanity: their work of making babies, breastfeeding, clothing their families, planting gardens, gathering food, feeding and passing on stories, songs, and the arts, and providing emotional support for the community—all possible or necessary tasks of today’s stay-at-home mom, and all tasks associated with the domestic realm—have allowed for our existence.

If we really believe a woman is wasting her mind, time, and talents by staying at home now, then it’s always been a waste.

I have been given a bright, open job to spend my days playing dragons and cars with my boys. When I fail to value the narrow yet deep work of raising children, to value the work of building a safe place, I miss out on the joy of recognizing myself as a working woman.

I’ve spent the past couple of years looking for nods of approval of my choice. I won’t always get them. The question is not whether we receive the approval of others, but how we begin to value all women’s work, whether in the home or in the office.

It’s only by embracing the deep value of a life raising my boys that I can look beyond my home into a world aching with need. It’s only when we are free enough to understand liberation that we can spread out under its banner.

Micha Boyett blogs at MamaMonk.com, and just moved from San Francisco to Austin with her husband and two boys. She’s written for Her.meneutics about Ann Voskamp’s One Thousand Gifts.

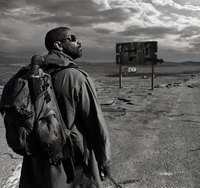

With one post-apocalyptic thriller on the big screen, another is in the works.

The Book of Eli, set in America after the apocalypse, stars Denzel Washington as a man with a mysterious book that might hold the key to man’s salvation. USA Today brings us a firstlook at the film, with five images.

Co-director Allen Hughes told the newspaper, “This is the first time I can remember where it feels like America is, at its core, vulnerable. We’re mortal. After 9/11, the reaction showed how thin that line is between order and chaos. It feels like we’re at a boiling point. That’s why these themes of redemption and salvation are so powerful now.”

Our daughter Penny started kindergarten six weeks ago. At the end of her first day of school, she greeted me with, “Mom! I didn’t miss you!” She’s loved every moment since. I’m sure much of her experience is typical—she walks to school, she works on spelling and reading and basic math concepts, she plays on the playground at recess. And yet Penny’s experience also highlights significant changes in American education over the past few decades because Penny has Down syndrome and an Individualized Education Plan (IEP) and regular therapy sessions. Hers is an “integrated” classroom, with two teachers and a classroom aid. Forty years ago, she might not have been eligible to attend public school at all, much less in a classroom alongside her typically-developing peers.

Our daughter Penny started kindergarten six weeks ago. At the end of her first day of school, she greeted me with, “Mom! I didn’t miss you!” She’s loved every moment since. I’m sure much of her experience is typical—she walks to school, she works on spelling and reading and basic math concepts, she plays on the playground at recess. And yet Penny’s experience also highlights significant changes in American education over the past few decades because Penny has Down syndrome and an Individualized Education Plan (IEP) and regular therapy sessions. Hers is an “integrated” classroom, with two teachers and a classroom aid. Forty years ago, she might not have been eligible to attend public school at all, much less in a classroom alongside her typically-developing peers.

Penny’s academic skills are similar to those of her friends at the moment, but her behavior is different. Her teacher breaks the day down into 10-minute intervals, with a sticker for every stretch of self-control Penny displays, and frequent rewards—”Freeze Dance,” a prize from the prize box, the chance to read out loud to the class—throughout the day. It’s a lot of work to have Penny in the classroom. And it’s a great place for Penny. I hope and pray that it’s also a great place for the other kids, that Penny’s presence contributes to the learning environment in such a way that she is a blessing to her peers, even as she is blessed by their inclusion of her.

The New York Times recently ran a series of opinion pieces about “differentiated learning,” in which teachers modify curriculum so that children of various academic abilities can all work in the same classroom at the same time. Most of the commentators held up differentiated learning as an ideal, but they also expressed concern about how this learning works in practice. Cassandra Davis attributes higher test scores for struggling students to inclusion and differentiated instruction, but Michael Petrilli counters that differentiated learning harms high achievers because teachers pay less attention to the kids who least need their help. Frederick Hess summarizes the disparity: “low-achieving students benefit when placed in mixed-ability classrooms (faring about five percentage points better than those placed in lower-track classes) but high-achievers fared six percentage points worse in such general classes.”

My own experience in school couldn’t have been more different than Penny’s. I skipped kindergarten because I came home crying a few weeks into the year. “When is it going to get harder?” I asked my mother. I went on to excel in school, but I cried again in fourth grade when I received a B on my report card for math class. I remember forgoing social events and working all the time in high school. It wasn’t until I was two years into college that it dawned on me that school was about more than my personal academic achievement. As I learned more about Jesus’ priorities, I began to see my single-minded devotion to getting good grades as a problem instead of a sign of success. I had learned a lot about literature and calculus and historical events. I could speak Spanish. I would soon graduate from a good college with good grades. Yet I hadn’t learned much about serving other people or about understanding the gifts I could receive from others, even, especially, people who weren’t as academically inclined as me.

In Mark 9, and elsewhere within the Gospels, Jesus’ disciples remind me of myself. They bicker with each other over who is the greatest, over which one of them will gain the most power and prestige in God’s eyes. They are climbing the equivalent of today’s corporate ladder, a ladder that now begins in the classroom, with the rungs of academic achievement leading to productive employment leading to success in the eyes of their peers. And then Jesus disrupts their posturing with a child: “He took a little child whom he placed among them. Taking the child in his arms, he said to them, ‘Whoever welcomes one of these little children in my name welcomes me; and whoever welcomes me does not welcome me but the one who sent me.’”

I suppose I could say God disrupted my own posturing with a child too. Having a child with learning disabilities has challenged my notions of the purpose of education and offered me a broader vision of God’s kingdom. The potential exists for a similar positive disruption to occur throughout the nation’s classrooms as teachers attempt to educate students with diverse needs. Having a child with a disability has opened my eyes to the ways in which my education—filled with enrichment programs, dedicated teachers, and independent studies—was nevertheless an impoverished one. I never learned alongside or from people who don’t share my academic inclinations. It took me a long time to recognize that my own academic strengths correspond to weaknesses in my character and to recognize that each of my fellow beings has the ability to teach me, if only I have the eyes to see them as God’s beloved.

The purpose of education, at least from a Christian perspective, is not simply academic achievement or increased GDP. Education is one aspect of spiritual formation, in which we learn how to love and serve one another as Christ has loved us. Classrooms with differentiated learning serve “the least of these,” even if they lead to less academic success for peers with higher IQ’s. But I would argue that differentiated classrooms serve the high-achievers too. In some ways, classrooms with differentiated learning mirror the kingdom of God, a kingdom in which merit does not gain us a seat at the king’s table but rather the invitation of the king to understand ourselves as dependent and vulnerable human beings who are both gifted and loved.

The description and images remind me of The Road, the film adaptation of the Cormac McCarthy book of the same title which was supposed to release late last year before being shelved indefinitely. USA Today also gave us a first look at that film last summer. IMDb says The Road is now slated for an Oct. 16, 2009 release, but the official website still says “Coming Soon.”