When I was in second grade, our elementary school held a play that told the tale of an infection—played by a third grader in a dragon costume—invading the body and then being vanquished. My class was cast as macrophages, which chew up invaders to the body. We were told that they are “big eaters,” but it was not until many years later that I learned that macrophage comes from the Greek word for “big eater.” It is an apt description.

I don’t know if this was the inspiration for it, but I became a macrophage biologist, and these cells proved to be a source of endless wonder to me. It is an amazing thing to peer into a microscope or perform an experiment and gain a glimpse into this vast invisible world within our bodies. In the great story of God’s work in the world, the drama of macrophage-versus-invader is a small but important tale.

Munching Sentries

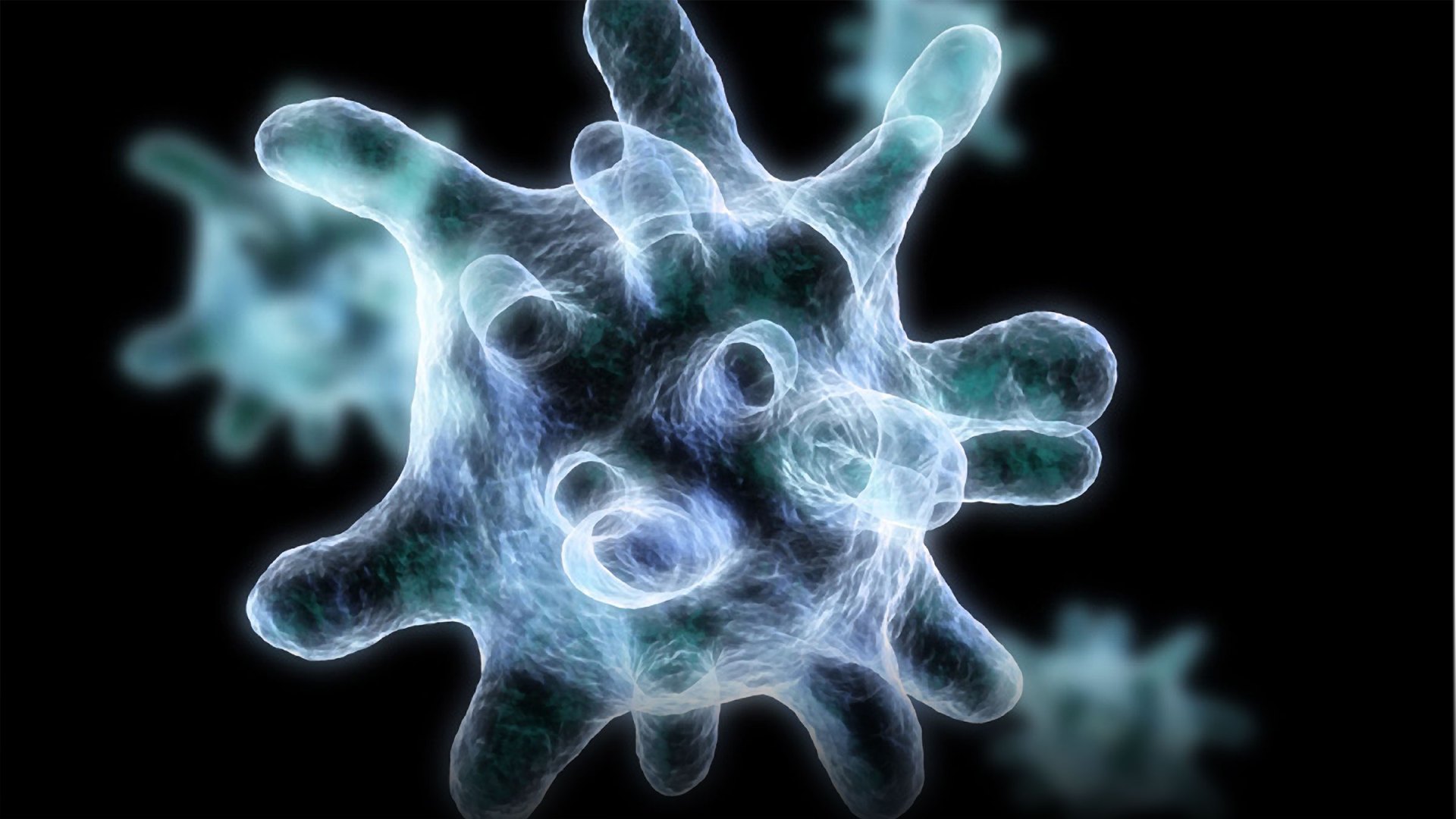

So what are macrophages? They are a type of white blood cell, which are all involved in protecting the body from invaders and from rogue cells. Macrophages are clear, with long arms that help them move extending from their bodies. Found throughout the body, standing guard in different organs as sentries, macrophages patrol for irregular activity and munch on anything they deem suspicious. These hungry defenders also help clean up wounds, removing dead cells and debris so new, healthy tissue can grow.

Dying cells are easy for a macrophage to recognize: they put up a cellular white flag, which is seen by the macrophage as an invitation not to negotiate terms of surrender but to have some lunch. However, if a group of disease-causing bacteria were hiding in the body, there would be no “eat me” sign. Instead, the macrophage has a variety of receptors that recognize certain parts of the invading bacteria. If the appropriate part of the offender touches this receptor, a wire is tripped. An alarm system inside the cell sets off the eating process macrophages are known for, which is called phagocytosis. The cell wraps itself around the bacterium and engulfs it, isolating it into a small bubble called a phagosome.

The macrophage now has a live prisoner. Because they lack teeth, macrophages must use chemicals to digest their mouthfuls. These chemicals are contained in compartments called lysosomes, which are filled with the harshest substances found in the body and are strongly acidic. The signal that compels the macrophage to engulf the bacterium also causes the cell to start concocting a new batch of this digestive brew in order to break down the captured cell. The lysosome fuses with the phagosome and quickly digests the bacterium, breaking it into small pieces of debris. After digestion, the chemicals are then neutralized in order to protect the macrophage from being damaged.

Some digested particles are put to good use: They are displayed as trophies on immune molecules studding the outside of the macrophage, which are checked routinely by other white blood cells for evidence of infection. This hands off the immune response of the generalist macrophage, which will kill anything suspicious, to specialized immune cells that mount targeted attacks against the specific invader. The resulting well-coordinated campaign deals the knockout blow and clears the body of the infection. Without the intelligence provided by the macrophage, these specific-acting cells would be unaware of the infection. This handoff allows the macrophage’s lunch to give important information to the rest of the body and help it to clear out harmful invaders.

Our little play ended as this story does, with a body cleared of infection and able to continue thriving, thanks to a little help from the macrophages within it. There are many mysteries left to explore about their function and their role in the body. I am grateful for the opportunity that we have to peer into the mysteries of God’s creation and to praise him for the cellular wonders enjoying lunch within us.

Joanna Daigle is a graduate student studying biochemistry at the University of Saskatchewan.