Farming has been in my blood for seven generations. For seven generations I have been rooted to land and place.

Trace our worn family line back as far as you can, and you find we are a people of place-makers who work the earth, grounded in a place by the roots of our plants. We’re as common as dirt. It’s our ground that grounds us.

Walter Brueggemann and others have noted that adam—the Hebrew word for man—shares its root with adamah, the word for ground. We’re not just from the earth. We’re of it. Place isn’t just where we live—it’s part of who we are.

This spring, I sat in a home in Romania that belongs to a young Russian man, Damir, and his wife, Larianna, who’s the daughter of a Ukrainian and a West African. Their children’s paintings dance across the walls, welcoming us. Larianna has just pulled a loaf of apple bread out of the oven. She sets it on a trivet on the corner of her table, beside a stack of plates.

“My father was from Guinea,” she says. “He came to Ukraine to study at university, way back when Ukraine was still part of the Soviet Union, and he fell in love with my mother; she’s Ukrainian.” Larianna cuts generous slices of the steaming bread and plates them before us. “My father’s black and my mother’s white. But because it was the Soviet Union then, it was not allowed for her to get married to an African.”

I listen—seated beside a Russian man in Romania and eating his Ukrainian wife’s apple bread—and taste the words that Jesus spoke: “I was a stranger and you welcomed me” (Matt. 25:35, throughout).

“As we were fleeing Ukraine,” Damir says before pausing to take another bite, “a Romanian border guard saw my Russian passport and asked a lot of questions: ‘Where are you going?’ ”

I wonder: Where do you go when the very dust from which you’ve come quakes beneath incoming tanks and exploding bombs? When the roof meant to shelter your children becomes a target on some war-monster’s radar screen?

“No one leaves home unless / home is the mouth of a shark,” wrote Somali British poet Warsan Shire. Where do you go when the soil on which you were birthed won’t give you the right paperwork and the fury of hades breaks loose?

I know where we as farmers go in spring, generation upon generation. We go out to the fields. We till the earth. And we plant seeds that break open deep down in the earth, seeds to unfurl and grow roots and reach for the sun.

For Brueggemann, the land was a potent symbol of life and fertility for the ancient people of Israel. What happens to a plant that’s pulled out by its roots?

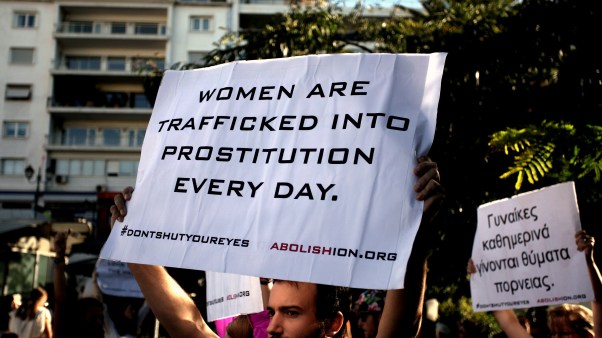

Photo by Esther Havens

Photo by Esther HavensIt’s mid-morning, also in early spring, just before the wheat grows green in our fields, when I meet Viktor, his wife, Iryna, and their teenage son—a Ukrainian family—who gave up their place in Moldova to help those fleeing their homeland in the days

right after the Russian invasion.

“We were missionaries, serving in Moldova,” Viktor says. “But because my wife speaks both Ukrainian and Romanian, when the war started we went to the Ukrainian-Romanian border to help with coordinating, to help Ukrainians meet with Romanians to find safe places. We didn’t expect to actually leave Moldova, or to end up in Romania, but God opened the door for us. We gave up our place in Moldova. There was a need.”

I look across the table into his wife’s eyes. She had a safe place of her own—far from sirens, falling bombs, the trauma of war. Why give that up just to help others searching for a safe place to breathe and exist on this planet?

“At first, we stayed with about 20 other Ukrainians in a Romanian horse barn. They didn’t know how to speak Romanian or what to do or where to go for help. We help them find their way …” Viktor’s voice trails off.

“Eventually we had to manage the bills. Electricity, utilities, rent, everything … though we had our own place back in Moldova.” Iryna speaks slowly, emotion welling. “It is very hard. Every month, we have almost nothing left.

“We could go back. But we believe God puts us in a place. And we see that … there is a need for us to be here. Yeah, it’s not easy. But …” She brushes back tears.

I nod, feeling the ache and sacrifice of her words, the testament and witness of their lives. They are dying to self because others are dying to live.

“The will of God—that is the place for us,” Victor says softly. “His will is where we live.”

What if the will of God is a place we choose to inhabit too? “God, people, and place cannot be separated,” John Inge wrote in A Christian Theology of Place. The places we live aren’t merely geographical but are relational too. What if we eschewed comfort to be the comfort of Christ? I’ve seen this too as one farmer in a long line of farmers: “Unless a grain of wheat falls into the earth and dies, it remains alone; but if it dies, it bears much fruit” (John 12:24).

In the summer of 2017, I walked down roads in Iraq, the land of the Tigris and Euphrates rivers, where the world’s first known farmers grew the earliest strains of wheat. Every year, as they have for hundreds of years, these floodplains deposited nutrient-rich, alluvial soil, creating some of the most fertile dirt in the ancient world.

I walked with Joseph, a 23-year-old Iraqi man, through the rubble left by ISIS where his hometown once stood. On the morning of his 22nd birthday, he woke to his mother singing as she prepared a feast for his birthday dinner. Before she set the plates out, ISIS invaded. I stopped in the middle of the war-wrecked street and quietly asked Joseph, a young man who’d once gone to church every Sunday, how he feels about God.

Joseph’s eyes didn’t leave mine. “I don’t … feel anything about God. I don’t … believe. I used to, before all of this.” He waved his hand like he could brush away the misery that surrounded him. “But now I think, There is no God. There is no God who cares about us.”

Then Joseph leaned in, inches from my face, and asked me a question that cut me right to the quick. “Am I wrong?”

I could feel his pain burning in my chest. When love is mostly self-seeking, do people mostly miss seeing the face of God?

Is God only more clearly seen in the world when we seek out and speak out and sacrifice for the interests of others in the world? Is this what it looks like to place myself in the generations of God’s will?

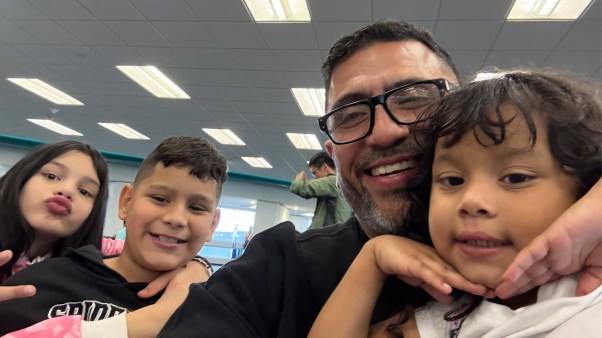

Photo by Esther Havens

Photo by Esther Havens“Somebody always wants more” is what Kamila, a young Ukrainian woman who fled with her family to Romania last spring, tells me before we walk across a city square, a flock of pigeons taking flight. “More power, more money, more control, more, more, more. But most people, they just want a normal life. Peaceful. But we end up going through all the difficulties, experience all the horrible things—because someone wants more.”

I see in Kamila’s young eyes what I saw in Joseph’s that day in Iraq.

But Joseph had stepped closer and I’d felt his wild, hurting breath on my face as he spoke. “The world doesn’t consider me even human,” he said. “You can get on a plane and fly back to your nice little island of safe. But me—I’m left in this place to exist as nonhuman—and there’s no one, no United Nations, no united people, no united front—no one who cares how I exist, where I exist, or even if I exist.”

Is the church still a place of fertile soil? A place where every believer becomes a seed—rooted in Christ, dying to self, and producing a harvest that sustains the fleeing travelers who crave the smallest place

of peace?

My father, my father’s father, and his father before him all taught the next generation an important truth: Farmers can have faith that the soil under our feet is fertile with abundance, even enough to share.

“I’m Russian,” Damir says with his Russian passport in one hand and sweet apple bread in the other. “But I’m not only a Russian citizen; I’m also a Ukrainian refugee. I have Ukrainian kids. I have a Ukrainian wife. And I’m living here in Romania, serving in ministry, helping Ukrainian refugees grow closer to God.” He tastes the last of his bread.

“And honestly,” Damir speaks softly, leaning in, “my citizenship is not Russian, not Ukrainian, not Romanian. My citizenship is heaven.

I have heaven.”

I finish the last of my apple bread too. And taste conviction. What does it profit a person to hold citizenship in the best of lands yet care little about the plight of image bearers of God in other lands—and so end up profaning your own citizenship in heaven?

Doesn’t the way we respond to those in need of a safe place reveal what kind of place our souls truly are? Do we desecrate a place when we dehumanize a person?

Photo by Esther Havens

Photo by Esther HavensThis is the reality before each of us: The passport every single person carries is the image of God, which means every person comes from a place that warrants dignity. Then immigration is more than a mere political debate—it’s ultimately about a person’s dignity.

Jesus, too, migrated—from heaven’s heights to the human race.

Jesus, too, fled with family, from an unsafe place to Egypt.

Jesus, too, knew what it was to be uprooted and suffer injustice.

And it’s Jesus, too—the refugee—who is seen in the face of every refugee.

Larianna reaches across the table, offering another slice of her warm apple bread.

“Everybody wants to have a stable life. A lovely pillow, a lovely everything. But for your soul to grow? Your faith to grow? You sometimes need to lose something.” Larianna leans forward and repeats herself, to make sure I understand: “To grow your belief, you may need to lose something.

Live all of your life in one house and never lose anything? It’s hard to grow your faith. Because you always have your stable life.”

Her voice is soft, but something hard in me is breaking open.

“But if you lose things … if you lose everything … your faith grows and God becomes everything.” Larianna nods, her eyes holding mine. “It doesn’t matter if you’re with food, without food, with roof, without roof. What matters is that you have heaven, that you have God. This is the only way to happiness.”

Have I forgotten that, in the upside-down kingdom of God, you have to experience loss to grow?

This year, like the last, the wheat grew tall across our farm—this place of dirt and sky and sheep and seed that I call home. Each ripe head bowed humbly down. After the harvest, I walked the dirt fields, knelt down, and gathered into my open palm a seed or two that had fallen to the earth.

To be human is to come from humus, from the earth, from the land. And to belong to Christ is to be all at once a sojourner, a safe place, and a surrendered seed in a strange soil that breaks open and lets go. To grow and harvest abundantly more.

This is what my father told me. It’s what we tell our children, the next generation of farmers in this place, on this land: When you plant a kernel of wheat in the ground, its first growth is always downward, not upward, the seed sending out an embryonic root, called a radicle, pressing lower into the soil.

Growth always begins in this radical downward mobility—this place of letting go, going lower into the wide expanse of the upside-down kingdom of God.

Ann Voskamp is a New York Times best-selling author and farmer based in Canada. Her most recent book is Loved to Life.

Esther Havens is a humanitarian photographer and storyteller based in Dallas.