During my time as a college history professor, I taught a required course on Western civilization. Like many faculty peers, I tried different ways to motivate business and premed majors to take it seriously.

One common method was beginning the semester with C. S. Lewis’s classic essay “Learning in War-Time.” This essay (also the subject of Mark Meynell’s January/February article “War Changes Everything—And Nothing”) eloquently advocates maintaining a commitment to the life of the mind amid adverse circumstances. Professors often stretch the “wartime” metaphor to fit any stressful situation—a global pandemic, political turmoil, or a losing football season.

But what is learning like when the war isn’t metaphorical? In Serving God Under Siege: How War Transformed a Ukrainian Community, Valentyn Syniy details his experiences in leading a Christian academic institution in literal wartime conditions.

My own current work conditions, as the director of a Christian learning community on a public university campus, are admittedly far less challenging. But Syniy’s account offers worthy insights for anyone engaged in the work of higher education.

Syniy is the president of Tavriski Christian Institute (TCI), an evangelical seminary in the southern Ukrainian city of Kherson, near the Crimean Peninsula. In 1996, several pastors there desired to create a regional Bible college for ministers. They reached out to Glen Elliott, a missionary from the United States. Several Christian colleges in the US became involved, resulting in the creation of TCI. The school purchased land along the Dnieper River and began constructing buildings in 2003. Two years later, Syniy signed on as rector.

Yet Russia’s 2022 invasion upended life for TCI’s students, teachers, and staff. As the Russian army attacked and occupied Kherson, Syniy and his family fled the city, along with many TCI students and staff. They traveled over 500 miles to a safer location in the western Ukrainian city of Ivano-Frankivsk.

Interestingly, however, TCI’s history plays only a minor role in the narrative. In fact, readers learn about the school’s founding only toward the end.

Instead, Syniy focuses on how the TCI community pursued other forms of Christian service. They coordinated the evacuation of refugees from Kherson and Kyiv, Ukraine’s capital. They started a coffee shop ministry to local youth patterned after a similar effort in Kherson. Syniy raised humanitarian funds from Dutch and US sources for communities impacted by the war.

Meanwhile, Syniy and his students worked to maintain some semblance of normal life. In the book, he describes celebrating his daughter’s wedding, speaking at a pastor’s retreat, and going on long walks with his dog Sherri.

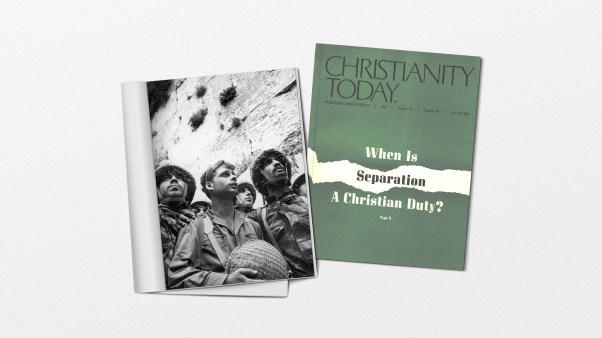

Yet certain aspects of prewar life did not survive the Russian invasion. One casualty, it seems, was any sense of unity between Russian and Ukrainian Christians.

TCI had received its accreditation from the Euro-Asia Accrediting Association (EAAA), which included many Russian and former Soviet institutions. In March 2022, Ukrainian seminaries held a conference called The Russia-Ukraine War: Evangelical Voices, an appeal to help resist Russian aggression. Presenters, including Syniy, decried notions of “Russian Order” used to justify the war, and they called on Russian Christians to join them in condemning it.

Three months later, the EAAA organized a Zoom conference that included seminary leaders from Asia, Moldova, Ukraine, and Russia. Syniy attended while sitting at a military checkpoint on his way back to Kherson to evacuate refugees. In the book, he recalls his rising anger as a Russian seminarian pleaded for Christian unity and expressed skepticism about reports of Ukrainian suffering:

Here he was, sitting in a warm, cozy study with books behind him, drinking coffee from his porcelain cup, while hundreds of people around me had no clean drinking water.

The inability of Russian Christians to condemn their country’s actions led Ukrainian seminaries to withdraw from the organization. “We found ourselves in two different worlds,” Syniy writes. “We had no choice but to separate.”

The war’s polarizing effects also seem to hamper Syniy’s own ability to rise above geopolitical divides and see Russians as individuals. His narrative refers to Russians as “unrighteous people,” and he concludes it by condemning “the ruthless and bloodthirsty empire that is trying to steal home from every Ukrainian.”

More than anything, Syniy’s story captures the difficulty of education in wartime. Distraction and danger interfere, of course, with pondering lofty ideas. But more fundamentally, they interfere with the practical matter of congregating in a single space.

In August 2022, still exiled from its campus in Kherson, TCI tried starting a new academic year. The school rented a facility in Ivano-Frankivsk, a former hostel for students from India. Makeshift classrooms emerged from bare, white-walled spaces, and a small room on the second floor of a nearby church became the library.

Despite such meager facilities, TCI enrolled several dozen students in a pastor’s licensing program, and another 80 students took classes online. Meanwhile, Ukrainian forces made progress in and around Kherson. Syniy received sad news, however, on the eve of the fall semester in Ivano-Frankivsk: Russian troops had looted the Kherson campus and destroyed three of its buildings.

In November, Syniy and his wife were visiting US churches when he learned that Ukrainian forces had liberated Kherson. Yet two weeks later, his joy over the city’s rescue turned to sorrow when he visited the now-devastated TCI campus. He writes,

I remembered how we had dreamed of having a library built, how carefully we had selected books to fill it, and now everything of value to us was burned inside, scattered around, or taken away by the occupiers.

Syniy cut his tour short, fearing Russian snipers. As he recalls, “I had never felt such a dense and overhanging silence over an empty campus.”

Serving God Under Siege is an engaging window into a community of Christians upended by circumstances beyond their control. Written early in a war that still rages, the story has no certain outcome.

Perhaps TCI will rebuild and flourish in the future. But in the meantime, the school is committed to adapting as best it can amid the hardships of war. “We must fulfill our mission regardless of where we live or what resources we have,” Syniy concludes. “But I’ll tell you honestly, without infrastructure it is a much tougher challenge!”

Rick Ostrander is executive director of the Michigan Christian Study Center in Ann Arbor, Michigan. He is the author of Academically Speaking: Lessons from a Life in Christian Higher Education.