This piece was adapted from CT’s books newsletter. Subscribe here.

The Body Teaches the Soul: Ten Essential Habits to Form a Healthy and Holy Life

HarperCollins Children's Books

272 pages

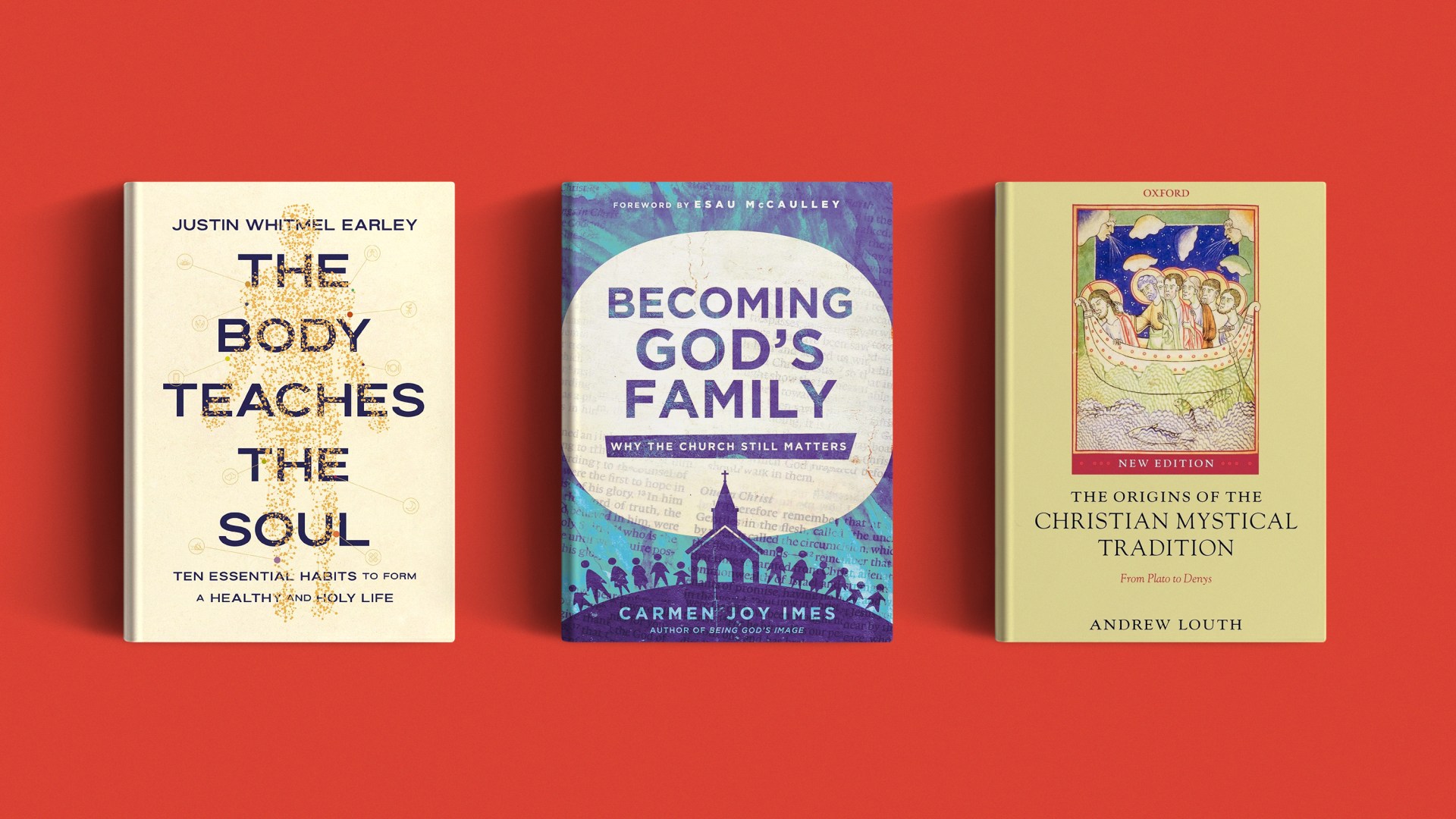

Justin Whitmel Earley, The Body Teaches the Soul: Ten Essential Habits to Form a Healthy and Holy Life (Zondervan, 2025)

When I was in high school, I was taught that the key to spiritual vitality was having a “quiet time,” which meant getting alone with God to read Scripture and pray. I am thankful for this practice, which is still foundational for my life with God. But as I’ve grown older, I’ve also felt the limitations of this approach. Prioritizing contemplation, I’ve often failed to appreciate the significance of my body. Prioritizing personal devotion, I’ve often undervalued the importance of the body of Christ.

Justin Whitmel Earley argues that rather than idolizing or ignoring our physical bodies, we should seek to image God through them. His title is a nod to Bessel van der Kolk’s popular book on trauma, The Body Keeps the Score. Like van der Kolk, Earley frames recovery as a matter of both training and healing. We can “garden” our bodies to lead our souls in the right direction, and this is a matter of attention as much as action. As he puts it, “To live with close attention to your body is to live with close attention to your soul.” To this end, Earley combines biblical reflection with scientific research to prescribe ten domains of bodily attention.

Beginning with breath, he discusses what it means to integrate the brain and shows how exercise can lead to “antifragility” (where stress makes us stronger). Along the way, he gently reorients dysfunctional habits related to food, sex, rest, and technology. But Earley’s book is no endorsement of wellness culture or our endless quest self-optimization; my favorite chapters were about reckoning with illness and remembering death. Sickness and death are unavoidable reminders of a broken world, but also of the Christian hope—“the redemption of our bodies” (Rom. 8:23).

Carmen Imes, Becoming God’s Family: Why the Church Still Matters (IVP Academic, 2025)

If Earley writes to convince readers that the Christian life is “a habit project” rather than a “head project,” Carmen Joy Imes shows that it is also a group project. In her book, she layers a powerful, cumulative case that God’s plan has never been simply to save solitary souls but to gather together a new family “from every nation, tribe, people and language” (Rev. 7:9). Extending the project of two earlier books (Being God’s Image and Bearing God’s Name), she offers a fresh retelling of the biblical narrative, cast in familial terms: family trauma (the exile), family reunion (the coming of Christ), and the family business (making disciples).

Imes is clear-eyed, deftly naming the failures of God’s family, from the mistreatment of Hagar by Abraham and Sarah to the misguided project of Christian nationalism. And yet, she writes with a hope rooted in the gospel, which allows us to glimpse God’s glory “at work in ordinary gatherings made up of all sorts of people.” Imes challenges Christians to find their home in the household of God, where God’s people gather to wait for God to do what only God can do.

Andrew Louth, The Origins of the Christian Mystical Tradition: From Plato to Denys (Oxford University Press, 1980)

Andrew Louth’s book is older and does heavier theological lifting, the sort we might expect from an early church scholar. Nevertheless, Louth’s historical excavation underwrites the arguments of Imes and Earley in significant ways. Tradition is a complicated term, yet there is a reason why Louth’s book is found on theologian Sarah Coakley’s shortlist of essential works of recent theology.

Louth shows how early church fathers wrestled with and resisted the development of a solitary and elitist spirituality, where “God and soul” are the only things that matter. To be sure, these Platonic streams exert a powerful gravity on Christian mysticism, one that lingers to the present day.

Louth concludes that the Fathers undermine “any tendency towards seeing mysticism as an elite, individualist quest for ‘peak’ experiences.” The spiritual (mystical) life is irreducibly embedded in the community of the church, and nourished by bodily practices that orient everyday experiences, not extraordinary ones.

We should keep getting alone with God, as Jesus did (Luke 5:16); but life with God includes so much more than “quiet times.” Spiritual vitality can never be purely “spiritual” or a solitary pursuit. It is something that can only occur as disciples pay attention to their bodies and find their place together in the body of Christ.

Justin Ariel Bailey is a professor of theology at Dordt University. He is the author of Interpreting Your World: Five Lenses for Engaging Theology and Culture.