This piece was adapted from CT’s books newsletter. Subscribe here.

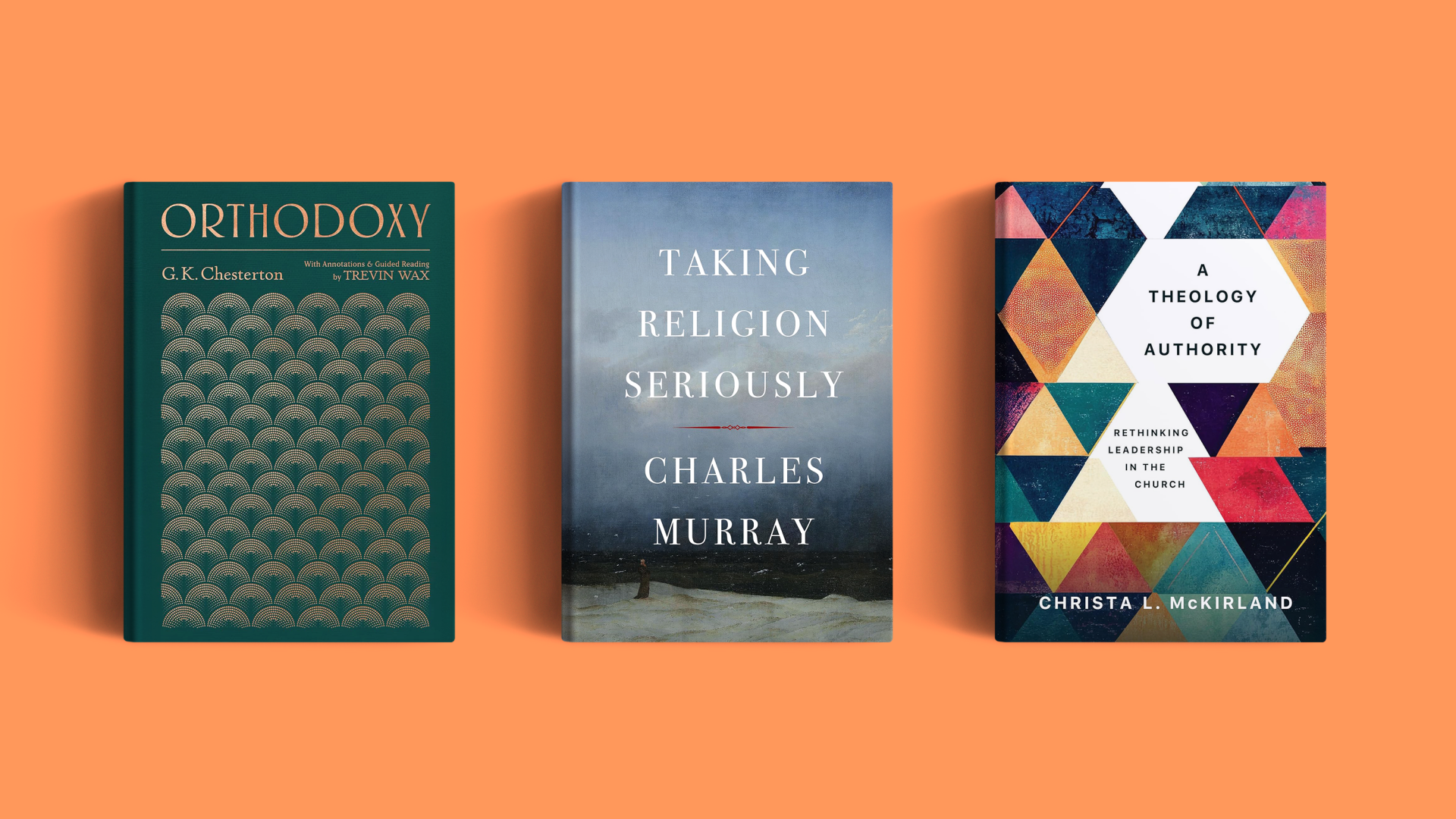

Christa McKirland, A Theology of Authority: Rethinking Leadership in the Church (Baker Academic, 2025)

The strongest parts of Christa McKirland’s book relate to the title: “a theology of authority.” With care and precision, McKirland examines a wide variety of ways in which authority functions, from God’s authority over creation to mankind’s over each other.

A lecturer in systematic theology at Carey Baptist College in New Zealand, McKirland engages seriously with a wide range of biblical examples and contemporary scholarship, makes a host of valuable distinctions about authority—executive and nonexecutive, imperative and performative, epistemic and exemplary, structural and charismatic, and so forth—and gradually assembles an impressively clear recurring diagram that summarises the entire argument. At times I would have expected a stronger link between authority and authorization, with the question of who authorizes whom playing a more prominent role. But her conceptual work is clear, rigorous, illuminating, and helpful.

The weaker parts of the book relate to the subtitle: “rethinking leadership in the church.” Those who share McKirland’s more Baptistic, egalitarian, and democratic convictions on ecclesiology will find reinforcement. For those who do not, however, there is little engagement with the relevant biblical material or counterarguments.

What actually happens when we lay on hands to appoint elders? (Surprisingly, 1 Timothy 5:22—“Do not be hasty in the laying on of hands”—is not even quoted in the book.) Is the authority Paul gives to Timothy to confront false teaching really unique, as she argues, given 2 Timothy 2:2 and Titus 1:9 (which are not quoted either)? How are the Old Testament offices of prophet, priest, and king understood and modified in the New Testament? What implications does all this have for sacramental practice? Guarding sound doctrine? Ordination? Church government? In short, McKirland’s book is a good conceptual analysis of authority combined with an underwhelming argument for a particular view of church leadership. It may divide the crowd.

Charles Murray, Taking Religion Seriously (Encounter Books, 2025)

In some ways, Taking Religion Seriously is an apologetics book that ought not to work. It feels too short and idiosyncratic to be rigorous and too dense for the mass market. The author is a deeply controversial public intellectual who has “yet to experience the joys of faith” and talks more about paranormal phenomena, near-death experiences, and the Shroud of Turin than you might expect.

Much of the book consists of arguments drawn from other writers who have addressed such subjects with more expertise—Francis Collins, Martin Rees, Rodney Stark, C. S. Lewis, Richard Bauckham, Tim Keller, and so forth—and those who have read a lot of apologetics will find nothing here that has not been said before, often better. Yet I loved reading it.

Murray’s arguments are well summarized and the quotations well chosen. He moves quickly and vividly through a series of disciplines including mathematics, physics, history, moral philosophy, and biblical studies. He represents a type of person Western Christians have often struggled to reach with the gospel—a privileged, educated person who has “not felt the God-sized hole” because, as he says, “I’ve been able to ignore it” due to the “unreflective secularism of our age.”

And he writes with disarming humility: “I don’t want to be thought credulous and foolish and get kicked out of the tribe. If you find yourself reluctant to give up strict materialism for similar reasons, try to get over it.” Most of all, it is always delightful to hear how someone came to Christ, even if (or especially if) that person’s journey was very different from our own. The result is intriguing and often heartwarming.

G. K. Chesterton, Orthodoxy (1908)

“I did try to found a heresy of my own,” says G. K. Chesterton in the opening of this magnificent book, “and when I had put the last touches to it, I discovered that it was orthodoxy.”

There are many reasons to adore this book. Chesterton is one of the genuinely great writers of Christian modernity, with an ability to craft sentences and paragraphs that provoke laughter, puzzlement, and wisdom in equal measure. His observations have the familiarity of a stand-up comedian alongside the challenge of a preacher. He is a master of paradox with a purpose, to describe, defend, or debunk. Today, he reads like a critic of modern progressivism despite writing more than 100 years ago. And Orthodoxy is his best work, an apologetic for traditional Christianity that has lost none of its provocative freshness and humor over the last 12 decades.

At its heart is the thrill of Christianity, in contrast to the dullness and torpor of contemporary alternatives. Chesterton’s God is captivating. His doctrine sparkles. His Jesus is every bit as attractive to some and infuriating to others as the one we read about in the Gospels. His ecclesiology is enticing, even when he is poking at exactly the sort of churches I love.

A few years ago, I went through Orthodoxy in a small group with people in my church. They very rarely read old books, let alone old Christian books, and I was delighted by how accessible and fascinating they found it. Do yourself a favor and follow their example.

Andrew Wilson is teaching pastor at King’s Church London and author of Remaking the World: How 1776 Created the Post-Christian West. Follow him on Twitter @AJWTheology.