In one of his dark epistles, the devil Screwtape tells his nephew Wormwood that Satan has managed to deceive humanity by convincing scholars to adopt the “Historical Point of View.”

“The Historical Point of View, put briefly, means that when a learned man is presented with any statement in an ancient author, the one question he never asks is whether it is true,” C. S. Lewis’s character explains.

And since we cannot deceive the whole human race all the time, it is most important thus to cut every generation off from all others; for where learning makes a free commerce between the ages there is always the danger that the characteristic errors of one may be corrected by the characteristic truths of another. But thanks be to Our Father [Satan] and the Historical Point of View, great scholars are now as little nourished by the past as the most ignorant mechanic who holds that “history is bunk.”

As I think back on my graduate education in history, I realize that my own attitudes toward the past were for a while perhaps uncomfortably close to this devilish perspective. Like the scholars Screwtape describes, I learned the art of researching the past using primary source documents. I enjoyed immersing myself in the texts—but I didn’t necessarily look to them for wisdom.

John D. Wilsey’s God and Country encourages Christians to adopt a more spiritually mature attitude toward the past. Like Lewis, Wilsey knows that if we’re not “nourished by the past,” we will be more vulnerable to the Devil’s lies. And like Lewis, he wants Christians to avoid the errors of uncritical nostalgia on the one hand and unreflective dismissal on the other.

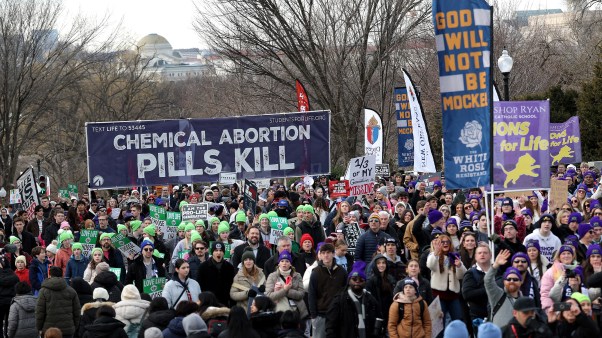

Both dangers are certainly with us. Wilsey writes in the wake of a movement on the left to tear down statues of past heroes because their actions were out of step with our contemporary moral code. He also writes at a time when an uncritical, reactionary celebration of the Confederacy is alive and well in some circles on the right.

And he writes at a time when numerous other Christians question why they should study the past at all. As a church historian teaching at Southern Baptist Theological Seminary, Wilsey notes that many of the aspiring pastors in his classes wonder why they need to take time away from their biblical and theological studies to study Christian history.

God and Country explains both why Christians should study the past and how they should do it.

Thinking about the past is part of being human, Wilsey asserts: “Humans are the only creatures that have an awareness in time.” We make memorials and tell stories about days gone by. We were “fashioned by [our] Creator” to “think historically,” he writes.

Though remembering the past is a universal phenomenon, Christians have another reason to study history. Without an awareness of what’s already happened, we won’t be able to understand God as the author of history. Christianity is not a set of moral teachings, parables, or wise principles that can be divorced from a historical context. It is instead the story of God’s redemption accomplished through a divine intervention in time and space. “Our faith and confidence in God are rooted in what He has said and done in the past,” Wilsey says. “Thus, the option of considering history as irrelevant is not open to the Christian.”

After making the case for history’s necessity, Wilsey instructs his readers in its study. His first two chapters on the subject present material that will probably be familiar to most professional historians. Students of history, he writes, must consider the “five Cs”: change over time, context, causality, contingency, and complexity. In other words, studying the past is not simply describing what happened but instead examining why particular events occurred and how they relate to other developments.

On that point, few historians would disagree, whether they’re atheists or believers. But Wilsey then pivots to suggest something I never encountered in my historiography classes at secular institutions. To study the past, he argues, we need to cultivate virtue, since “without virtue in the study of history, there is no fear of God; thus, there can be no understanding.”

Specifically, Wilsey argues that we need to develop love for the people whose lives we examine—not a mandate to like them personally, let alone excuse their flaws—but to treat them with charity in accordance with 1 Corinthians 13. Because “Paul wrote that love is patient,” we must bear with our historical subjects “in their manifold expressions of their fallenness,” Wilsey says. “We must be fair to them and their times,” he encourages. “Our place in relation to them is as their student rather than their judge.”

“Ever since the Enlightenment, it has been common to regard the people of the past as boorish, childish, superstitious, brutal, and prejudiced,” he continues. But “love excludes arrogance toward others in the present and the past.” If we cultivate Christian virtue, we won’t be “chronological snobs.”

And if we learn to love the people of the past, with all their flaws, we will find it easier to love people in the present who also are deeply flawed.

One of those present loves Wilsey says we need to cultivate is love for country. He devotes the last chapter of his book to a rightly ordered Christian patriotism, grounded in an understanding of the country’s history. An unreflective celebration of America might be jingoistic idolatry. But a Christian student of history can love America for the good it has done while lamenting its failures. Just as we can learn to love people in the past even with all their faults, so we can learn to love our country even when it has not lived up to its ideals.

It is this last chapter that is likely to raise the greatest controversy among some Christians. At least on a surface level, it’s hard to disagree with most of what Wilsey says in this book. What Christian historian, after all, would say we shouldn’t treat our historical subjects fairly and charitably? What Christian historian would say we shouldn’t consider context when studying the past?

But some Christian historians may resist Wilsey’s conclusion, at least in part. I have attended enough conferences to know that many believe historical study should be a quest for truth and justice, in the sense that we should seek to expose the wrongs of the past in order to right them in the present.

Some of these Christian historians, I imagine, would not necessarily agree with Wilsey’s assessment that “the United States is a story of the advancement of freedom, not only within our borders but around the world.” He proclaims, “No other country has done more for the advancement of human freedom than the United States.”

For those who believe that the United States is a flawed—but still mostly admirable—country, with an unparalleled record of advancing human freedom, it makes sense to love the nation despite its missteps.

On the other hand, for those who believe, as Nikole Hannah-Jones argues in the New York Times’s 1619 Project, that “anti-black racism runs in the very DNA of this country,” it may be harder to take such a sanguine view.

Wilsey is honest about America’s history of racism and slavery. But at the same time, there’s a distinct difference between his view of America as a bastion of freedom despite its racist sins and Hannah-Jones’s view of America as a society founded on racism despite its promise of liberty and equality. I’m not sure the theological work Wilsey does in this book can fully address that gap, because the gap is not simply a matter of theology but rather a matter of historical interpretation.

Even so, I hope even those who are most critical of Wilsey’s traditional conservatism and love for the United States will learn from his theological opposition to what Lewis called “chronological snobbery.”

If we find ourselves quick to denounce earlier generations who defended slavery or engaged in other morally objectionable actions, perhaps we should ask ourselves if we are treating our historical subjects with love and understanding. If we look to the past only to champion the oppressed and further our own agendas in the present, perhaps we should ask whether we’re cutting ourselves off from needed sources of wisdom.

In other words, perhaps we should ask if we’ve fallen for Screwtape’s devilish agenda.

With Wilsey’s book as a guide, readers will be less likely to succumb to this error. And maybe in the process, we’ll also become better practitioners of the Christian virtues, capable of extending grace to others—both those who lived in the past and those who are with us now.

Daniel K. Williams is an associate professor of history at Ashland University and the author of The Search for a Rational Faith: Reason and Belief in the History of American Christianity.