This piece was adapted from the Mosaic newsletter. Subscribe here.

I don’t remember Martin Luther King Jr. being the paragon of Black leadership in my home growing up. I did not go to church regularly or think deeply about Christianity, where King received a decent portion of his appreciation.

My family’s conversations instead mirrored those of the Black Panther Party. We talked more about Malcolm X, Langston Hughes and the Harlem Renaissance than about the Civil Rights Movement and King. It wasn’t until my teenage years, when my father became a Christian in a Missionary Baptist church, that peace, love, and consideration for neighbors became part of our household lexicon. I was a revolutionary-minded young man with a Swahili name, now asked to love the descendants of colonizers, slaveholders, and cultural appropriators.

My view of King back then was like my view of Jesus: I saw both as honorable men who asked their followers to practice the unconscionable act of loving their enemies. I wanted no part of either. Though I appreciated Jesus himself, I had read and listened to enough to know that many of his followers used his teachings to promote slavery and support white supremacy. Then there was King, who, despite being a decent man, struck me as an obstacle to significant revolutionary change.

When I converted to Christianity in college, my view of both changed. Amazing epiphanies happen once you remove your gaze from propagandistic portraits to their actual words. The more I listened to King, the more my appreciation grew. I came to see there is no weakness in loving your enemy, only weak interpretations of the act.

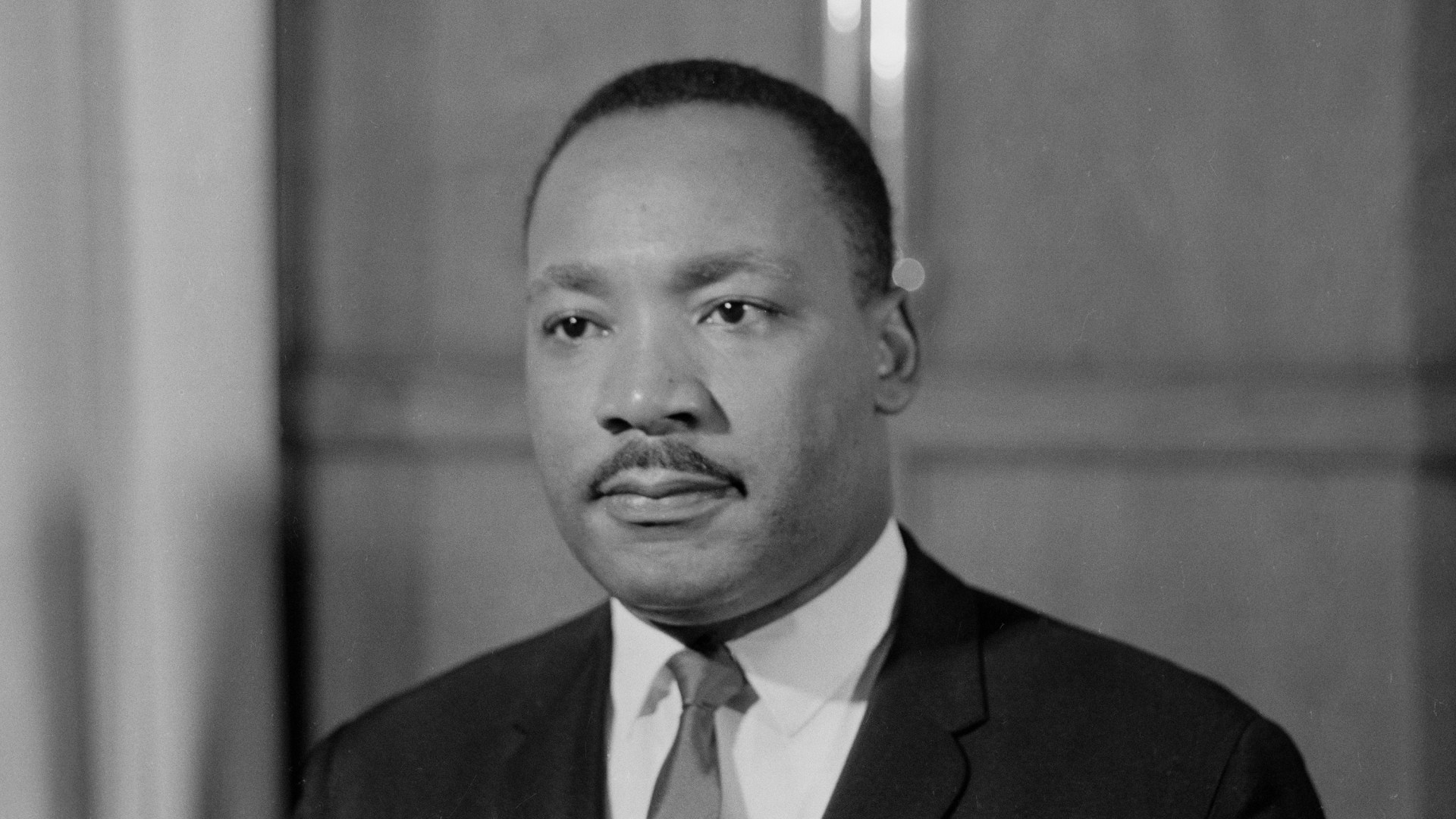

It’s fair to say many Americans have strong opinions on King with weak information. Many revere him. But nowadays, prominent voices are also unashamedly deconstructing his legacy for their own political ends. As those voices grow louder, we—both as Americans and as Christians—should stop viewing King simply as an “icon to quote” but as a complex man who should be studied and known.

In contemporary conversations about King, there are three prominent portrayals of the civil rights leader: King as the “colorblind reconciler,” the “conscious reformer,” and the “civil rights charlatan.”

Many who view him as a colorblind reconciler put emphasis on his teachings of love and nonviolence. They see him as a man who not only avoided focusing on race but also wouldn’t dare associate himself with the contemporary antiracist movement and thinkers of today—primarily, according to this camp, because of antiracists’ race-baiting. But much of the public commentary from the political right, where the colorblind view is dominant, can go in different directions. Was King a champion of colorblindness, or was he the architect of destructive DEI (diversity, equity, and inclusion) policies as the late Charlie Kirk and others believed?

Then there is King as the conscious reformer—the view that dominates most of American society. Most Americans believe that King is an earnest leader who instituted significant political and spiritual change and that his prophetic critiques of racism held up a mirror to an immoral democracy. Many also appreciate his criticisms of both militarism and capitalism.

The strongest critique of this view, however, comes from leftists who argue King’s methods of “respectability politics” did not go far enough. Author Harold Cruse, for example, suggested in his book The Crisis of The Negro Intellectual that Black intellectuals like King are equally to blame for the lack of progress in America. Cruse, a Black nationalist, falsely saw King and others as individuals who occupied their hands with picket signs rather than engaging in radical solutions to America’s problems. He goes on to argue that this approach led many Black intellectuals to get what they truly wanted: assimilation rather than revolt.

Lastly, we have King as the civil rights charlatan. In the spirit of Bull Connor, people who hold this view scoff at King’s Christian rhetoric as pure lies from a communist adulterer. They might say they have finally gained the moral clarity to reject the sentimentality of King’s poisonous gospel. As writer Stephen Prager notes in his Current Affairs article, those who hold this view on the political right “are not just trying to alter the record on King—they have begun to make the case to roll back his legacy.” In a nutshell, they are sick of some Americans pulling down their statues, so they will attack yours in return.

I have little patience for this portrayal of King, especially coming from pundits who put their support behind immoral political leaders and extol the greatness of known racists and insurgents while reshuffling history to present them as patriots.

It goes without saying that King was a flawed human who tried his best to call a nation to repentance. It’s highly probable that he lived his own Davidic life as a selfless servant after God’s own heart. His private indiscretions can’t be ignored. However, as my brother Dhati Lewis says, “The Christian isn’t marked by the absence of sin but by the presence of love” (John 13:35). And I believe King had love.

At the age of 26, King led the Montgomery bus boycott and was assassinated just 13 years later. It’s a complicated task to wrestle down the totality of his short life into an accessible ideology. Like King, many of us have changed or altered our views significantly over the course of 13 years. I am embarrassed by some of the things I espoused in my 20s. People could have labeled me many things. But thank God I have reached a new decade to push new ideas, some of which I will probably abhor in my 50s.

So, what then shall we do with the icon we celebrate every January?

When it comes to King being a proponent of respectability politics, Harvard professor Brandon M. Terry would say, “King never entertained the indefensible respectability-politics proposition that blacks must ‘prove’ themselves fit for equal citizenship. His politics are better described as a politics of character.” That said, it is true that King would consider today’s sexual deviancy as a psychological problem. That, in my view, is far from a radical’s position.

When it comes to the view that King was a race-baiter, that is also wrong. King believed all men were created “equal in intrinsic worth” and denounced supremacy of all kinds. “Black supremacy is as bad as white supremacy,” he said in a 1959 address. “God is not interested merely in the freedom of black men and brown and yellow men, God is interested in the freedom of the whole human race.” Even though he believed everyone was equal, he also noted some individuals “do excel and rise to the heights of genius in their areas and in their fields.” This is far from a cultural Marxist.

King did not wholeheartedly support reparations. But he “proposed a government compensatory program.” He called for a redistribution of wealth in the form of democratic socialism. He often critiqued capitalism, but he stated that communism lacked the “kingdom of brotherhood.” He also believed policies that addressed the poor would benefit the Black population, something that doesn’t fit the profile of a simply docile colorblind reconciler.

It’s easy to say Martin Luther King Jr. was complex. As I’ve been told, you don’t know a book until you’ve read it multiple times. And we have not read King enough. I don’t hope for a moratorium during our latest celebration of his life. But I do hope for people who know little about his actual beliefs to stop speaking with a level of certainty about him.

Personally, even after reading King’s many writings, listening to a plethora of his sermons and speeches, and even writing a musical about the 1968 sanitation workers’ strike which led to his assassination, I still don’t think I properly know King.

But I am confident in saying that the principles he taught and the way he taught them puts him in a class that is second to none. And now more than ever, America needs him. There aren’t many things Americans agree on. If King’s detractors succeed in presenting his public life as a democratic failure, our moral imagination will kick over a pillar that has been upholding an already-faulty house.

Sho Baraka is editorial director of the Big Tent Initiative at CT.