Is there a connection? Historians press – perhaps too hard – for answers.

Priscilla Du Preez / Unsplash

Priscilla Du Preez / UnsplashThis is a belated report from the American Historical Associa-

tion/American Society of Church History conference, held in New

York City the first week of January. Excellent sessions on American religious history abounded, with a surprising number of them scheduled on the AHA program. My hunch is that this abundance has something to do with the relative scarcity of American Christian history on the program at the American Academy of Religion, the other major conference for scholars in this field, but that’s my own professional bugaboo, not worth ranting about here.

Anyhow, I’d like to focus on one AHA session, titled, “Oil, Coal, and Conservative Religion in the Twentieth Century.” (In the interest of full disclosure, I worked with four of the five scholars involved with this session at Duke or the University of North Carolina, so I’m not exactly choosing it at random.)

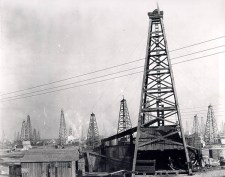

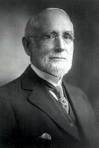

The first paper, by Brendan Pietsch at Duke, dug into the mind of Ly-

man Stewart, the early twentieth-century oil tycoon who bankrolled

Not long after Diane Langberg began working as a clinical psychologist in the 1970s, a client told her that she had been a victim of sexual abuse at the hands of her father. Not sure of what to do, Langberg went to talk to her supervisor.

Not long after Diane Langberg began working as a clinical psychologist in the 1970s, a client told her that she had been a victim of sexual abuse at the hands of her father. Not sure of what to do, Langberg went to talk to her supervisor.The supervisor, Langberg recalled, dismissed the allegations.

“He told me that women make these things up,” Langberg said. “My job was to not be taken in by them.”

The supervisor’s response left Langberg in a dilemma. Did she believe her client? Or did she trust her supervisor’s advice?

“The choice I made is pretty obvious at this point,” the 74-year old Langberg said in a recent interview.

For the last five decades, Langberg has been a leading expert in caring for survivors of abuse and trauma. When she began, few believed sexual abuse existed, let alone in the church. Churches were seen as a refuge for the weary and some of the safest places in the world.

Today, she said, there’s much more awareness of the reality of sexual abuse and of other kinds of misconduct, especially the abuse of spiritual power. Still, many congregations and church leaders have yet to reckon with the damage that has been done to abuse survivors where churches turned a blind eye to the suffering in their midst.

“We have utterly failed God,” she said. “We protected our own institutions and status more than his name or his people. What we have taught people is that the institution is what God loves, not the sheep.”

The daughter of an Air Force colonel, who grew up attending services in a variety of denominations, Langberg still has faith in God. And she remains a churchgoer, despite the failings of Christian leaders and institutions. Still, she said, those churches and institutions have a great deal to repent of and make amends for.

Langberg, author of Redeeming Power: Understanding Authority and Abuse in the Church, spoke with Religion News Service about the sex abuse crisis in the Southern Baptist Convention, what lessons she’s learned over the past five decades and why she keeps the faith despite the church’s flaws.

This interview has been edited for clarity and length.

When it comes to sexual abuse, there are a growing number of church leaders who say, “We get this now and we can fix it.” But are they aware of the long-term consequences that come with mishandling abuse allegations over a long period of time?

Perhaps it would be helpful to first think about not the church but marriage. If somebody has an affair, they cry and say they are sorry. Then a year later, they have an affair with somebody else. How many affairs are going to be OK before you leave?

That is the kind of thing that has happened regarding the Southern Baptists. This has gone on for a really, really long time. And now they want to say they get it. It’s too soon. Even if they were doing absolutely everything they could to get it. It’s too soon.

How can church leaders start to regain trust?

The first step is not asking for it. The first step is to say, “I want to know what this has done to you. I want to know the ways that it’s been hurtful, I want to really understand the depths of what we did, and how it affects you, not just in terms of church, but in terms of understanding God himself.” To realize that this person whom God loves has been damaged by us who represent God. And we can’t fix that.

We have utterly failed God. We protected our own institutions and status more than his name or his people. What we have taught people is that the institution is what God loves, not the sheep.

What have you learned in 50 years of this work?

I don’t think we really understand the level of deception that occurs in people who abuse. We think that if they cry and say they are sorry, that’s a good thing. But it doesn’t touch the practice of deception that runs their lives and that runs their organizations. We’re very naive about that. You can’t marinate yourself in the lies and deception that are needed to keep abusing—and then say “I’m sorry” and have that change who you are.

There’s been a growing awareness about the dangers of the abuse of children and a willingness to address that issue on the part of churches. But many churches have a difficult time with the idea that adults can be abused. There’s an idea that if you are an adult, then a pastor can’t abuse you.

I find that outrageous, to put it mildly. The word “abuse” means to use wrong. I don’t think we understand the power that comes with the position of being a pastor. I mean, do we really think pastors can’t abuse that power? That they’re above this?

That’s a ridiculous thought about any human being. We’re all sinners. We’re all deceptive. We all deceive. To say just because somebody is a pastor means they can’t be abusive is naive.

If you had a group of Southern Baptist leaders right now in front of you, what would you tell them?

I would tell them that the first thing they need to find is humility. You can’t do something wrong for decades and then say, “Oh, we’re sorry, we did it wrong”—and think that now you understand it. It’s not possible for any human. You can’t cry and say you are sorry and ask for forgiveness and then it’s all fixed. My reading of the Scriptures and how sin gets ahold of us, and blindness gets ahold of us, would suggest that’s way off the mark.

What have you learned from survivors of abuse?

We don’t realize the level of courage that has been displayed right in front of us. Particularly in Christendom, if you tell the story of surviving abuse, you’re not only going against the person who did it, you’re going against God’s people, you’re going against his church, which adds up to going against God.

And survivors often lose their place in the church. They lose any status they had. They lose honor. They lose trust. All because of the things that were done to them.

Have you ever thought of giving up?

I cut my teeth working with Vietnam vets and with women who told me about abuse that nobody believed. The diagnosis of post-traumatic stress disorder hadn’t come out yet. So people thought vets were making it up because they were weak, and the women were making it up because they wanted attention. It was a very lonely road. And somewhere along the way, I told God I was quitting. He obviously convinced me not to do that. Then when I began to realize how much of this was in the church, I wanted to walk away. He convinced me to stay. And I’m very glad I did.

The Fundamentals. Drawing on Stewart’s writings, the paper found an alchemical link between drilling and evangelism, as Stewart repeatedly professed a desire to transmute oil wealth into “living gospel truth” as quickly as possible. The paper also sketched a link

between the breathless search for new reserves –

Stewart was known to sniff for oil in gopher holes – and a similarly exhilarating search for hidden truths in the Bible’s prophetic passages.

The second paper, presented by Seth Dowland, also of Duke, told the story of coincident school boycotts and coal miners’ strikes in West Virginia in 1974. First, angry about new language arts textbooks they called “trashy, filthy, and too one-sided,” conservative Christian parents pulled their children out of the Kanawha County public schools. A few days later, the country’s coal miners, including many from the same area of West Virginia, struck for higher wages and better health benefits. A miner who lived down the street from the head of the United Mine Workers of America told the Charleston Gazette, “I don’t think there will be anybody back to work until those textbooks are out.” Dowland went on to detail the ways two groups of disgruntled West Virginians came together in a “populist revolt that captivated the nation.”

Finally, Darren Dochuck of Purdue University elucidated the little-known career of R.G. LeTourneau, extraction industry pioneer, defense contractor extraordinaire, and founder of an eponymous evangelical university specializing in the training of engineers. Dochuck called his paper, “Extracted Truth: The Politics of God and Black Gold in Post-World War II America.” he depicted LeTourneau as a man absolutely convinced that he moved mountains of dirt for the glory of God.

Causality Crusade

Katie Lofton, soon to join the faculty of Yale University, responded to these papers. She pressed all of the presenters to identify causal relationships between the phenomena on which they reported. To paraphrase her questions, Did Lyman Stewart’s belief in an imminent Second Coming propel him into the oilfields and govern the decisions he made there? Did West Virginia coal miners really walk off their jobs because they didn’t like an English textbook? Did LeTourneau’s evangelicalism predetermine his alliance with the New Right (including the Bush family) and indifference to the environmental consequences of extraction?

In several ways, the papers begged such questions. All three had linked the energy industry and evangelicalism with an “and,” but none had stated an emphatic “because.” Additionally, each paper quoted at least one figure providing religious justification for his or her actions. The causal connection leapt out of the sources, putting the historians on the spot. If a historical actor writes that God instructed him to dig his well right here, or move that particular mound of dirt, on what grounds may a scholar argue otherwise? On the other hand, aren’t scholars expected to probe such claims? If historians cannot add context and critical analysis to the primary sources, libraries ought to trade out all of their monographs for photocopied diaries and letters.

The Suction Hypothesis

In other ways, though, the causality crusade made me uneasy, because it seemed to single out conservative religion. By way of contrast, my dissertation on The Christian Century noted that the magazine derived significant financial support from William H. Hoover of Hoover vacuum fame, but none of my readers asked me for a causal link between suction and liberal Protestantism. The re-founding editor of the Century was a Disciples of Christ minister, Hoover was a Disciples layman, and no further connection seemed necessary. Does theology always reign supreme among conservative Christians’ motivations? Does conservative – especially Fundamentalist – Christianity strike scholars as so exotic that it obscures other lines of inquiry? In short, are conservative Christians treated differently by historians than members of different traditions, and, if so, how and why?

None of this is to suggest that I found the AHA session hostile or biased. The stories told by the presenters deserve more attention, and the ensuing discussion clarified some issues while complicating others, which is exactly what academic conferences are supposed to do. I left thinking more about my own motivations and about the kinds of questions I pose to historical actors. Should I look for a link between suction (or perhaps broader subjects like cleanliness and domesticity) and liberal Protestantism? I’ll let you know if I find any.