The Nazis possess a special place in our moral imagination. We take them to be a world apart, created by a special confluence of time and circumstance that unleashed unrepeatable horrors. But this understanding obscures something important that this scale of evil may prevent us from seeing.

The Holocaust is of course singular. But many interpretations, in explaining this mass murder of Jews as the result of special psychology, historical circumstance, or political arrangement, have ended up at a misguided conclusion—that surely something like this could never happen again.

It is this question—What makes the Nazis unique?—that the new movie Nuremberg tackles. The film opens in the aftermath of the Second World War with the arrest of Germany’s second-in-command Hermann Göring as he travels with his family in Austria. As the Allies move across Europe, they document concentration camps, and with these discoveries, urgency grows: What should be done with Göring? What kind of punishment fits the systematic murder of millions of Jews, political prisoners, and people with disabilities? The film follows Göring’s subsequent imprisonment as the world prepares for the first international war-crimes trial. All the while, the Allies are unsure how to categorize actions of such moral gravity.

Nuremberg isn’t the first work to home in on this dilemma. The 1961 Judgment at Nuremberg, as well as other TV series and movies, covered the events of 1946. But this treatment has a unique psychological vantage point, drawing from Jack El-Hai’s 2013 book The Nazi and the Psychiatrist, interpreting events through the relationship between Hermann Göring and psychiatrist Douglas Kelley, who was brought in to evaluate the war criminal for trial. Quickly, in the film, the professional relationship becomes a personal crisis. Kelley, along with the rest of the world, grapples for understanding of how something like this could have happened.

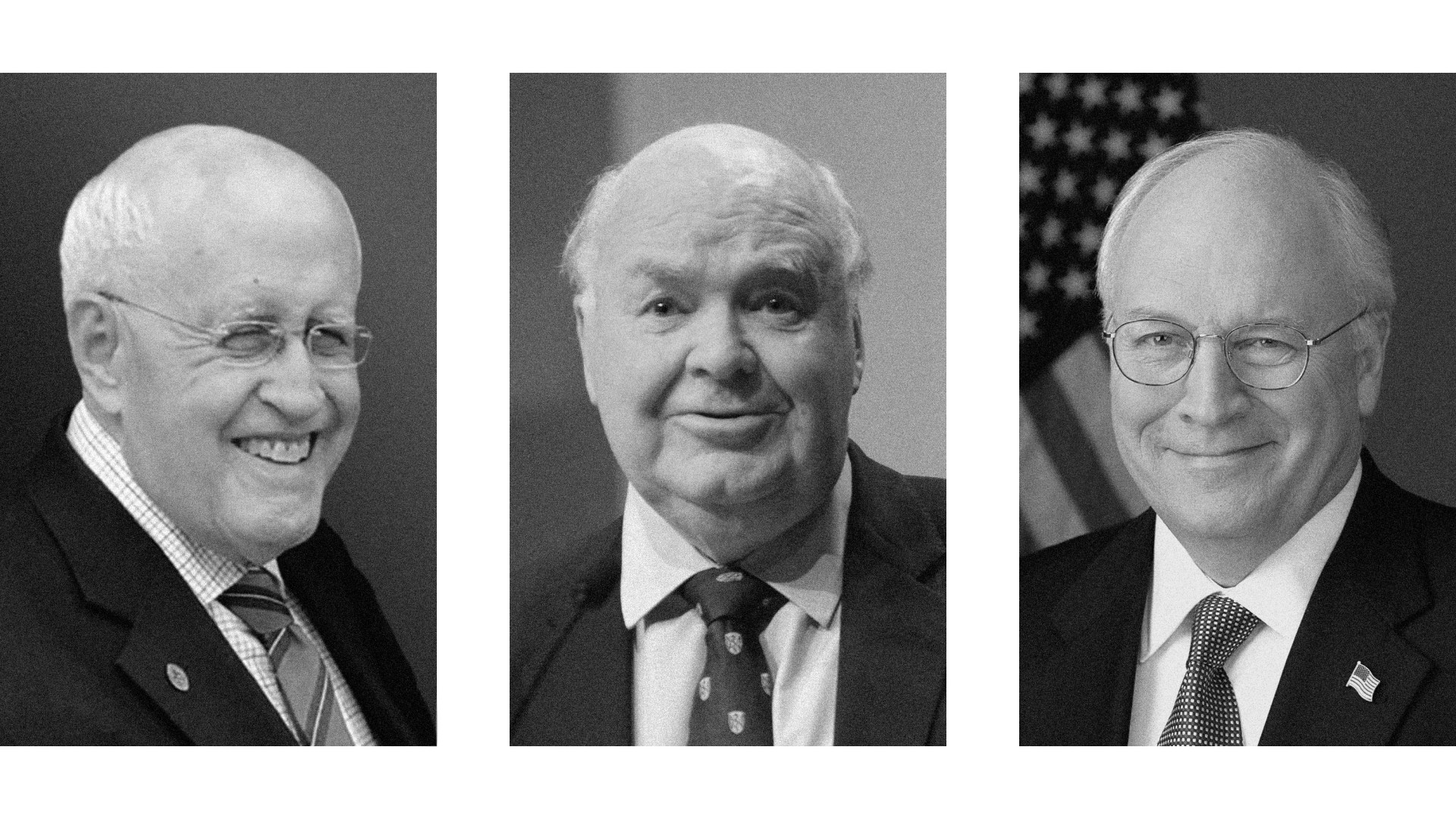

Standout performances by Russell Crowe, Rami Malek, and Michael Shannon help transform this courtroom drama into an exploration of how evil works. Driving home the graphic realities of concentration camps, Nuremberg uses archival footage compiled for the original trial. For those unfamiliar with—or debating—the realities of the Second World War, the film offers its case in flesh and bone.

But the events of Nuremberg are primarily an occasion for asking not whether the Holocaust happened but how. Kelley, the psychiatrist, begins to arrive at an answer by noting that Göring is not so much an ideologue as he is a narcissist, seeing in his own person the greatness of the Nazi Reich. His worldview comes through in the way he relates to the other defendants, imagines himself able to outsmart his captors, and touts the Nazi political program as an unassailable demand which anyone should find reasonable.

Kelley, though not a Christian, sees this hubris for its ubiquity—though he fails to convince his countrymen that the desire to make the world over in our own image is not unique to German psychology or the Third Reich’s administrative structure. Goering was proud, and pride is no respecter of time and place. Nuremberg hammers home a basic point about human nature. Pride and its resulting violence are a possible problem everywhere.

Kelley’s insight has proved to be right, in that the mass slaughter of one people by another has certainly not been restricted to the Nazis. Since the word genocide entered the world’s vocabulary in 1942, the crime it names has been repeated several times over.

These ordinary and universal vices—this pride, this desire to subjugate others to our own vision of the world—are not the property of one country or nation. So long as humans are sinners, there is no reason to suspect that any place is exempt from evil.

That lesson comes through in the film’s unexpected final act. Throughout Nuremberg, a young sergeant with particular reasons to seek revenge fantasizes about bringing the captured Nazis to justice. But after the trial, as the moment of execution draws near, his most-hated enemy breaks down in sobs, unable even to dress himself. The sergeant kneels down next to him and says simply, “I am German also.” He accompanies him by the hand to the gallows, staying with his enemy to the end.

The recognition that, in the end, the Nazis are humans—even our neighbors—transforms this story from one of pure revenge to one which invites us to grieve, both for the millions killed by the Nazis and for the denigrated humanity of the Nazis themselves. As the generation that could give firsthand testimony to the Holocaust passes away, Nuremberg is an important film to help Christians remember not only what happened but also how the evil that happened in Germany is the kind of evil that can happen again—and must be repented of everywhere it appears.

Myles Werntz is the author of Contesting the Body of Christ: Ecclesiology’s Revolutionary Century. He writes at Taking Off and Landing and teaches at Abilene Christian University.