Last week, Christianity Today began its year-by-year showing of what the magazine thought important since it began in 1956. We’ll present what CT published—warts and all, as in an item on segregation noted below. Today’s installment shows evangelical reactions to the news of 1957.

We’ll start with a small cloud on the horizon that decades later would become part of a thunderstorm. CT reported on evangelical concern about immigration and the impact a proposed bill might have on the country’s makeup.

The National Association of Evangelicals has voiced objections to Senate Bill 2410, introduced by Senator John F. Kennedy (D.-Mass.)—providing for an annual redistribution of unused quotas.

Such a provision means that quotas from such countries as England, Ireland and Germany, which are seldom filled, could be assigned to regional pools. This would give emigrants from Europe, Asia, Africa and Oceania a second chance of coming to the U. S.

Dr. Clyde W. Taylor, NAE Secretary of Public Affairs, said the bill “provides for a shift of quotas from the unused ones for western and northern Europe, that have provided our main cultural emphasis, to southern and eastern Europe, that are Roman Catholic and decidedly of minority cultural emphasis.

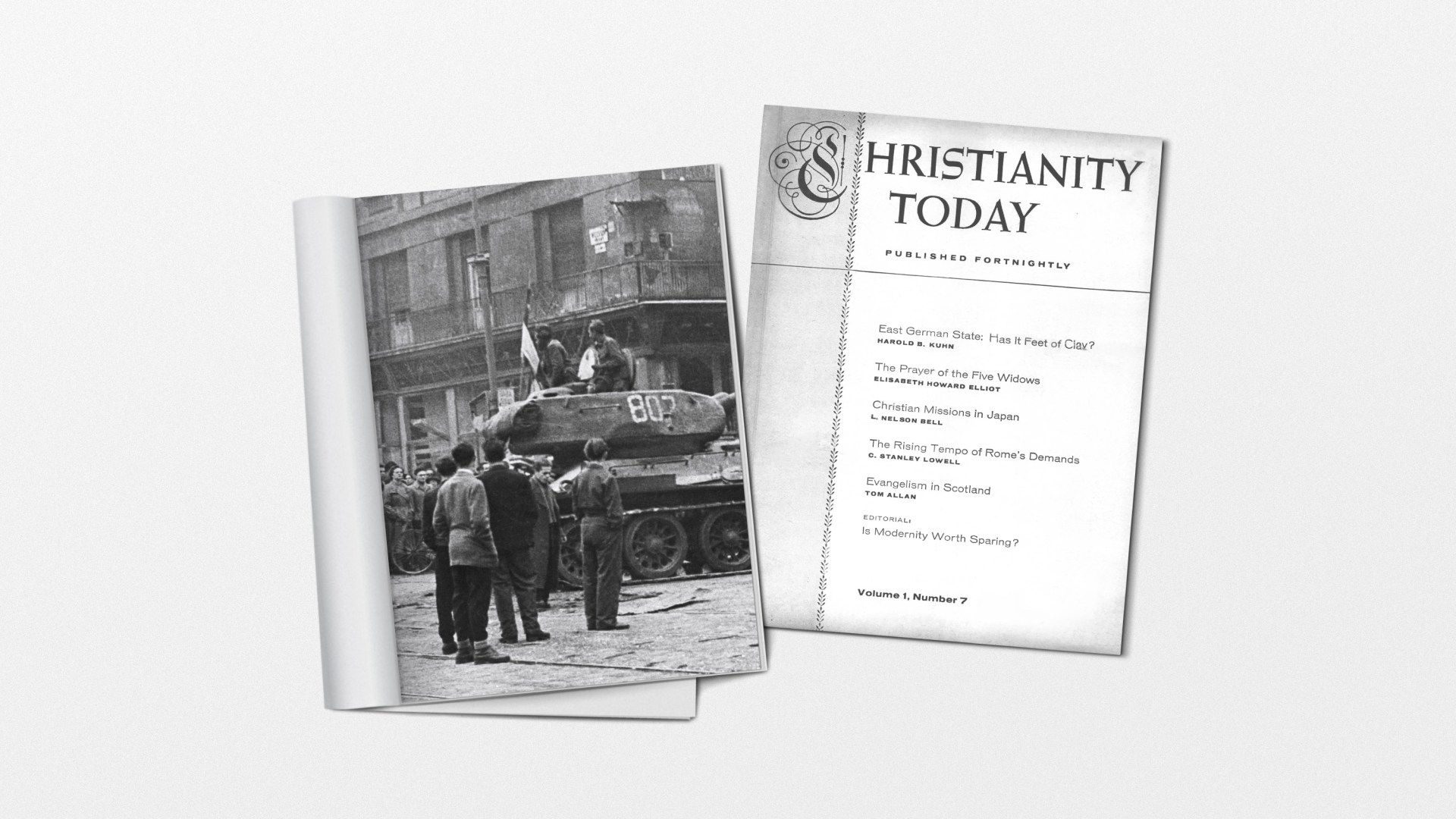

Following World War II, the victorious Soviet Army had created puppet regimes throughout Eastern Europe. CT editors wondered whether they would last. It look another 32 years for those dictatorships to fall, but in 1957 one writer asked, “The East German State: Has It Feet of Clay?” The cautious answer:

The [Communist] Party itself, hated by the masses, maintains itself in power by brute force. It rationalizes its position by posing, through endless propaganda media, as the agent of transformation, which promises a glorious tomorrow through planned and managed change. …

East Germany is predominantly Protestant. The Evangelical (Protestant) Church has attracted wide attention for its courageous resistance to the encroachments of the regime. Dr. Jacob, Bishop of Cottbus, declared in Berlin last June that the Church would accept no compromise with atheism and would resist the “theoretical and material godlessness” that underlies the dialectical materialism to which the government professes such slavish adherence. …

The larger ministry of the Church is curtailed in every way imaginable. A church may receive little or no help from the outside; it may export no funds whatsoever. While the supply of paper for atheistic literature is abundant, the publication of religious periodicals is rigidly controlled because of “paper shortages.” Home missions are rigidly curtailed; all but a handful of the Railway Missions ministering to the aged, the infirm and mothers traveling with children have recently been closed. …

If and when Germany is reunited, and if the present government of East Germany is liquidated, the question of what legacy the regime will leave behind is a crucial one. One dares to hope that such a time will reveal that the East German Church has been largely significant in keeping alive the ideas and ideals of Christian civilization during the long night of communist rule.

New technologies raised complicated moral questions. Christians in the late 1950s confronted issues of artificial insemination.

Artificial insemination (the procedure whereby a donor renders a woman pregnant through the medium of a physician’s instruments and office) today is no longer an academic question. … In the United States alone thousands of “test-tube” babies are born every year. …

The practice, of course, involves fundamental moral and spiritual considerations. … Does the method used sanction the conception of a child by a man who is not the husband of the mother? Or, in other words, is it possible that circumstances may occur when it is morally and spiritually excusable for a woman to have a child by a third party to her marriage?

Doctors and sociologists in increasing numbers say yes. They point to the impersonal nature of the arrangement; to the natural hunger of married couples for children; to the frustrations that inevitably attend a childless marriage. … They often speak of this act as a simple medical procedure which, to all practical purposes, now allows the husband himself to become a father—although the semen is not actually his.

But the fact remains that the woman who submits herself to artificial insemination has a child by a man who is not her husband. The donor, not the husband, is the true father of the child that is subsequently born. The productive union between this father and this mother is not that of husband and wife. It may properly be asked, therefore, if the infant is not, logically and literally, born out of wedlock?

On the other hand, supporters of artificial insemination point out that the procedure can hardly be called natural intercourse. And without the physical sensations associated with sex, can this be adultery?

But such attempts to justify the practice on account of the procedure employed raise other questions: If the method used to accomplish this conception and pregnancy is without moral stigma, then why wouldn’t it be morally right for any woman to have children this way, even unmarried ones? Why a husband at all? Most women crave the joys of motherhood, spinsters as well as matrons; and millions are denied those joys because they never marry. If it is morally defensible to have children via the test-tube and without benefit of clergy, then why not any woman who desires children, whether single or married?

CT also addressed racial segregation. The magazine published a pro-segregation piece—for which it later apologized—while the editors themselves wrestled with the limits of legislation and the role Christians should take in leading by example. In the “The Church and the Race Problem,” the editors wrote:

There are wrongs in the land, and the church had best be the Church, and cry against them; there is no biblical mandate to preserve the shaggy status quo. Community tolerance of violence; forced segregation in public transportation; tactics of fear and intimidation; snobbishness that looks down upon Negro Christians virtually as inferior believers; the indifference to discrimination against the Negro in America even by some churches calling for missionaries to lift the life and culture of the dark-skinned natives of Africa—these factors suggest the deep need for soul-searching and repentance in the churches.

The Church needs to recover the biblical point of view. The Church itself was born in the glory of a multi-tongued and multi-colored Pentecost. It moved swiftly to make Christian brotherhood a reality in the experience of the inhabitants of Africa and Europe, no less than of Asia and the Near East. It did not preoccupy itself with the adoption of strategically worded resolutions at the top level of councils and conventions; it put Christian love to work at the local level. The early Church unleashed a flood of kindness in a world of racial strife; the modern Church has too often unleashed a flood of resolutions. …

In its enthusiasm to do something vital, the Church falls easy prey to secular and socializing programs. It has no mandate to legislate upon the world a program of legal requirements in the name of the Church. Nor dare it disregard the existence of social rights in which the natural preferences of individuals may be expressed without compromising the legal or spiritual rights of others. Forced integration is as contrary to Christian principles as is forced segregation. The reliance on pressure rather than on persuasion has resulted in a marked increase of racial tensions in some areas. Christianity ideally moves upon the life of the community by spiritual means; the secular agencies, on the other hand, tend to resort to force, with the result that their achievements are continually endangered. Paul did not outlaw slavery legally, but he outlawed it spiritually; he sent Onesimus back to Philemon as a brother in Christ. He knew that the Church’s weapons are spiritual, not carnal; that Christian progress is not revolutionary but regenerative. And a recovery of the imperative affectionate neighbor relations, and of the Holy Spirit as the dynamic of Christian living, is still the best—and the only durable—hope for a firm solution of the race problem.

While some churches seem determined to continue with a program excluding other races, and others are thrown into internal tensions between member and member, and member and minister, still others, without fanfare and headlines, have long welcomed all converts to Christ with equal dignity and rights as members of the body of Christ. Any church should be open to believers of any race. Forced segregation, however, involves the abrogation of a citizen’s legal rights as well as his spiritual rights.

The Church by a true example of the equality of all believers may rebuke the conscience of the world. The fellowship of believers still holds a power to vitalize the fellowship of the community at large. What has compromised this power is the secularization of the churches. Let the church be the Church, and the sense of human brotherhood will be revived; the redeemed will find that their differences from each other pale alongside the fact of their unity in Christ, and that their differences from the unredeemed are less important than their common dignity and shame in Adam. The Christian is not without principles on which to base his personal relationships, and they are comprehended in the obligation of love for neighbor. A friendly smile, a kindly word, a courteous act, speak more eloquently than a press release.

A voluntary segregation, even of believers, can well be a Christian procedure. A church may be impoverished by the racial limitations of its membership and also impoverished through indifference to cultural ties. Churches in which integration is not practiced may be just as Christian as those where it is found. The determining factor is exclusion or inclusion because of race. Are the Chinese congregations of New Orleans or Chicago or San Francisco unchristian because they prefer such an alignment? Are all-Negro or all-White churches necessarily monuments to racial prejudice? And may not the publicity of the integrated church reflect an emphasis on spiritual pride as much as the unintegrated church?

The churches in America are on the advance. The searching of soul is a good sign. Little can be gained by organizational pressures; more will be gained from mutual respect and forbearance. The long sweep of history not only shows the church and individual Christians on the side of justice; it shows the content of justice itself lifted and purified by the conscience of the church. In the long run, it will be so in America also even in matters of race. Let us hope this is a decade of decision and deed.

While politics sometimes seemed important—even urgent—CT always directed readers back to the crucial work of gospel proclamation. Readers received regular reports on Billy Graham’s ministry, including his successful evangelistic event in New York City.

One of the largest crowds in Billy Graham’s New York Crusade turned out the night he delivered a special address to the thousands who had made decisions there to live for Christ. An estimated 19,000 jammed Madison Square Garden for the sermon on “How to Live A Christian Life.” …

[Billy Graham said,] “How does a Christian grow? I am going to list five ways. There are others, but these are five of the most important.

“First, a Christian grows when he prays. When you were a baby, you had to learn to walk. You learn to pray the same way. God doesn’t expect your words to be perfect. When I heard my son, Franklin, say ‘da-da’ for the first time, the words were more beautiful than any ever used by Churchill. I am going to be a little worried, however, if he is still saying ‘da-da’ when he is 12 years old. … “Every Christian should have a quiet time alone with God every day. Your spiritual life will never be much without it. …

“Second, a Christian grows when he reads the Bible. This should happen every day, without fail. … Turn off the television set and read the Bible. …

“Third, a Christian grows when he leads a disciplined life. Your bodies, minds and tongues should be disciplined. Practice self-control. The Holy Spirit will give you the strength to become Christian soldiers. …

“Fourth, a Christian grows by being faithful in his church. Going to church is not optional; it’s necessary. God says we are not to forsake the assembling of ourselves together. … Get into a good church where the Bible is preached and Christ is exalted. Get to work for God. Join a Bible study cell in your church. The communists borrowed this method from the early church and their godless doctrine spread like wildfire.

“Five, a Christian grows through service. Be a soul winner. There’s a difference between a witness and a soul winner. A soul winner is filled with the Spirit of God. He visits the sick. He gives to the poor. He loves his enemies. He is kind to his neighbors. Anyone can walk up to another on the street and bark, ‘Brother, are you saved?’ It takes more than that. We have a lot of witnesses today but very few soul winners.”

In November, CT asked evangelical Episcopal priest Samuel M. Shoemaker—widely considered one of the era’s best preachers—to write about revival and “How to Bring a Nation under God.”

What, then, should we seek to persuade America to do if we would see “this nation under God”?

First, this nation must repent. It must repent of all its arrogance, its thunderings about being better than other nations, its loss of God and the terrible consequences in crime, from crooked politicians to dopepeddlers. …

Second, let America return to its houses of worship. It is years since some of our pagan citizens have listened either to the claims of the Gospel, or its moral challenge to their lives. Church-going, for the converted, is the opportunity for the greatest exercise of which man is capable, the worship of Almighty God. …

Third, let America think and act responsibly and unselfishly. It is hard in these days to wean any act, national or personal, from elements of calculation and prudence. We need the infusion into this nation of some more simple integrity and common goodness. …

Fourth, let America seek with all its heart the faith of our fathers from which have come our chief blessings. Free nations must admit the right of any to disbelieve, to accept thanklessly the blessings which believing men have bequeathed to us which come ultimately from God. This liberty is the only way to have an uncoerced truth, a faith that is truly free. But no nation can thrive on neutrality. A wise and wary people will realize that its best leaven are the caring, creative folk who believe in God and therefore try to meet human needs as they arise.

The threat of global communism was a constant topic during the Cold War era that began when World War II ended and sputtered on until the Soviet Union ended in 1991. Americans worried when Russians leaped ahead in the Space Race by launching the first man-made satellites—Sputnik 1 and 2—taking the ideological competition into the heavens.

In 4 B.C. wise men from the East were so attracted by a strange constellation in the sky that they went out of their way to inquire of its meaning. We have reason to wonder whether the launching of Sputnik I and Sputnik II is not saying something of significance to us and we are missing the message.

Scientists tell us that it is the most significant event since the splitting of the atom. Military strategists inform us that it will change the face of future warfare. Were a rocket with an H-bomb warhead to be launched in Moscow, they say, it would destroy New York or Washington twelve minutes later. Several of these rockets could change the course of history, even extinguish Western culture. And prophetic scientists declare that if warfare were thus waged in this fashion, man could be wiped from the face of the earth. …

The message of Amos is appropos to modern America, Sputnik or no Sputnik. …

God wants America to wake up and stop ignoring his threat of future judgment. “Woe to them that are at ease in Zion, and feel secure in the mountain of Samaria … O you who put far away the evil day, and bring near the seat of violence” (6:1, 3). Like those in ancient Zion, Americans are at ease. We trust in our military defenses as much as the Israelites trusted in their natural mountain fortresses. And by concentrating on our strength, we do not even think of God as essential to our defense. …

Our entertainment-loving children are not interested in the rigorous discipline that makes scientists and men of learning. Rather than in studies, they are majoring in football. … America needs to repent for allowing the gods of pleasure and wealth, of might and wisdom, to displace the God of Holy Scripture.