The last time Benjamin Juang heard Singaporean megachurch pastor Kong Hee preach was around two decades ago.

Juang was in high school when Kong toured Taiwan in the early 2000s to promote a new album by his wife, pop star Sun Ho. Juang brought his classmates to an evangelistic concert organized by the couple, and he bought one of Ho’s albums as a gift for a non-Christian friend.

The next time he heard of Kong was a decade later, when Singaporean authorities arrested Kong for siphoning $36 million ($50 million Singapore dollars) from the megachurch he founded, City Harvest Church, to support Ho’s singing career. The church claimed the music was an evangelistic effort to spread the gospel to non-Christians, yet others questioned how such music could support the church’s mission. Kong spent a little over two years in prison for criminal breach of trust and falsification of accounts.

After his release in 2019, Kong took a break from ministry before returning to his position as senior pastor at City Harvest Church.

So when Juang, now a youth pastor at a nondenominational church in Taiwan, heard that Kong was going to be a speaker at a local conference in early May, he signed up out of curiosity. He took notes as conference organizers played a prerecorded video interview between Kong and Peter Wan, senior pastor of The Hope Church in Taipei. While Kong spoke about his past ministry failures and the spiritual renewal and rebirth he felt while in prison, Juang noticed that Kong never mentioned why he was sent to jail or expressed remorse for his actions.

“Maybe they didn’t want to shift the focus [and turn] this into an apology video,” Juang said he thought at the time. “Maybe because pastor Kong Hee had already apologized … or maybe pastor Peter told him not to mention it and focus on his personal journey.”

The video, which The Hope Church later posted on its YouTube page, racked up more than 250,000 views and stirred controversy among Chinese Christians in Singapore, Taiwan, Hong Kong, and North America. Some questioned whether Kong was truly repentant and whether it was wise for him to return to ministry. Others defended the pastor, claiming that the interview showed how Kong’s trials had led him to turn his life around.

The discussion brought out issues of repentance and prosperity-gospel teachings—topics that Chinese churches in these regions are increasingly concerned about. It also revealed ideological divides among Chinese Christians online.

Juang felt that backlash as he posted four nuanced YouTube videos in response to Kong’s interview. In one, he explained that the video interview with Wan was never meant to be an apology video. In another, to address the misconception that Kong had filled his own pockets with church money, he clarified why Kong had been sent to jail. Negative comments poured in.

“I don’t support Kong,” Juang said. “I don’t know if he’s repented yet. I don’t know if he’s as humble as he claimed. I am against the prosperity gospel. … I agree with all the other YouTubers.”

But Juang bemoans how Chinese Christians are becoming more biased and divided, “just as hateful as everybody else.”

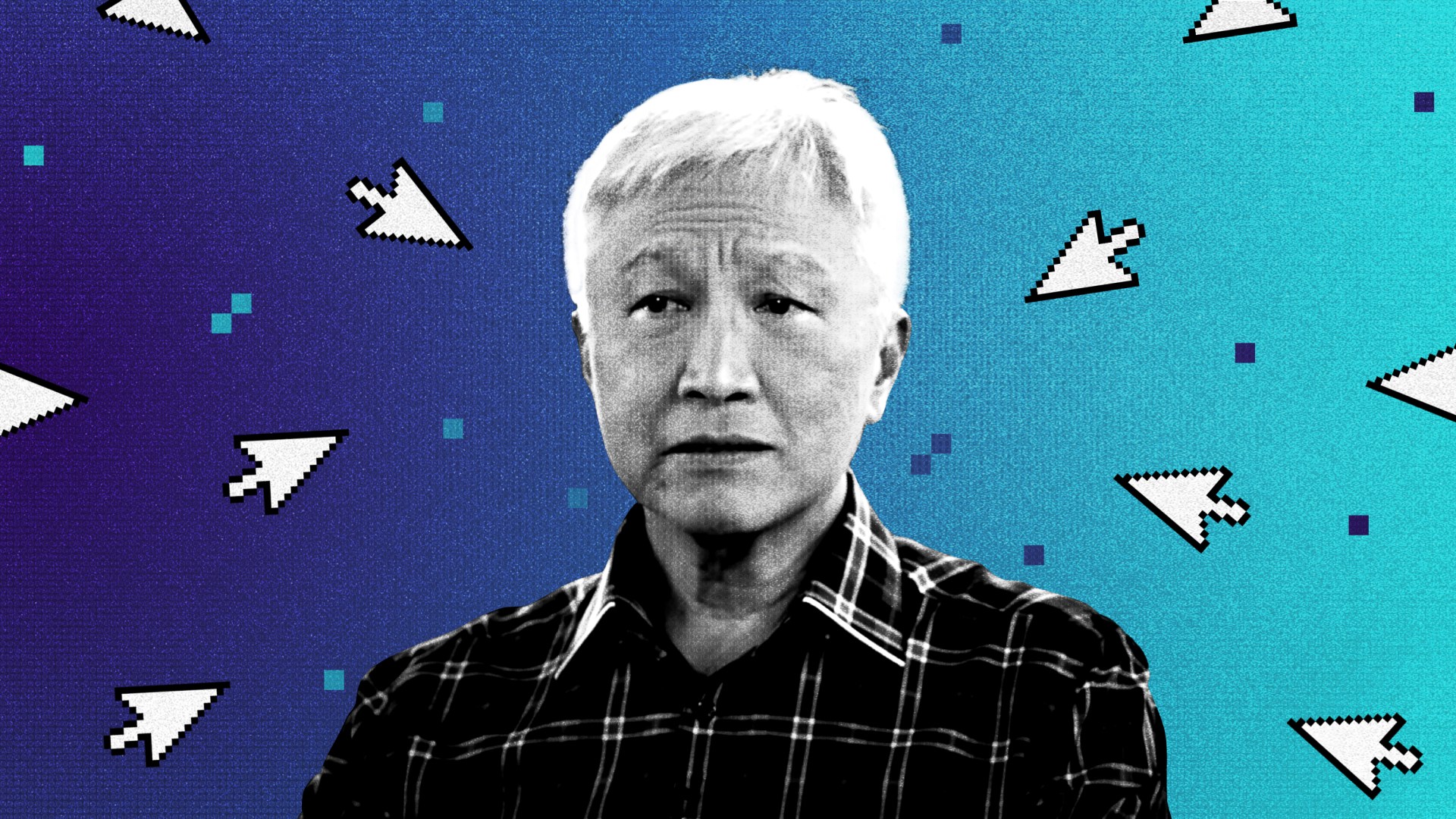

With a head of white hair and a broad smile, Kong Hee, 60, is one of the most prominent pastors in Singapore, where 18.9 percent of the population identifies as Christian.

According to the church’s website, Kong grew up Anglican and began church planting as a college student after hearing God say to him, “Kong, do you love Me more than all that the world can offer you? Will you live fully for Me and serve Me for the rest of your life?”

In 1989, he and his wife cofounded City Harvest Church with a congregation of 20 young people. The Pentecostal church, formerly part of the Assemblies of God, grew rapidly, as Singaporeans were drawn by Kong’s effusive, charismatic preaching style. At its peak in 2012, City Harvest had 33,000 congregants. Today, the church averages nearly 24,000 people each week and gathers at two locations in Singapore: a large downtown mall and a church building in the west of the city-state.

As a high school student in Taiwan, Juang thought Kong was cool. “He’s funny. He’s charismatic. … His entire presentation [was] more interesting and more geared towards younger people,” he said.

Asher Lum, a Singaporean Christian, agreed. Lum was a university student when he attended an Easter evangelistic rally in 2000 organized by the church. There he decided to believe in Jesus.

Kong’s preaching was instrumental in helping the engineer live out his newfound faith. The vibrant, energetic church was filled with young adults, and Kong’s messages often spoke about how to relate the Bible to the workplace and family relationships, Lum said.

Yet others criticized City Harvest for promoting the prosperity gospel, including claims that congregants who gave larger tithes would receive more blessings in their lives, such as job promotions.

To better reach young people, Kong and Ho launched the Crossover Project in 2000 with the goal of using secular music to “communicate the love of God to unchurched youth,” according to City News, the church’s in-house publication. Kong said the idea came to him when he visited Taiwan and noticed that although hardly any young people attended church, many would show up when Ho sang familiar pop songs.

Ho’s first Mandopop album debuted in 2002, and she went on to record four more albums with Warner Music Taiwan, with several albums reaching double or triple platinum. Later, Ho released English-language singles like Fancy Free that reached the top of Billboard’s dance charts.

In 2007, Ho attempted to break into the US market by releasing her single China Wine with rapper Wyclef Jean. The music video drew extensive criticism from Christians for Ho’s scantily clad outfits, her suggestive dance moves, and the song’s lack of Christian messaging. Plans for a US album halted in 2010 as Singapore authorities began to investigate City Harvest’s use of church funds to invest in the Crossover Project.

Although Ho was never charged, Singapore’s Commissioner of Charities accused Kong of diverting funds to the project while claiming to use the money to help build a sister church in Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia. A witness testified that the church-building funds were used for promoting Ho’s music career instead. City Harvest, which had also purchased $500,000 worth of Ho’s unsold albums, said it was not illegal to use the church’s money for the Crossover Project, because it was in line with the church’s constitution.

On June 26, 2012, Singapore police arrested Kong and four church leaders and charged them in court the next day.

During that time, many congregants left City Harvest. One attendee, Andrew Koay, wrote that he had decided to leave and attend another church. “I wasn’t taught to think about the messages; instead, I felt encouraged to take everything superiors say as gospel truth because my leader is ‘God’s anointed,’” he wrote.

Meanwhile, others like Lum decided to stay. When Lum first heard the news that Kong had been arrested, he felt confused and devastated. He had heard exciting updates that the Crossover Project had led to a revival in Taiwan and that Taiwanese Christians were moving to Singapore to study at the church’s School of Theology.

“We thought we were doing something for God, and suddenly everything stopped,” he said. “Did we [do] something wrong as a church?”

Lum acknowledged that there could have been “some technicality about funding that went wrong.” But he remains convinced that the motives behind the project were pure. “We are not perfect people,” Lum said. “There are things that we are also not proud of. But God help[ed] us. God [forgave] us.”

In 2017, the Singapore High Court sentenced Kong to three-and-a-half years in jail after he appealed against his original eight-year sentence meted out in 2015. Five other church leaders also served reduced jail terms ranging from seven months to three years and two months for their roles in misusing church funds.

On August 22, 2019, Singapore authorities released Kong from prison after two years and four months for good behavior. Two days later, he went back to City Harvest Church. “I want all of you to know that I’m so sorry, so sorry for any pain, anxiety, disappointment, or grief that you have suffered because of me,” he said in a four-minute speech to church members.

“I hope to serve together with you in this house of God in the many, many years to come.”

He returned to the pulpit in August 2020.

Kong spoke candidly with Wan about his regrets about his attitudes and actions as the leader of a prominent, growing church. The “old Kong” was angry, intense, impatient, unforgiving, and excessively goal-oriented. Kong also said he had been “not so happy” in the past because of the stresses of his ministry, and feared he wouldn’t be successful.

“What’s the point of gaining a church and [losing] your soul?” Kong asked Wan.

Kong shared one instance where his temper flared. When an evangelistic crusade the church had organized in Singapore Indoor Stadium was not up to his standards, he gathered his key leaders and pastors together in a room, banged his hand on the table, and shouted at them at the top of his lungs.

In the heat of his anger, he threw a pen at a fellow pastor, an act which hurt the latter’s feelings deeply, Kong said. Kong then shared about how this action affected his relationship with his colleague.

For Juang, the fact that Kong had repented of his pride and self-righteous leadership style made the video a “better testimony” than if he had repented only for mismanaging church funds. Juang remembers feeling troubled as a high schooler when he noticed Kong speaking arrogantly from the pulpit.

“That kind of apology is something you rarely see among Chinese pastors,” Juang said.

Kong also admitted to Wan that when he and Ho were promoting the Crossover Project, he had begun to think he was a celebrity, and he thanked God for granting him a reset to that mindset.

Yet Kong also praised the project, noting that the Holy Spirit had led them to “the right door, the right people.” When Wan asked Kong if he would change his approach to the Crossover Project today, the pastor was noncommittal. “You can never please both sides,” he said. “To the church, you have become worldly. Then to the world, you are not worldly enough.”

Singaporean pastor Jenni Ho-Huan believes Kong’s recounting of the Crossover Project serves as a cautionary tale about the dangers of success—including spiritual success. Prayers about God opening or closing doors treat God like a doorman, and open doors can be temptations and distractions, she argued.

“If he had spoken more about these dimensions and how his church now operates differently, relying more on a team approach, going slower, it would be more heartening,” Ho-Huan said.

Most of the negative comments focused on the fact that Kong did not mention or recognize in the video interview that he had sinned against God with the embezzlement. Some also chastised Kong for saying he had learned to forgive while in prison; his punishment was just, they said, as he had broken Singapore’s laws.

In the interview with Wan, Kong focused on the fact that his criminal trial and conviction marked that period with “a lot of soul-searching.” He also expressed gratitude to God for that “season of hardship,” which he came to realize was “an awakening.” He listed Watchman Nee, Teresa of Ávila, and Martin Luther as figures who were influential in teaching him to slow down and surrender.

“All I can say is that I didn’t hear any confession of wrongdoing, only that the ministry was huge, the ministry was too busy, the ministry used to be too aggressive, the prison was boring, the prison was not air-conditioned in the summer,” a Christian YouTuber in Taiwan known as DK opined in a video on his channel, which garnered more than 68,000 views.

“We all know that repentance, the premise, is the most central and precious point of the Christian faith,” another popular Taiwanese Christian YouTuber, Li En, said in a video that received 91,000 views. “I can only say I don’t know [whether Kong has repented] because I don’t see him mentioning anything about that in this video like this.”

Yet others disagreed. “I can feel total transformation on [pastor] Kong from [his] conversation, and his humble, transparent, and inner peace,” one viewer said. Another wrote, “Seeing Pastor Kong Hee’s life turned over and renewed by the Lord in prison, I feel happy and grateful from the bottom of my heart.”

City Harvest church members like Theresa Tan believe that Kong and the church are “bearing much fruit in repentance,” similar to what Scripture says in Luke 3:8.

When Kong returned to the church in 2019, he shared “with great honesty about how God led him to realize he had been too concerned about success and [about how] Jesus asked him if he was enough for him,” said Tan, who was part of the church’s staff for 15 years and is now managing editor of Singaporean Christian publication Salt&Light.

Tan also sees it in how different City Harvest has become. Prior to the court case, the church closely tracked the number of church members, as it was an important sign that they were carrying out the Great Commission, Tan said. But over the past six years, the church has learned to slow down.

Numbers are no longer “a chief concern—souls being saved are. And that could be one soul at a time,” she said.

Kong’s messages from the pulpit have also shifted. His sermons in 2013 and 2014 rallied congregants to be more than conquerors in seemingly insurmountable situations or expounded on God’s grand mission for the church.

Now, Kong talks about cultivating spiritual disciplines like practicing the presence of God daily. In a 2023 message, he quoted 1 Thessalonians 4:10–11, where Paul urges believers to make it their ambition to lead a quiet life, and declared, “The more I walk with Jesus, the more I understand this: There is a beauty and glory in being quiet.”

Kong’s sermons prioritize the importance of silence and solitude, says Tan. One practice Kong encouraged congregants to do was to follow Jesus’ example of going away and praying by themselves. “It’s something that is hard for Singaporeans to really come away and be with God, right? But he models it very well for us,” Tan said.

When she worked at the church from 2008 to 2023 to run its digital publication City News, Tan went on a three-day silent retreat with other staff, which felt hard to do initially. Today, she often spends a day alone with God. “It’s something that the pastor taught us,” she said. “It really makes you grow in your relationship with the Lord.”

At the end of the day, Ho-Huan believes it is not her place to say whether Kong has repented.

“The people who should take [Kong] to account are his family and fellow leaders or even other pastors in the city who are his friends,” Ho-Huan said. She noticed some marks of repentance in Kong’s sharing, such as the relinquishing of material goods, a maturing of his personality, a turning away from his previous ways of exerting control, and his experience of peace.

Yet Kong returning to lead City Harvest Church “does create problems, not because of a criminal record but because the spiritual record is muddy,” Ho-Huan said.

Kin Yip Louie, theological studies professor at Hong Kong’s China Graduate School of Theology, agrees. In his view, although Kong is aware of what led to his fall, he should also avoid situations that present similar temptations.

“Don’t be a senior pastor; just be a teaching pastor,” Louie said. “Don’t touch any money or administration duty. Just teach the Bible.”

[Editor’s note: Tan noted in a July 8 message that Kong had stepped down from executive duties, which includes handling church finances, in 2010.]

Additional reporting by Ivan Cen