At Golden Harvest Baptist Church in Stevensville, Ontario, the Stars and Stripes still hangs alongside the Maple Leaf Flag in the auditorium.

The church is Canadian, but it has American members too. Golden Harvest Baptist is just 15 minutes east of a main border crossing, the Peace Bridge, and basically located in the suburbs of Buffalo. One couple drives from Buffalo to Canada for Sunday services. Several church members live on the Canada side but drive to the US, Monday to Friday, for work. Several families in the church include Canadians married to Americans.

That’s never really been a problem before.

“In a border community, it’s just part of your culture that you don’t see the US as adversarial,” pastor Ryan King told Christianity Today.

But now Canadians are booing the American national anthem at hockey games. People are talking about boycotting US products in the stores, and maple leaves mark everything made in Canada to encourage people to buy Canadian. There’s an undeniable surge of patriotism in the country, and people who don’t seem patriotic enough are being questioned—even Wayne Gretzky, one of Canada’s most esteemed athletes, was challenged for his seeming lack of loyalty. A lot of people in places like Stevensville are taking down their American flags.

But Golden Harvest Baptist hasn’t done that, so far. The church is trying to avoid reactionary responses to President Donald Trump’s repeated insistence that Canada should become an American state. It hopes to stay calm in the face of Trump’s threats of a trade war.

“We just want everyone to be friends,” King said.

A lot of Canadians feel betrayed by their country’s closest ally, though. And Trump’s tariffs—which could go into effect on April 2, a day Trump has dubbed “liberation day”—will likely hurt people in the church, King said.

Stuff will probably cost more at stores in the US and Canada, and some goods may not be available anymore. Car manufacturers that employ church members on both sides could be impacted. The tariffs might even drive up the cost of the Sunday school material the church buys from the US.

“It’s something everyone is watching super carefully, but it hasn’t happened yet,” King said.

Similar scenes are playing out across the country as Canadian evangelicals who have had close relationships with Christians to the south try to figure out what the sharp change of international relationship between the two countries will mean for them.

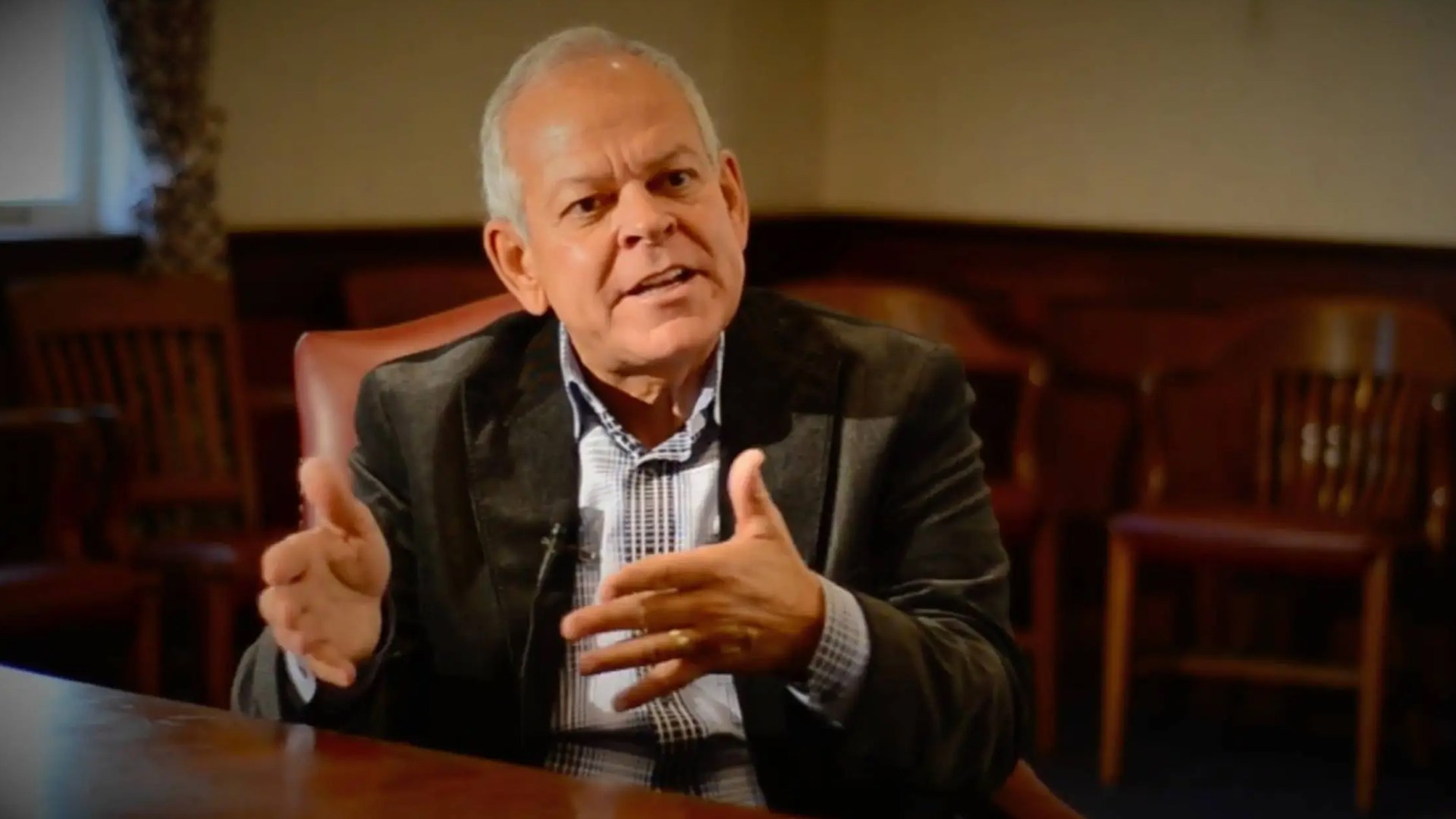

“People are a little bit bewildered,” said Brian Dijkema, a public-policy analyst who serves as president of the Canadian side of Cardus, a nonpartisan Christian think tank.

Dijkema’s denomination, the Christian Reformed Church in North America (CRC), may face particular strain, as it is in the peculiar position of being binational. Many evangelical denominations have affiliations with denominations on the other side of the border. But the CRC is a single legal entity in the US and Canada. About 25 percent of its congregations are north of the border.

Reciprocal tariffs will probably not raise costs for churches, according to Al Postma, the CRC’s Canadian executive director. Most of the materials exchanged across the border between CRCs in the US are digital and shared freely, not sold.

The leadership is concerned about the long-term consequences of a trade war, regardless.

“There’s a lot of anger and frustration and concern,” Postma told CT. “That’s true broadly within the Canadian population, and it’s reflected as well in our Canadian CRCs.”

In February, the church put out a pastoral letter recognizing the pain many Canadians felt hearing Trump and some of his supporters downplay the significance of Canada’s national sovereignty. The church lamented “the brokenness we are experiencing in our cross-border relationship.”

Postma believes the churches can continue to work together, setting aside the international politics. But Christians will have to work not to confuse the current political leadership with the nations as a whole.

Brian Stiller, a global ambassador with World Evangelical Alliance and a former president of the Evangelical Fellowship of Canada, said he thinks most Christians, north and south of the border, will connect on the individual level.

“I suspect that most of us [Canadians] who are offended by the American impulse will forgive our American friends—who generally will be more tolerant and accepting of us than their president seems to be,” he said.

But the relationship between US and Canadian evangelicals may still change. Stiller said he expects corporations, in particular, will be hesitant about depending too much on American partners or contributing to American-led projects.

“This will salt our relationship,” he told CT. “The brininess of this moment will stay in the water.”

In this tense climate, Stiller encourages Canadians to focus on words of Jesus found in Matthew 5:44: “Love your enemies and pray for those who persecute you.”

The gospel, after all, is counterintuitive, he argues.

“When your inclination is to boo their anthem, stand in respect,” he said. “When your inclination is to despise their bullying, love them instead. I see this moment not so much a test of Americanism; I see it as a test of true Canadian Christian attitudes.”

In Niagara Falls, Ontario, the pastor of Grace Gospel Church agrees. Martin Goode said people in his community and his congregation are feeling a lot of anxiety, but he’s encouraging them to see it as an opportunity to respond in Christlike ways.

“Trouble and change are normal,” Goode said. “The challenge is what kind of people we will be in the midst of it.”