Last year, Elmer—whose last name is withheld because he fears deportation—traveled alone by foot, truck, and bus from Colombia to the Mexico-Texas border. This year, Elmer spends his days in Laredo, Texas, waiting to hear how to proceed with his immigration paperwork.

Last month, President Donald Trump canceled all appointments made through the US Customs and Border Protection app and removed its scheduling feature. Next month, Elmer’s tio, tia, and primos (aunt, uncle, and cousins) in California plan to move to San Antonio, and Elmer wants to join them—but he doesn’t know what to expect.

Nor do thousands of others. Since January 20, immigrants have had to “remain in Mexico” awaiting their visa appointments. Asylum Access estimates 400,000 people with unresolved cases now remain in Mexico. The number of immigrant crossings from January 20 to 26 was 7,287, down from 176,205 in January 2024.

The change is evident in Laredo at the Holding Institute, founded by the Methodist Episcopal Church in 1880. The community center, less than a mile from the border, provides shelter, food, clothing, health services, and counseling to immigrants, regardless of status.

In 2024, more than 75,000 immigrants passed through Holding’s doors, most arriving on buses operated by Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) officers, who brought them from detention centers across Texas and from Florida and Arizona as well. Buses arrived daily, sometimes as many as four per day.

Since Trump’s inauguration on January 20, though, only a few busloads of immigrants and carloads of reporters have come. Few immigrants are getting across the border, and many already in Texas fear arrest by ICE agents.

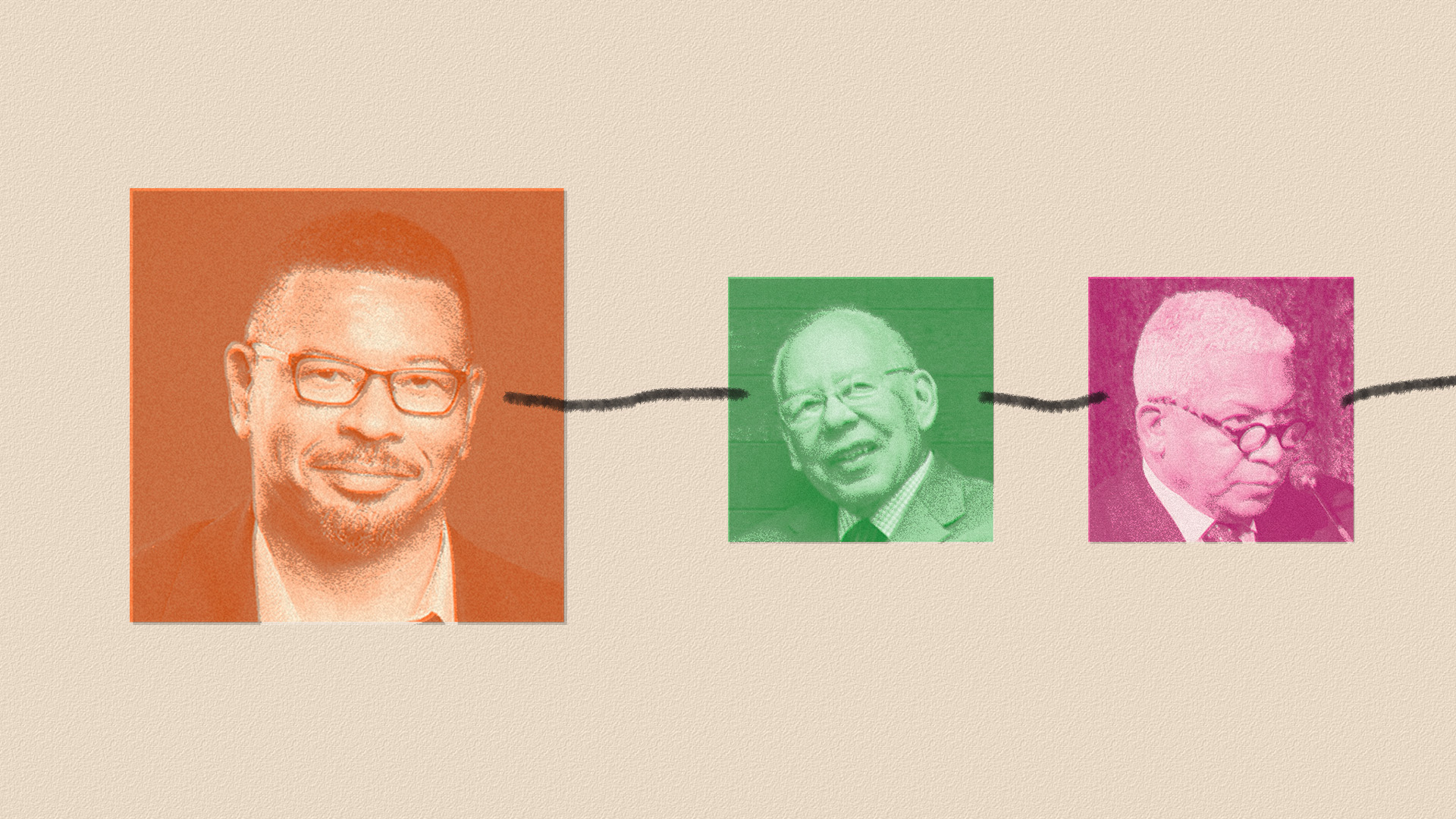

Before January 20, many families came for weekly food provisions, but three-fourths of them no longer do so. Mike Smith, a Methodist pastor who heads Holding Institute, wonders how the families are faring: “If they needed food last week, they need food this week.”

On a typical day, Elmer sits alone in the courtyard at the Holding Institute. A few other immigrants sit across the large courtyard, some chatting about their plans to join family members in other parts of the US, if they can. The center accommodates over 200 people, and each day last year the courtyard was full. Now, dozens of picnic tables and a playground are empty.

Nevertheless, a security guard still monitors the property, and a cook prepares food. Some staff members organize paperwork that stacked up last year when they struggled to keep up with demand for their services. Others prepare food and clothing for distribution to immigrants throughout Laredo.

Despite policy changes, more than 6,000 people each day cross from Laredo to Nuevo Laredo, Mexico, across the one pedestrian bridge that connects the cities—but crossers have work visas or US passports.

As the sun descends over the Rio Grande, workers leave shifts at Laredo hotels and stores. Hundreds of school children, some with birth or naturalization certificates, are also heading home: They live in Nuevo Laredo but use fake home addresses to go to school in Laredo, pursuing the better education that schools on the Texas side offer.

Pedestrians pay a dollar to cross from Laredo, pass through a scanner that beeps constantly—but stops no one—and exit to the streets of Nuevo Laredo. Crossing back to the US costs 25 cents, but the check at immigration is more involved. Officials scan passports and inquire about reasons for travel and items being carried into the US. People walk seriously and are particularly quiet on each side.

A busker, though, performs for tips: He sings and plays the guiro, a percussion instrument made from a hollowed-out gourd with a rigid surface. Kids sell candy and cigarettes to passersby.

Before Trump took office, many immigrants seeking asylum would cross this bridge as well, with visa appointments secured through the US Customs and Border Protection app (CPB One). Now, under Trump’s “remain in Mexico” order, few are able to cross. Not only the undocumented are skittish. Smith said local churches he has contacted are afraid they will lose members by helping immigrants, since the issue is so divisive.

Meanwhile, Elmer wonders about his future and relies on the services provided at Holding Institute, which now operates at half budget and in a few months may have to fire staffers. Private donations allow it to serve 100 families locally with food assistance, counseling, and medical services.

Smith struggles to obtain funding from local churches and finds that many “are concerned about immigration but not about the immigrant.”

Read part two of our border ministry series here.