This piece is the first installment in a two-part series on racial justice debates. Read the second article here.

I remember the World War II stories I was told as a middle school student. Wearing secondhand clothes and sporting an unkempt fade, I sat in a hard wooden desk too small for my growing black body in a classroom full of distracted boys and girls. The air conditioning in Alabama classrooms was unreliable, which meant sweat was an ever-present companion to our education.

The teachers told us impressionable youths that the traumas of both world wars revealed American and British grit. These great nations set aside petty concerns and turned to the needs of others. I was told at that unforgiving desk that nations and individuals discover themselves under pressure. When the fervency of belief encounters the unforgiving realities of suffering, our deepest convictions are unveiled. When cancer invades a human body and stresses a marriage, the true depth of love and commitment becomes clear.

In more recent history, COVID-19 has been a similar pressure and a similar revelation for the United States and its churches. Just as there are tests that reveal a person’s character, there are national trials that make plain what a country is.

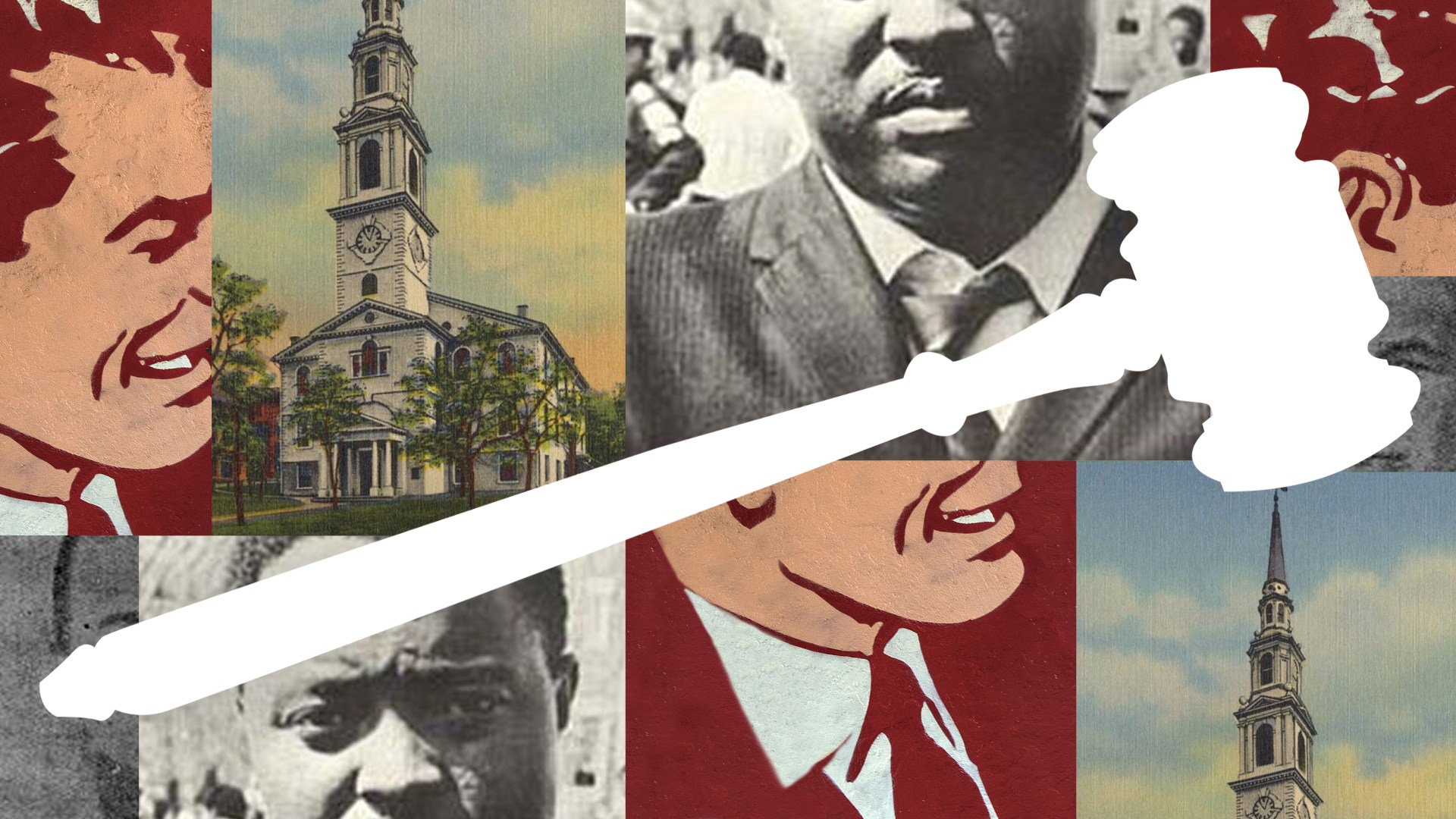

What has the COVID-19 pandemic said about the American church? Who have we revealed ourselves to be under pressure? I am talking not about the virus itself. I am talking about the social crisis of the pandemic, which brought to light the ongoing experience of racism and injustice by ethnic minorities in this country.

The church had an opportunity to lead in this area and show the world how our faith allows us to press for better treatment for all. Instead, some decided to litigate the validity of critical race theory. With Black and Asian blood drying on the concrete streets of American cities, some decided to debate the existence of systemic racism. They did not look at the thing itself. Instead, the thing itself became the occasion for a tired dispute. That debate revealed how portions of the church were ill and in need of healing well before the airborne contagion made its way to these shores.

These sick parts of the body of Christ told us to “just preach the gospel.” There are very few things more harmful for Christian cooperation than the weaponization of the gospel against Black and brown cries for justice.

Only in the context of racial injustice are we told to articulate the plan of salvation exclusively. When marriages are struggling, we don’t just preach the gospel to couples. We give them practical tools to love one another better. When parents are looking for clues on how to raise children, we do not simply preach the gospel. We give them Bible-informed tools to parent well.

As all of Paul’s letters make clear, Christian discipleship is about showing how the implications of the gospel spread out in a thousand directions. In the same way, we must show our people how the Christian faith makes a difference in how we respond to the suffering of the world. To do otherwise is a failure of discipleship.

After the lockdown began, I did not gather in a large group until I traveled to Chicago to participate in a protest. It was a hot afternoon, with the heat rebounding off the concrete and on to the masses crowding the streets of Bronzeville.

There were Black, white, Asian, and Latino bodies pressed too close together. Our understanding of the virus was still unfolding, and I was terrified I might get sick. But I went anyway because Ahmaud Arbery, Breonna Taylor, George Floyd, and their grieving families compelled me. I did not know what else to do.

I was hopeful that their deaths would force America to do what Mamie Till wanted in the wake of her son’s murder. When explaining her decision to have an open casket at her son Emmett’s funeral, she said, “Let the people see what they did to my boy.”

The last five years of deaths recorded on video have been America’s open casket, a chance to see what has been happening to Black lives.

In that context, I hoped that churches of all ethnicities would stand in solidarity with Black and brown suffering, not as a manifestation of a worldview antithetical to the gospel, as some claim, but because of what the Law, the Prophets, the Writings, and the entirety of the New Testament call for: compassion toward those who are treated unjustly. Paul calls us to “mourn with those who mourn” (Rom. 12:15).

But to mourn or weep, we must see. Instead, we turned our eyes, both as a church and as a country.

We did not have a national debate on better ways to police our citizens, nor did we consider how to address the raging mental-health crisis that often makes these violent interactions between police and African Americans so tragic.

Some thought it would be easier to label any discussion of racism as “critical race theory” or “wokism” and in so doing make that theory a threat to the republic. In other words, some found it easier to create a new Red Scare instead of tackling the ever-present problem of the color line.

For example, we watched the assault on Asian-run massage parlors in Atlanta and the endless stream of videos depicting unprovoked attacks on Asians and Asian Americans. Those videos visibly displayed the statistical rise in anti-Asian violence. Did we use that opportunity to address the racialized discussion of the COVID-19 virus? Did we finally assess the long-term damage done by common racial myths—ones that hide the poverty of some Asian populations and others that pit Asian Americans against African Americans?

No, we turned the safety of the Asian community into a debate about politically correct speech, as if we could wish away the impact of our words.

In the end, the pandemic test has made plain this truth: The church is not socially or politically ready for all that our modern, interconnected world demands of us. We need to go back to school and finally learn the lessons we have refused to learn. Our mutual hatred and distrust only makes us weaker.

When I got older and left that Alabama school behind, I realized the stories of war told there had glaring omissions or missing points of emphasis. After World War I, we rewarded Black soldiers coming back from trench warfare with a Red Summer instead of a parade. We doubled down on Jim Crow. Yes, we defeated the Nazis in World War II, but we also interned Japanese American citizens on our own soil. The test of world wars occurred not just on battlefields but in communities and cities.

Then and now, the history of this country has been an ongoing attempt to take the rubble of our repeated failures and build out of them a better place for all to lay their heads. The aftermath of the pandemic reminds how that work is more urgent than ever.

Despite our past and present failures, the church can still play a role in leading our nation toward this future, not as partisans acting as apologists for the Right or the Left but as penitents confessing our sins to one another and the world. We can admit all the ways we have failed. Why? Because we believe in a God who forgives sins.

We also believe in a God who says there is something on the other side of confession. We live in an age when politicians and political parties are loath to admit mistakes. They shift blame to the other side because they believe that vulnerability is weakness. In their minds, it’s always better to dehumanize and destroy the other side.

But we know that God won us precisely through his vulnerability, his willingness to be weak. And God’s weakness is stronger than human strength.

I am a father. I wish that meant that I always parented well, that every word spoken to my children was good, beautiful, and true. But I am human. I fail them, and the hardest thing for me to do is look my kids in the eye and say, “Dad was wrong.” But I have to so that they have permission to be wrong, permission to repent, and permission to start again. They know that our family is not made up of saints (the parents) correcting sinners (the children). Instead, their mom and dad have been given something to steward while all of us journey together in life with God.

In this racially fraught day and age, the church faces the same challenge. We can be honest about our fears and failures as a church. We can model a different way and possibly chart a different path, because the tests are not going to get any easier.

In that complex context, it’s fine for us to debate the strengths and weaknesses of theories like CRT. No theory is above reproach. But that debate cannot be used to wish away the more pressing question of justice for the oppressed. I am worried that some are losing the plain teachings of Scripture in an effort to slay the monster created in their own imaginations. It does not have to be this way.

One day, historians will tell the story of the church in this era of pandemic and racial strife. My prayer is that they find in the rubble of these years of suffering a people who bore testimony to the King who never lost sight of those most in need.

Esau McCaulley is an assistant professor of New Testament at Wheaton College and the author of Reading While Black: African American Biblical Interpretation as an Exercise in Hope.