Margaret Chege rolls out golf ball-sized pieces of dough, drizzles oil on top, and drops one ball of dough onto another.

“This is Kenyan tortilla,” she says, pressing down. “We use it to wrap sambusas.”

Sambusas are crispy, deep-fried triangular pastries stuffed with all sorts of savories—spiced beef, lamb, potatoes. Chege is here to demonstrate how to make sambusas and mandazis—pillowy, nutmeg-scented doughnuts—at the first cooking workshop of the World Relief Community Learning Kitchen. Hosted at Hillside Church in Kent, Washington, the workshop attendees on a Wednesday morning include mothers who hired babysitters, a home economics teacher, and a mother-and-son cooking team.

Chege chose these fried snacks because they remind her of home. “In Kenya, we like tea, and we eat sambusas and mandazis with tea,” she tells the class. “Anytime we see sambusas or mandazis with tea, we think, ‘Oh, now we are home.’”

As she teaches, Chege radiates confidence and pride. She came to western Washington from Kenya in 2013 with her three children. She grew up in Nairobi’s Kibera slum, the largest slum in Africa and the third largest in the world. There, as many as 50 households may share a latrine. Chege remembers how sometimes people walked carrying bags of flour, leaving a powder trail so they wouldn’t lose their way home.

Photos by Chona Kasinger

Photos by Chona KasingerShe learned how to make sambusas and mandazis as a young girl, helping her mother stuff beans in dough and sometimes beef, if they could afford it. She remembers following her mother through the streets, hawking bags of the hot food. Her mother died when she was 12 years old, and then it was just Chege and her sister selling treats to make ends meet. She was in high school when she wore her first pair of shoes.

Chege rolls out more balls of dough. Oils them. Stacks them one over another. And then she flips the whole pile onto a dry hot pan, spins it around to let the bottom toast evenly, and slowly peels off each thin layer. Now they are ready to be stuffed with ground beef and cilantro.

After all the labor of making the wrappers, Chege hands her students a tip: “Usually, I just buy Mexican tortillas from the store. I think they taste even better!”

Chege has come a long way since she and the children arrived in the United States. She was reunited with her husband, who had already been in America for years and had earned asylum, but she barely saw him; he was working 16 hours a day. Chege remembers walking to Safeway to buy a bag of flour to make sambusas—something to remind her of home—and being overwhelmed by the endless aisles of products. When she mustered up the courage to ask where she could find flour, the cashier couldn’t understand her thick accent. She returned home flustered and fatigued. She was finally in America, where she didn’t have to worry about armed groups kidnapping her son or people forcing genital circumcision on her two daughters. She felt safe here. But she also felt utterly alone, lost, and homesick.

Photo by Reva Keller

Photo by Reva Keller Photo by Reva Keller

Photo by Reva Keller Photo by Reva Keller

Photo by Reva Keller Photo by Reva Keller

Photo by Reva KellerAnd now here she is, in a brand-new commercial teaching kitchen, using her mother’s recipes and sharing childhood memories.

Standing outside the kitchen, Everett Tustin, the senior pastor of Hillside Church, peeks in one last time before retiring from the office. His heart feels full. Tustin knows Chege and her story—she and her family are members of the church. He also knows the story of World Relief kitchen coordinator Jeff Reynolds, who’s there to supervise the event. Reynolds too is a member of Hillside Church.

Tustin knows how much it took for World Relief to finally open this kitchen, years after dreaming and planning and fundraising. Tustin had also long dreamed of a church that reflects and serves the community. This kitchen—and the people who made it happen—are a manifestation of years of prayers. Now he’s proud and full of joy: This is it. Except he couldn’t have imagined it like this.

The kitchen is a 1,215-square-foot room that’s fully certified to make food to be sold to the public. Under state law that means it’s not only a teaching center, but potentially an income-generating enterprise for the community. Four student cooking stations surround an instructor station in a light-filled space where teachers and learners can mill about. A camera over the main station allows students to watch techniques up close on a TV monitor.

When he first became the pastor of Hillside Church in 2012, Tustin had a hazy vision of where he wanted to lead its ministry. At the time, the average Hillside church member was around 60 years old and white. Yet a third of the population of Kent is foreign born.

The city’s housing costs—lower than nearby Seattle—and growing diversity attracted refugees and immigrants, who saw opportunities to settle and build businesses. At Kent’s public schools, kids speak more than 80 different languages. The city has halal markets selling whole goats, Afghan bakeries offering sesame seeded barbari bread, and churches worshiping in Ukrainian and Russian.

This isn’t the Kent that Tustin once knew. He grew up in a rural farming and dairy town 20 miles away called Enumclaw, where the population of 4,000 was majority white. His world got larger after he married his wife, Rhonda. They did ministry in Chicago, and he pastored churches in Washington and Idaho for 11 years. They spent another nine years overseas, serving in Kenya, Bulgaria, and Poland as Nazarene missionaries. Then, with aging parents and two adult daughters back in the United States, Tustin accepted the senior pastor role at Hillside and the couple returned to Washington state.

Tustin had grand plans for the congregation. He wanted a more intercultural and intergenerational church. He wanted it to reflect the community’s growing diversity and serve its needs. But how to start?

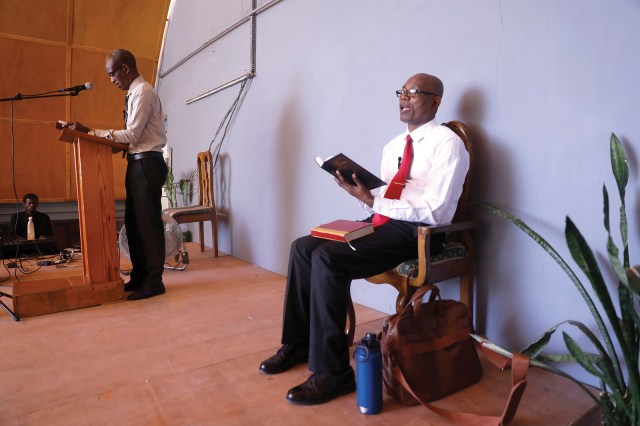

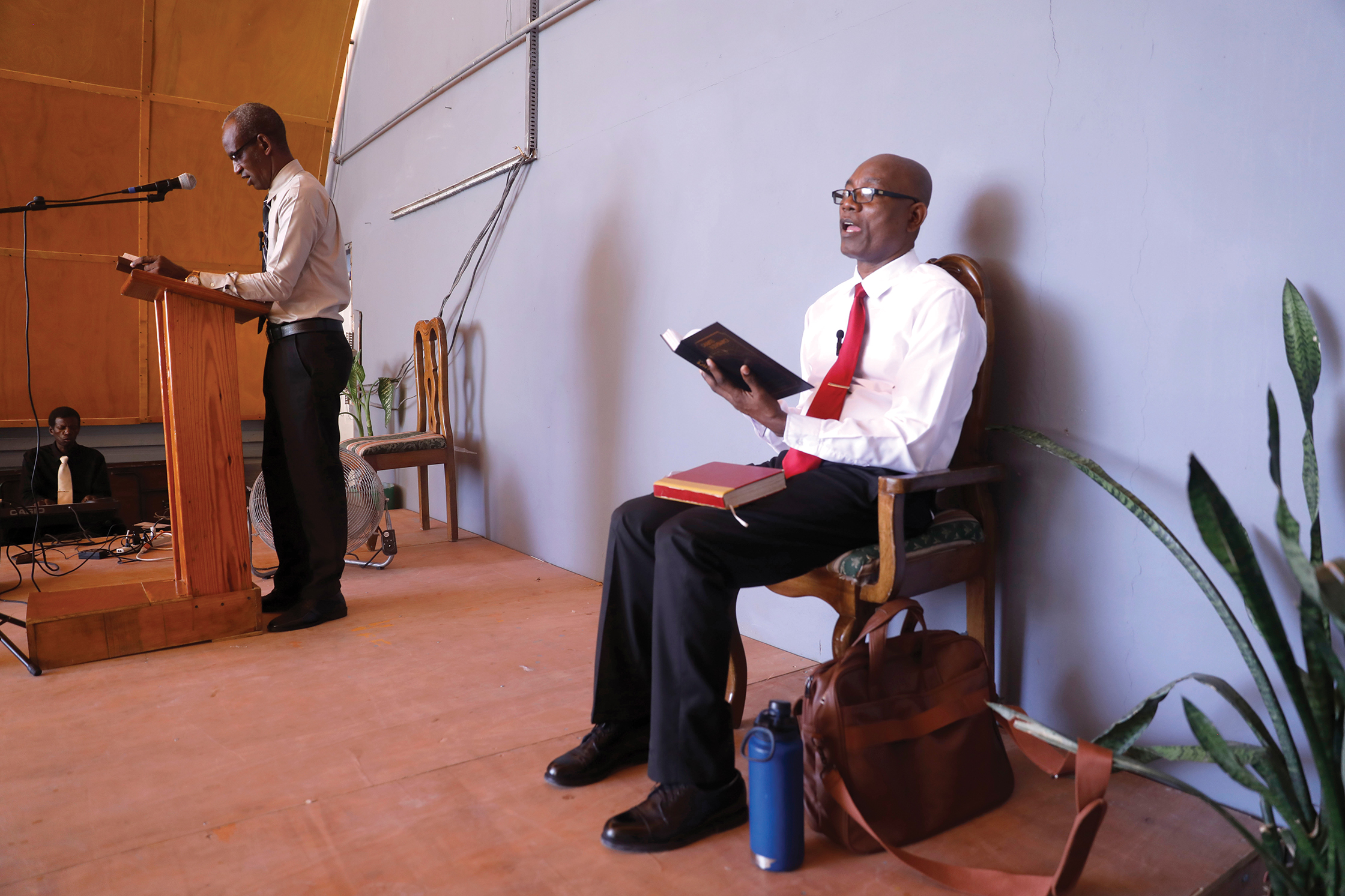

The first change Tustin made was to hire a new worship leader. He wanted people on stage to represent the community of Kent. He hired a Black man from Detroit whom he had met in Poland while he was leading choir workshops. Later, the worship leader moved back to Poland, and Tustin hired another worship leader, this time a man from Trinidad. Next, he hired an assistant pastor from Barbados, and a woman from Liberia as the children’s ministry leader. The congregation also voted in new church board members from diverse backgrounds.

Photos by Chona Kasinger

Photos by Chona KasingerThe shift in leadership led to both subtle and unsubtle changes. Worship services became more expressive—people pumped their arms and shouted, or let out tribal whistles and yodels. At times it was extemporaneous and organic, as people from African countries spontaneously asked if they could perform a duet or a song. Sometimes they sang in Swahili, Spanish, or French. Services didn’t always start or end on time. A growing number of the congregation didn’t speak fluent English or spoke with strong accents.

For some longtime church members, the changes were too much. It was uncomfortable, it was different, and it stopped feeling like home. Many left to find other churches.

It was a hard season for Tustin. He had difficult conversations with congregants who were unhappy and uncomfortable. He worried about tokenism, then worried about how to help the church not only catch his vision but lead it. It was like stretching a rubber band. How far could he pull without it snapping?

Often, Tustin wondered how the early churches did it, with all their cultural and linguistic differences between the Jews and Gentiles, the Hellenists and Romans and Hebrews.

“They just powered through,” he said. “There’s no evidence of them stopping and saying, ‘OK, let’s make this easy. Let’s make this comfortable.’ It seems like they just slammed right through it, and they broke down all those barriers.”

That first year of pastoring Hillside Church, Tustin walked to the local office of World Relief, which at the time was just down the road, and introduced himself as “the pastor of that church up the hill.” He asked if there were ways they could partner.

It was a natural move. The Christian resettlement agency provides refugees and immigrants with housing services, English language classes, employment, and immigration legal services. In those days, in the early 2010s, refugees and asylum seekers from Afghanistan, South Sudan, the Democratic Republic of Congo, and elsewhere were walking into Tustin’s church and asking for help. For baby food. For immigration advice. Tustin often directed them to World Relief.

The two ministries’ relationship began to grow. In 2016, World Relief held listening sessions with the local refugee-immigrant community, hosted at various sites including the church. They asked, What would help you thrive? What are your needs, struggles, dreams?

Attendees expressed a yearning for community. They wanted a space to connect with others, with their cultures, and with nature. Living mostly in small apartments without yards, they missed growing their own produce like they did in their home countries. They also had no safe place for their kids to roam and play.

Hillside Church is near multiple public transit lines, close to many schools and apartment complexes housing refugees and immigrants. It also had a massive parking lot that stood mostly empty and often flooded the neighboring middle school with rain runoff. So the church donated 1.5 acres of the parking lot to World Relief to develop it into a community garden.

Over several years, with funding from King County and other organizations, and with help from about 1,500 community volunteers, Hillside’s asphalt desert became Paradise Parking Plots, a community garden with 44 plots and six raised beds. It also includes rain gardens, cisterns, and flood-control bioswales, which collect rainwater before it can swamp the middle school.

Photos by Chona Kasinger

Photos by Chona KasingerAt any given time from April through September, people from 16 different countries are planting and harvesting in the Paradise plots. They pay $40 to lease a plot for the entire growing season. Two brothers from Bhutan, for example, have planted mustard greens to make the Nepalese staple gundruk, a mix of fermented and dried greens that’s pungent, tangy, and full of flavor, perfect with a bowl of rice or stewed into soup.

Another refugee, a bee farmer from Ukraine, grows wild strawberries using seeds from Ukraine, plus rows of organic tomatoes and beets to make borscht, the East European beet soup staple.

Another, a farmer from Kenya, made $1,200 in one growing season selling his tomatoes at the farmers’ market.

But the Paradise gardens are not just a place for immigrants to grow produce from their mother country. It’s a place to create friendships. They water each other’s plants, share tips on gardening in a new climate, and learn about one another’s produce and seeds.

From the start, World Relief was intentional about making this a community-supported project. Local companies have donated seeds and supplies. Neighbors have volunteered time and expertise to help maintain and improve the garden. Occasionally on Sundays, the gardeners hold a farmers’ market at the church parking lot where church members can shop and engage with them after service.

Once the gardeners had a space to grow food, they needed a space to cook it. Hillside had a small, underutilized kitchen. The church donated it and some adjoining rooms to World Relief to turn into a commercial teaching kitchen.

The project took seven years to finish. (As workers tore out walls from a church building that dated to 1968, they found lots of things that needed fixing.) In June 2023, World Relief and Hillside Church finally soft-launched the kitchen. In January 2024, they opened their first cooking workshop, where Margaret Chege demonstrated how to make mandazis and sambusas.

“This kitchen is a representation of conversations,” said Jeff Reynolds, World Relief’s kitchen coordinator, who oversees the cooking programs. The kitchen will continue to host workshops from chefs such as Chege, and it will also offer a free, three-month curriculum to help refugees and immigrants kickstart culinary careers, so that they don’t have to start out making minimum wage as dishwashers. It will also offer nutrition classes to help families navigate food deserts and American markets that are full of highly processed foods.

Photos by Chona Kasinger

Photos by Chona Kasinger Photos by Chona Kasinger

Photos by Chona Kasinger Photos by Chona Kasinger

Photos by Chona Kasinger Photos by Chona Kasinger

Photos by Chona KasingerReynolds is particularly excited about starting a preservation class dedicated to curing, pickling, and fermenting garden produce.

The project has gifted him with a new community too. He graduated from culinary school and worked in kitchens for many years, then in alcoholic beverage sales until he was furloughed in 2021 during the pandemic. That was when he and his wife started attending Hillside Church. A relatively new believer, Reynolds told his pastor, “I don’t know how my knife skills can bring people to Jesus.” Tustin told him about the kitchen project and introduced him to World Relief. And now here he was, teaching people from around the world how to properly dice onions without slicing off their fingers.

Sometimes there are language barriers and cultural misunderstandings. But that’s part of the ministry, Reynolds said. “You have to insert yourself into the uncomfortable. There’s no other way to do it. And as uncomfortable as that is, at the end, man! It changes your life.”

Chege, too, had to push through discomfort. She and her family visited Hillside in 2014 after her oldest daughter, who was attending the church’s youth afterschool program, kept begging her parents to check it out. That first Sunday, they sat at the back. After the service, Chege’s husband went up to greet Tustin, and Tustin greeted him with the few Swahili phrases he remembered from his two years in Kenya: “Habari yako? Karibu. Jina langu ni Ev.” “Hello, how are you? Welcome. My name is Ev.”

“I was like, wow. It’s my first time hearing white people speak Swahili,” Chege recalls. Immediately she felt a little more at home.

Tustin invited them to an after-service church picnic at a local park. When they arrived, Chege’s husband told her, “This is amazing. This is the exact park where I used to do daily prayer walks, asking God to find a way for you and the children to join me in America!”

They became regular attenders at Hillside. It was awkward at the start for Chege. She would leave for home almost immediately after the service. She was frustrated when people kept asking her to repeat herself or looked at her blankly because they couldn’t understand her accent. “So I think, ‘I’m just not supposed to talk,’” Chege recalled. “That was a big challenge for me.”

Tustin and his wife kept encouraging her. Your English is good, they told her. At their urging she hosted a small group at her home, where she served chapati or mandazi and tea, or, if she had time, sambusas and tea. People from other East African countries came to the group. Sometimes they worshiped in Swahili.

Chege eventually grew more confident interacting with English-speaking church members. “I gained understanding,” she said. “It’s not their fault they cannot hear my language because we have a language barrier. I became more patient in listening more and trying to explain in different ways.”

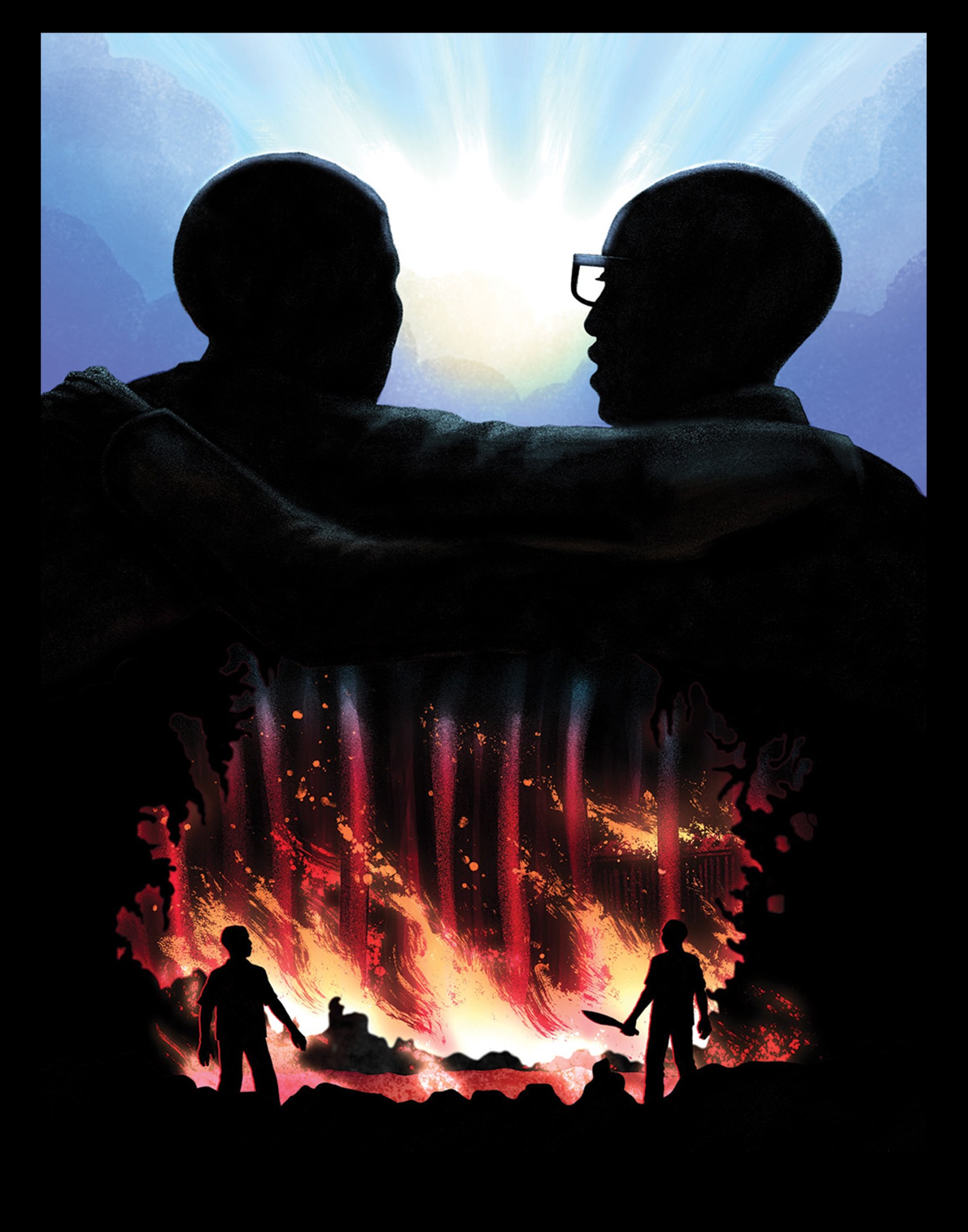

There’s a painting hanging in the church sanctuary. It’s called The Table. It features a large, wooden table in the shape of a cross, with Jesus in a white robe sitting at the head, and people of various skin shades dining before him.

Tustin’s wife Rhonda painted that picture during the pandemic years—when the nation was upside down with civil unrest and racial tension—and she had her church family in mind. It’s a vision of reconciliation, of holy communion at the feet of Jesus, of a table where family members can feel so safe that they will freely voice their thoughts, disagree and forgive, compromise and celebrate.

It’s the vision that Tustin had for his church 12 years ago when he moved to Kent. The reality is not as beautiful or peaceful as the painting. The reality is messy, hard, and frustrating, and oftentimes disappointing.

Photos by Chona Kasinger

Photos by Chona KasingerTustin turns 62 this year. He doesn’t know how many years he has left as the senior pastor of this church, and he likes to quote an Indian proverb: “Blessed is he who plants trees under whose shade he will never sit.”

He still has yearnings for his church that have not come to fruition. But, Tustin said, “I feel like the vision of the things we’re trying to do is bigger than my lifetime.”

What he is already seeing, however, sometimes brings tears to his eyes: listening to the kitchen workshop, seeing Chege and Reynolds lead, bumping into the Afghan women who gather for sewing classes in the church basement three days a week, watching church members from all walks of life pray over one another.

Each moment reminds him: It’s not his table. It’s the table Christ built, when he bore all sin and brokenness on the Cross and invited the whole world to join his family. It’s the table he set when he said, in the Gospel of Mark, “Whoever does God’s will is my brother and sister and mother.” ′

Sophia Lee is global staff writer at Christianity Today. She lives with her family in Los Angeles.