I felt a growing knot of dread and distrust in my belly.

Beside me, my friend, our church’s associate pastor, spoke low into her cellphone as our taxi whizzed past Seoul’s Han River. Swift waters flowed between green manicured banks. On the other end of the line, I overheard an angry voice describing the latest allegations of sin by our head pastor.

As I eavesdropped, I didn’t know about the cascade of upheaval that would lie ahead: We were a few months away from a violent church split, a formal investigation into bullying allegations, and a precious young woman’s death.

My story of church hurt has clues but not necessarily answers. I’m not sure I’ve learned whatever I was supposed to. Grief plants deep roots and bears strange fruit. This is a story for the ordinary people in other churches where investigations are unfolding—people who are wondering what really happened, whom to believe, and how to proceed with love.

The most prominent stories of spiritual abuse center around leaders of big ministries, so we might assume that it’s those environments that foster unhealthy power dynamics. But my gathering was small, sometimes just 40 people on a Sunday or up to 100 during busy weeks.

We were a motley crew of mostly expatriates. For three years we shared meals, held each other’s babies, mourned each other’s losses, and worshiped joyfully together.

How did we fall apart so fast?

In a church this close, conflict divides families down the middle. In our case, there was no embezzlement, affair, or heresy; there were allegations that our head pastor was abusing his power—and was seizing more.

Two factions formed. People believed either the associate pastor or the head pastor. I had dear friends in both groups. When you trust people saying opposite things, it feels at once emotionally impossible and morally imperative to pick a side. I wondered, Whose story should I believe? What if I make the wrong choice?

Lying awake scrolling text threads or replaying conversations in my head, I worried whether I’d said the right thing. I felt enormous pressure to walk perfectly through a broken situation.

At the same time, I gained a strange comfort from knowing that God was not surprised by our kinds of brokenness. The New Testament shows religious leaders gunning for power, such as Pharisees aligning with the Roman government, Jesus’ disciples jockeying for position, and early church leaders being warned of domineering over their flocks in the Epistles.

God’s image of leadership, however, does not look like the oppressor’s whip or the boss’s prime parking spot. It looks like the shepherd feeding his flock (1 Pet. 5:2). It looks like Jesus wrapping a servant’s towel around his waist as he kneels to wash his followers’ feet (John 13:4–5). So why do abuses of authority keep happening in ministry?

Some evidence suggests that leadership draws narcissists, and by putting priests and pastors on pedestals, we can value, in the words of professor and therapist Chuck DeGroat, “external competencies over Christian character.”

Leaders need brothers and sisters around them with the integrity and relational credit to say, “Love you, buddy. Now cut it out,” instead of being yes men. Pastoral bullying occurs within systems designed not only to protect unhealthy leadership but also to promote it.

Our head pastor wasn’t a celebrity or even a leader with swagger. He came in early to clean toilets. But he could speak without thinking. He could act impulsively. He was generous, but he could also make unilateral decisions. Our associate pastor was equally complex. She could be warm with me while badmouthing others. She affirmed people’s gifts. She could be a fierce advocate. In my view, she could also be manipulative.

Lots of things can be true at once.

Our church had also recently grown, ironically, from an influx of members from a nearby church decimated by spiritual abuse. Historically, organizations are most vulnerable to conflict in times of change. As we grew, our organizational systems didn’t keep up. Volunteers saw their ministries replaced by paid staff. People felt displaced and devalued, with no formal mechanism to field complaints.

Things came to a head. Our associate pastor, our intern, and about half my friends were no longer speaking with our head pastor. They accused him of misogyny, lying, bullying, and even abandoning the faith. They said it was exactly like Mars Hill. The gloves were off.

Our parent church sent in an investigatory committee, which was hardly viewed as a neutral third party. Other classic mistakes were made: We heard the usual exhortations to submit to authority and to stop gossiping.

All this took place during the COVID-19 pandemic, and the isolation that came with it exacerbated the situation. In 2020, South Korea’s regulations forbade social gatherings or eating together. Misunderstandings that might have been cleared up over a bowl of bibimbap instead festered for months.

Long-stewing silence turned into open letters, reply-all emails, and vicious accusations: The associate pastor was campaigning for power; the intern was playing the victim; the head pastor was a sexist tyrant.

Open battle now raged around us. Friends left the church every week. Some switched to a new one. Many, though, left organized Christianity altogether, thoroughly disillusioned.

Helpless, I asked God what I could do. My sense of responsibility was sometimes invigorating but sometimes overwhelming. With an earnest desire to be useful, I forgot at times that God— not me—held our body, that the Spirit loves the bride infinitely more than I and fights for her more powerfully than I could.

I searched the Scriptures for wisdom. Paul’s letter to the house churches of Rome served as a foundational text for me. In Romans 12, two factions are glaring at each other over a chasm of differences. The believers had fractured over status, ethnicity, religious habits, and biblical interpretation. Without sacrificing doctrine, Paul entreats them, exhorts them, and invites them—using every way he knows how—to return to siblinghood.

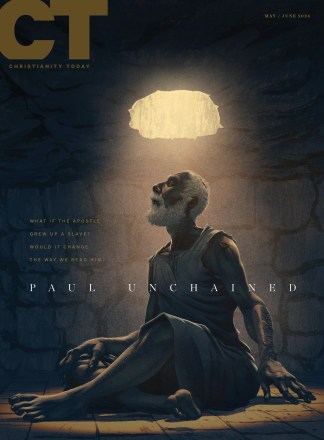

Illustration by Keith Negley

Illustration by Keith NegleyI asked God to give me Paul’s same affectionate tone and unflinching honesty in every interaction.

I felt like I couldn’t process things with my pastors or church friends. Everyone I was close to was involved in either the investigation or its fallout. It felt like my leaders were in triage mode, zeroed in on only the people most central to the conflict. I turned to existing books, articles, and podcasts around religious bullying, but all seemed to assume the worst, written in stark black and white. Nothing reflected the gray I found myself navigating.

Desperate for clarity, I was relieved to find an affordable Zoom therapist—someone I could finally talk to without a filter. Music helped too. I often led our church through singing “Prophesy Your Promise”:

When I only see in part

I will prophesy your promise …

’Cause you finish what you start

I will trust you in the process.

What a comfort to sing out to a God who is good “in the middle of my mess.”

After interviewing everyone involved and reading through hundreds of emails, the investigation committee found our head pastor not guilty of spiritual abuse.

But, they told the church, he had acted immaturely and had failed to show a shepherd’s heart. He had demonstrated negligence in handling the intern’s contract, allowing bad feelings to linger without resolution. They mandated therapy for him, set up an elder board, and provided paid time off for him and those bringing charges.

The schism remained. Our intern, children’s pastor, and eventually associate pastor resigned. Other folks trickled out—some to protest injustice, some just weary of the whole ordeal. Those of us who stayed felt called to rebuild something healthier, determined to see some sort of redemption. Things seemed to be settling.

Then came the phone call.

“Jeannie,” said my best friend from church, pausing to control her ragged breath. “Our intern has been killed.” Late the night before, our estranged friend and former intern was walking across a street when a drunk driver ran the red light and hit her. Our sister was gone.

The woman was so young, only beginning ministry; she was deeply beloved, yet as a foreigner deeply alone in a country not her own. She had hotly debated policies, prayed earnestly for discernment, fought passionately for what she felt was owed, and at last left the community she’d loved.

And now she was gone. It seems unfathomable to me that this was how her earthly story ended.

I wish I could say our community united around our grief. But if you have been plunged into communal tragedy, you know how disparately each member experiences it. Our friend’s death did not draw us together. It was our final shattering. The church fully split, with a violence that still astounds me.

Change dawns slowly. Before moving back to America, I saw some glimmers of hope. Our head pastor, chastened, confessed and apologized from the pulpit: “I made this church’s success my identity, and I’m sorry.”

The nascent elder board (which my husband was on) formed a constitution with provisions for firing a pastor. My husband and I preached on Romans 12 the Sunday we said goodbye. After months of silence, a friend and I shared a face-to-face coffee and the first tearful hints of reconciliation.

I never saw a full resurrection. The baggage feels like a permanent part of my church story now. I’m hyper-attentive to posturing, signs of staff resentment, leaders on pedestals, and communication that feels slick or insincere.

Trust is going to take time. Tentatively settled into a new Christian community here in America, I can sense myself holding people at arm’s length. For the first time since I was a teenager, I’m not leading worship or a small group.

For now, showing up is hard enough.

I still wonder if I walked well. Was I supposed to pick one side of the river or the other? Or was floundering around between them the only way?

As Beth Moore says in her memoir, “All my knotted-up life I’ve longed for the sanity and simplicity of knowing who’s good and who’s bad … God has remained aloof on this uncomplicated request.” I’m a mixed bag myself, a little bit victim, a little bit villain, though I trust the Holy Spirit is working on the ratio.

There were no evil oppressors or flawless victims in our story. We need to stop demanding that there be. There must be a better way to foster a culture of harmony and righteousness.

Authors Scot McKnight and Laura Barringer describe how to develop “circles of tov,” or goodness, by establishing norms of service, grace, courage, and truth in whatever spheres we influence. For most of us, this is the way forward through a season of church investigation or hurt.

Instead of closing ranks or annihilating anyone involved, we lament. We pray. Earnestly seeking the Spirit, the Scriptures, and wise counsel, we recognize we’re also going to make mistakes. We deal gently with one another, even under duress.

With an eye for common red flags and the tender affection of siblings, we ask leaders hard questions. We invite experts in. We remain in the waters of ambiguity longer than is comfortable.

Any church investigation is a call to repentance, both personal and institutional. When it comes, may God grant us servant leaders, systems of accountability, and habits of humility. May we stumble forward toward justice and genuine peace.

Jeannie Whitlock is a writer based in the Chicago suburbs.