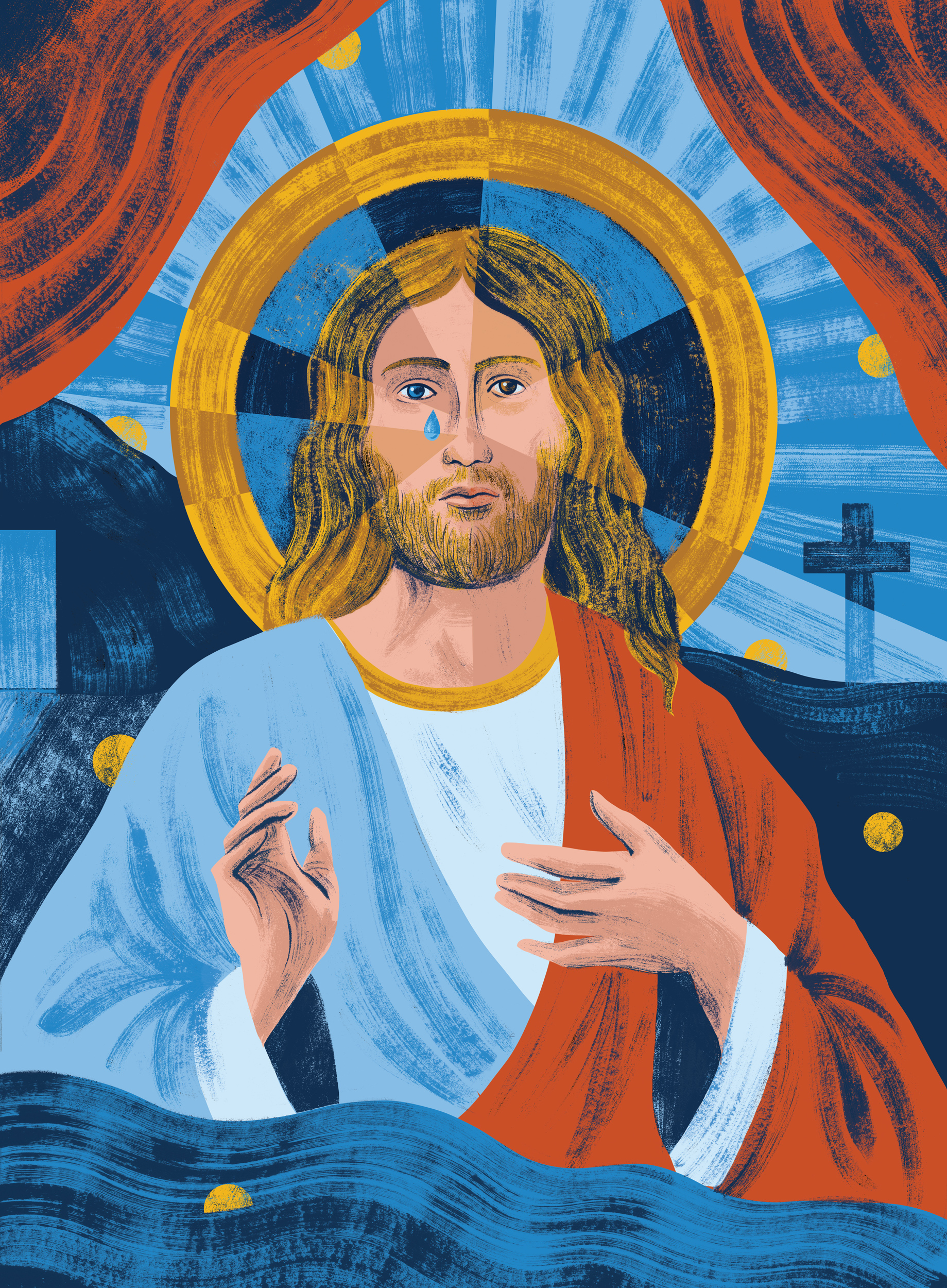

Not long ago, I came across several portraits of Christ that someone had posted online. Using the image on the Shroud of Turin as a basis and employing artificial intelligence, the pictures speculated what Jesus might have looked like before his crucifixion.

I viewed the images with interest, wondering if they would produce a sense of recognition in me as someone who is in Christ. But I can’t say my heart was moved in any particular way about them.

I certainly did not feel the way I usually do when someone I care about deeply comes into view. I could not say, “Oh, that’s Jesus! I would know him anywhere!”

No figure is as familiar to us as Jesus Christ. At the same time, no figure is as unfamiliar.

I first began to read about Jesus over 50 years ago as I worked the midnight shift at a fast-food restaurant. Having recently graduated from high school, I was trying to decide what direction my life should take. I thought it would be good to have a spiritual dimension and had been exploring Eastern mysticism and the occult, though not very seriously.

One day, it dawned on me that the Bible was a spiritual book. So during my breaks at the restaurant, I started reading the New Testament.

It didn’t take long before Jesus Christ—not so much his message as his personality—captured my attention. Or maybe I should say what attracted me was the mystery of his personality.

What kind of person is so compelling that someone would give up career or family to follow him? I’d read in the Gospels how Peter walked away from the security of his fishing nets and Matthew abandoned the lucrative returns of the tax table. Although the Jesus I encountered in the Gospels was not entirely new to me, he was strange.

I have been reading about Jesus ever since, and he still puzzles me. Although I have been a pastor and a Bible college professor, there are times when I wonder if I know Jesus at all. I don’t mean that I question whether I am truly a Christian or whether he is my Savior.

But often, when I read the Gospels, the Jesus I find is not what I expected. He will speak or act in ways that disturb me. Sometimes, like the disciples, I am irritated and want to ask Jesus, “What were you thinking?” Other times I am struck with wonder and want to say, “What kind of man is this?”

In ordinary relationships, we tend to keenly observe the kinds of details Scripture withholds about Jesus. Not only do we note face and form, but we pay attention to all the little details that contribute to personality: the glint in someone’s eye, the curve of a crooked smile, the jokes that make them laugh.

Personality is the word we use most often to speak of such attributes. It isn’t simply a synonym for individuality but is a description of the distinctive ways a person expresses that individuality. Personality is the blend of characteristics that identifies the individual as an individual.

The Bible has little to say about such details where Christ is concerned. The information it does provide is relatively sparse; it’s scattered throughout the four Gospels in a piecemeal fashion or can only be guessed. The apostle John could speak of what he had heard with his own ears, seen with his own eyes, and touched, but we cannot (1 John 1:1). We depend on what is written.

Consequently, if we are to know Christ on a personal level, that intimacy must come in a way that differs from most of our other relationships. At the same time, Jesus promised a special blessing to those who have not seen him yet have believed (John 20:29).

God has provided us with two primary vehicles to mediate this knowledge of Christ to us.

The first is what has been recorded about him in the Scriptures. The other is the inner testimony of the Holy Spirit, who is also called “the Spirit of Christ” (Rom. 8:9).

In 2 Corinthians 4:6, the apostle Paul observes: “For God, who said, ‘Let light shine out of darkness,’ made his light shine in our hearts to give us the light of the knowledge of God’s glory displayed in the face of Christ.” This is a curious thing to say to those who have never seen the face of Jesus.

Apparently, despite the Bible’s lack of any detailed description of the appearance or personality of Jesus, we know more than we think.

There is a light that shines in our hearts that reveals the unseen face of Christ. Not in a literal sense. But by the Spirit, we come to know Jesus personally and intimately. He, in turn, displays the glory of the invisible God to us through his humanity.

Theologians have much to say about the personhood of God, especially in connection with the church’s doctrine of the Trinity. They have had less to say about God’s personality. One reason for this reluctance may be a concern not to anthropomorphize God. The Scriptures repeatedly assert that God is not a man (Num. 23:19; Job 9:32; Hos. 11:9).

Theologian Helmut Thielicke warns in The Evangelical Faith that making the human person a model of God is a mistake:

Any equation of God and person, or any attempt to make the human person a model in thinking of God, is thus ruled out from the very outset. … Equations of this kind would again make God an image of the creaturely in the sense of human religion or idolatry.

Yet what analog could be more anthropomorphic than the one God chose for himself? According to Genesis 1:26–27,

Then God said, “Let us make mankind in our image, in our likeness, so that they may rule over the fish in the sea and the birds in the sky, over the livestock and all the wild animals, and over all the creatures that move along the ground.” So God created mankind in his own image, in the image of God he created them; male and female he created them.

It is hard to see how one could have a personal relationship with God as he presents himself in these verses without some correspondence between God’s nature and what we think of as personality. Even if it can be proved that the notion of personality is not relevant in this context, it cannot be meaningless where Jesus Christ is concerned. Hebrews 2:17 states that Jesus was made like us in the Incarnation, “fully human in every way.”

Jesus was not an empty shell into which the divine nature was poured. He was not merely wearing a fleshly body. Although he existed as a divine person prior to the Incarnation, when he became flesh, the Logos took on a new dimension (John 1:1, 14). Jesus did not cease to be what he was before but added human nature to his person. In doing so, both natures retained their fullness.

Jesus is not two persons, one human and the other divine, who cohabit in the same flesh. He is the one person of Christ who is both truly human and truly divine in every sense. As such, he possesses a personality. One reason Jesus became human was in order to provide an “exact representation” of God’s being (Heb. 1:3). The humanity of Jesus tells us what God is like.

“Personality,” wrote Francis Rogers in 1921, is “the incarnation of individuality.” When we talk about someone’s personality, we are usually speaking of the impression they leave us with. Are they friendly or unfriendly? Do they have a sense of humor, or are they serious? Are they shy or outgoing? Personality inventories tend to describe these traits in polarities. Introversion is the opposite of extroversion. A person focuses on either tasks or relationships. They are a leader or a follower. In reality, these qualities exist on a continuum.

Personality is a description of our ways of acting and relating to others. It includes temperament, habits of behavior, values, and preferences. Character is also expressed through personality but is not necessarily identical to it.

Graces like the fruit of the Spirit (Gal. 5:22–23) that shape a Christian’s character may be the same for all believers, but we do not all express those qualities in the same way.

The Gospels reveal relatively little of what typically interests us about people when they speak of Jesus’ personality.

We know nothing exact about the Savior’s physical appearance and next to nothing about the sound of his voice. We know that he was a builder but not what he did in his spare time other than pray, go to dinners, weddings, and take at least one nap. How did he act when he was among friends? We know that Jesus cried but do not know what made him laugh.

There are occasional moments in the Gospels, though, when the clouds of silence part and the rays of Jesus’ personality peek through.

The religious leaders set a trap for Jesus by waiting for him to heal on the Sabbath, and he gazes at them angrily, “deeply distressed at their stubborn hearts” (Mark 3:5).

A misguided youth believes he is already good enough to inherit eternal life and asks what else he must do, and Jesus looks at him with love (Mark 10:21).

Jesus touches a leper and speaks tenderly to a shy woman (Luke 5:13; 8:48). Jesus weeps, comforts, rebukes, and threatens. The God revealed to us through the humanity of Christ is someone who not only thunders but also sobs and sighs.

Personality is our point of connection with other human beings. We know them as individuals through their personalities. We bond with people who have personalities similar to ours. Just as often, we take note of our differences. Identity is not only a matter of knowing who we are; it is also a function of knowing who we are not.

In the face of the Gospels’ scant detail about Jesus’ personality, we can be tempted to model him after ourselves.

In a 2010 essay in Christianity Today about the failure of historians to reconstruct a “historical Jesus,” Scot McKnight described how he gave students a standardized psychological test divided into two parts. On the first part, the students described Jesus’ personality. On the second, they described and compared their own. “The test is not about right or wrong answers, nor is it designed to help students understand Jesus,” McKnight explained.

Instead, the test revealed that people tend to think Jesus is like them. Introverts think Jesus is introverted, for example. Extroverts think the opposite.

“If the test were given to a random sample of adults,” McKnight wrote, “the results would be measurably similar. To one degree or another, we all conform Jesus to our own image.”

Our mental image of Jesus is often shaped as much by cultural assumptions and personal experiences as by Scripture. This is why the Jesus in our mind often feels so familiar and comfortable. We believe that he looks like us. That he shares our tastes and reflects our expectations. That the truths he espouses are those of which we are already convinced. That the Christian life Jesus demands looks like the one we are already living. Republican Jesus, woke Jesus, rugged manly Jesus, gentle Jesus, mythical archetype Jesus—they are all, to some degree, self-curated versions of the biblical Jesus.

At best, they may emphasize certain features that we see in the Gospels’ portrayal of him. But mostly, they are images that resonate with values that we already hold. At worst, they are idols we have fashioned in our own image.

We do not need a photograph to see God’s glory displayed in the face of Christ, but we do need the Word and the Spirit. Christ’s revelation of the Father is made known each time we read about Jesus’ words and actions in Scripture. God’s Spirit uses that Word to shine in our hearts and disclose both the Father and the Son to us. As Jesus reveals the Father to us, the Spirit makes Christ known.

This understanding, which is gained by the Word and applied by the Spirit in conjunction with our experiences, provides us with a clearer sense of who Jesus is than any picture could, because it provides a personal knowledge of Christ that works from the inside out.

There is more to this knowledge than a set of traits—from which we would doubtless draw the wrong conclusions. Much of our interest in the personality of Jesus does not spring from a desire to understand Jesus better but from a desire to show that Jesus thinks and acts like us. Instead, the understanding the Spirit provides moves in the other direction.

The knowledge of Jesus that we actually have goes beyond the list of likes and dislikes or awareness of the sort of quirks we usually attribute to personality. For the believer, knowing Jesus involves the incorporation of Christ himself into our way of thinking and acting.

In other words, we come to know Jesus personally not only by reading about him but by becoming like him. There are two important features of this experience. One is that it is progressive. This transformation does not happen instantly when we are born again. It is ongoing and only brought to perfection in eternity.

The other is that this experience is integrated with the uniqueness of our distinctive personalities. As we become more and more like Christ, the distinctiveness is not wiped away. Instead, Christ displays himself through the various personality styles of those who belong to him.

If personality truly is the incarnation of individuality, you would think we would know our personality better than anyone else. It is, after all, who we are. Yet the popularity of tests and inventories that promise to summarize our personality traits for us seems to suggest otherwise. Perhaps it is easier to be aware of what others are like than ourselves. Or maybe we take these tests hoping to confirm what we already know about ourselves, to identify with our particular social tribe.

However, while personality inventories and surveys can be a valuable way of synthesizing data about people, they can also be too reductionistic to tell the whole story. Instead of highlighting the unique ways Christ works through each individual, they may slot individuals into categories that are often too broad or vague to be helpful.

What is more, they do not do justice to the mysterious way God works through the unlikely to accomplish his goals. God often works despite our personalities as much as he works through them.

In a sermon on the white stone and new name of Revelation 2:17, George MacDonald describes each person as having an individual and unique relationship with God. “He is to God a peculiar being, made after his own fashion, and that of no one else,” he said.

For MacDonald, this meant that each person is blessed with a distinctive angle of vision when it comes to understanding God:

Hence he can worship God as no man else can worship him—can understand God as no man else can understand him. This or that man may understand God more, may understand God better than he, but no other man can understand God as he understands him.

As truth is worked out in our daily experience, we not only learn about Jesus; we put him on display in a way that is just as unique as the insight that MacDonald describes. In MacDonald’s words, each one of us is “to God a peculiar being, made after his own fashion, and that of no one else.” We may share some traits with others, but nobody else is exactly like us. This experiential knowledge of Christ mediated through our experience is also refracted through our distinctive personalities, the way light shines through stained glass.

Perhaps the students who completed the psychological profile on Jesus in McKnight’s class were on to something after all—not in thinking that Jesus was like them, but the other way around.

As the poet Gerard Manley Hopkins says in “As Kingfishers Catch Fire,”

Christ plays in ten thousand places,

Lovely in limbs, and lovely in eyes not his

To the Father through the features of men’s faces.

Those who know Christ by experience serve as a medium through which others see Jesus. Their lives are the stage upon which he plays, and his beauty is revealed through them. More than the beauty of a single personality profile, this is an image with untold variety. And while Jesus is a human being with a real personality, he is also the God who has chosen to reveal himself through those he has created and saved.

As we are “being transformed into his image with ever-increasing glory” (2 Cor. 3:18), Jesus shows himself as, riffing on Joseph Campbell’s theory of heroes, the Savior with 1,000 faces. We put Jesus on display the way a diamond reveals its glory: in countless facets.

John Koessler is a writer, podcaster, and retired faculty emeritus of Moody Bible Institute. His latest book is When God Is Silent, published by Lexham Press.