Before my retirement in 2021, I traveled regularly to speak at Christian conferences in America and East Asia. These preaching engagements often occurred during the Mid-Autumn Festival, which is a popular time for Chinese churches—whether in the US or in Taiwan, Hong Kong, China, and the Philippines—to hold special events. While I deeply enjoyed fellowshipping with these brothers and sisters in Christ, a part of me missed my family, especially when I found myself gazing at the beautiful full moon in the sky.

My fascination with the moon began in my youth. As a 14-year-old in Taiwan, I watched footage of Neil Armstrong stepping onto the moon on a neighbor’s black-and-white TV. In that awe-inspiring moment, a secret dream to work at NASA was birthed within me, even though it seemed impossible at the time.

In 1987, God fulfilled my dream of working at NASA, where I eventually became a research and development (R&D) lab director. I’ve long regarded humanity’s explorations of the moon not only as a scientific endeavor, but also as an exercise in trusting God, who has a remarkable way of weaving together our dreams and his plans for us into a tapestry more beautiful than we could ever imagine.

Over the moon

During the Mid-Autumn Festival, or Moon Festival, as it is known in the West, the moon is at its roundest and brightest, the autumn air is cool and dry, and Chinese families enjoy a time of reunion. The event, which falls on September 29 this year, occurs on the 15th day of the eighth month of the lunar calendar.

Many Chinese Christians observe the festival as a cultural celebration, resonating with its themes of familial bonding and gratitude. This emphasis is reminiscent of US and Canadian Thanksgiving celebrations, where families gather to give thanks and share a meal together.

Besides traditions like eating mooncakes, Chinese people may also recite poems that extol the beauty of the moon with a tinge of melancholia. A popular choice is renowned Song Dynasty poet Su Shi’s “Song of the Water: Mid-Autumn Festival”:

When does the bright moon appear?

I raise my wine to ask the azure sky.

I cannot guess what celestial palace reigns,

What year is it tonight up high? …

In life, there’s joy and sorrow, parting and reunion;

The moon may wax or wane, perfect or crescent;

Such is the way of the world, hard to comprehend;

Yet may we all endure, till the end of our days;

Sharing the beauty of the moon, though miles apart.

Bittersweet poetry like Su Shi’s often captures the essence of the season. But one tale stands out for its poignant depth: the legend of moon goddess Chang’e.

According to this Chinese myth, Chang’e was driven by a yearning for eternal longevity and stole an elixir of life from her husband, Houyi, who had received it from the Jade Emperor as a gift after shooting down nine suns that were burning up the earth. Upon consuming the potion, however, Chang’e found herself ascending to the moon, never to return to earth again. There she remains in eternal solitude, and this story now serves as a reminder of the loneliness that can accompany the quest for immortality.

The flight of Chang’e to the moon may be a fable, but going to the moon is a desire that Christians throughout the centuries also share—and a feat that was accomplished merely 50 years ago.

More than a moonshot

In our decades-long pursuit of lunar expeditions, one thing that has encouraged me is that many of the astronauts and scientists involved in the American space program were devout Christians. The vastness of the universe they encountered led them to appreciate the magnificence of our Creator.

On July 20, 1969, Neil Armstrong and Buzz Aldrin landed the lunar module of America’s Apollo 11 in the Sea of Tranquility on the moon. The next day, Armstrong stepped onto the surface of the moon and said the famous line, “One small step for man, one giant leap for mankind.” Aldrin followed 20 minutes later.

Before the two astronauts stepped out onto the lunar surface, however, Aldrin, who was an elder at Webster Presbyterian Church and had arranged with his pastor to take Communion in the module, remembered Jesus Christ on the moon. He also read two handwritten passages from the Bible, John 15:5 and Psalm 8:3–4: “I am the vine, you are the branches. Whoever remains in me, and I in him, will bear much fruit; for you can do nothing without me” and “When I consider thy heavens, the works of thy fingers, the moon and the stars, which thou has ordained; what is man, that thou art mindful of him? And the son of man, that thou visitest him?”

A year prior, humans had entered lunar orbit and circled the moon for the first time through the Apollo 8 mission. On Christmas Eve in 1968, astronauts Frank Borman, Jim Lovell, and William Anders made a live television broadcast from the moon’s orbit to Earth and individually recited Genesis 1:1–10. This broadcast won an Emmy award for the highest viewership worldwide at the time.

Later, James Irwin became the eighth man to walk on the moon as part of the Apollo 15 moon-landing mission in 1971. During his mission, Irwin experienced an irregular heartbeat but also described sensing God’s strong presence, which he said was a power he’d never felt before. A year after returning to Earth, he resigned from his position as colonel and established High Flight Foundation, an evangelistic ministry that spreads the gospel worldwide.

Charles Duke became the tenth astronaut to reach the moon a year later on Apollo 16. Following his return to Earth, Duke continued to serve in the US Air Force Reserve. On February 8, 2021, he preached at a special gospel gathering at Christian Ministries Church in Hot Springs, Arkansas, commemorating the 50th anniversary of his mission’s moon landing and urging truth-seekers to return to the true God.

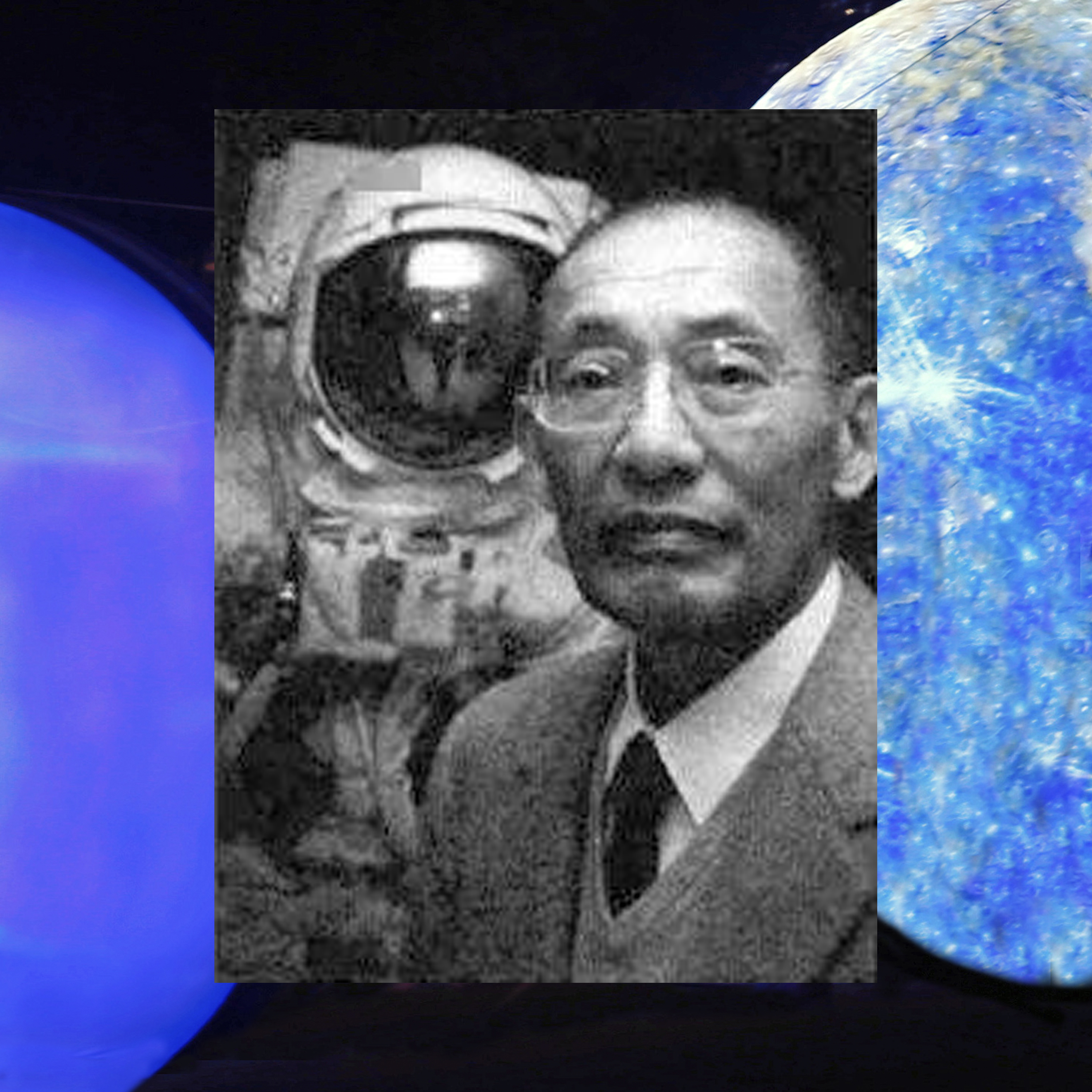

Among these luminaries in the Apollo program is another figure that might be lesser-known but no less accomplished: Chinese American scientist Xinyuan Tang, who was also known as Frederick Dawn. Called the “father of spacesuit fabric” for his soft, incombustible Beta cloth, Tang’s invention helped to address the flammability of the original Apollo spacesuit, which contributed to a fatal fire during the first Apollo mission that killed three astronauts.

Illustration by Christianity Today

Illustration by Christianity TodayTang was a devout Christian and a long-standing member of Clear Lake Chinese Church near Houston, which I previously served at. Despite his achievements, he remained exceedingly humble. “I praise and thank God, for unless the Lord builds the house, those who build it work in vain. It’s by God’s special grace and guidance that I have achieved what I did today, and may all glory be to God,” he said in an interview with a discontinued Chinese Christian publication, OK Magazine.

When I officiated at Tang’s memorial service, NASA dispatched a plane to fly a national flag over the Space Center to recognize his significant contributions to interstellar travel, and later covered his coffin with this flag.

Everlasting peace

Gazing at the moon during the Mid-Autumn Festival reminds me that faith in God has helped human beings achieve space explorations, and that peace and unity is not to be taken for granted or taken lightly.

The courageous Apollo 11 astronauts left a lasting message on the lunar surface with this plaque inscription: “We came in peace for all mankind.” This happened during the Cold War era, and the statement was a hopeful wish for peace in the realm of space exploration.

But our real example of peace is Jesus Christ, who sacrificed himself on the cross to reconcile man and God, as Ephesians 2:14 says: “For he himself is our peace, who has made us both one and has broken down in his flesh the dividing wall of hostility.”

In the Bible, this verse refers to removing animosity between Jews and Gentiles, and in today’s context, I see it as applicable to our tense geopolitical environment.

One event gives me hope that pursuing peace is possible amid a challenging political climate. China’s lunar orbiter—aptly named Chang’e—landed on the far side of the moon for the first time in 2019 and sent out a lunar rover (named Jade Rabbit, who is the celestial companion of Chang’e in the Chinese myth) to examine the moon’s surface. The China National Space Administration notified NASA of its exact coordinates, enabling the latter to photograph the Chinese space modules from above. You could say that this rare collaboration in lunar research between China and the US was akin to Apollo meeting Chang’e!

More recently, Christian astronaut Victor Glover is headed for the moon very soon. Next year, he will be piloting the Artemis 2 and paving the way for future NASA lunar missions. He will also be the first Black man from the American space agency to go to the moon.

In the vast expanse of the universe, where stars twinkle like distant dreams and the moon beckons with a soft glow, my prayer is that our words and deeds will also represent a profound sense of Christlike harmony and hope, like the Christian astronauts exemplified when they beheld God’s glorious creation in space.

And just as our reunions during the Mid-Autumn Festival wrap us in a warm embrace of goodwill and serenity, may our celestial—or spiritual—journeys be infused with the ever-present peace of Christ.

James Hwang spent 14 years as a research and development lab director at NASA’s Johnson Space Center. Following this, he felt called to ministry and served as the senior pastor of a church in Houston and as the executive director for an international Christian broadcasting ministry’s Chinese department. He now teaches at several seminaries and mentors doctoral students.