Abraham J. Heschel

Heschel (1907–1972) was a Jewish rabbi and theologian from Poland who escaped the Holocaust, lived in the US during the civil rights era, and taught for decades in New York City. The Prophets brilliantly captures how the Old Testament prophets offered an “exegesis of existence from a divine perspective.” Heschel also daringly probes the pathos of the Prophets’ God, whose involvement in history evokes divine love and anger.

John N. Oswalt

Whenever students or pastors ask me to recommend a commentary on Isaiah, I always mention this one. Oswalt offers a remarkable blend of attention to small exegetical details and the broader organization of the book, leaving readers with a strong sense of the thrust of each passage. Having gotten to know Oswalt, I can clearly see how his worship of Isaiah’s God has infused this commentary with richness.

The Lord Roars: Recovering the Prophetic Voice for Today

M. Daniel Carroll R.

For years, I’ve used Walter Brueggemann’s The Prophetic Imagination in the classroom. It powerfully captures how prophetic hopes and critiques speak into current realities. But I have been dissatisfied with his examples from Scripture. Carroll repackages the best of Brueggemann and invites us to experience the prophetic word through powerful samplings from Isaiah, Amos, and Micah, all while drawing upon his experience living for years in Central America.

Interpreting the Prophetic Word: An Introduction to the Prophetic Literature of the Old Testament

Willem A. VanGemeren

In the academy, it is common to study the prophets through historical and literary lenses. In popular Christianity, it is common to ignore such matters and just talk about Jesus. VanGemeren brings these elements together. He invites us to study the prophets within their original contexts, while also considering how the prophetic word speaks to future generations and fits into a redemptive-historical timeline that orbits around Jesus and retains hope for Israel.

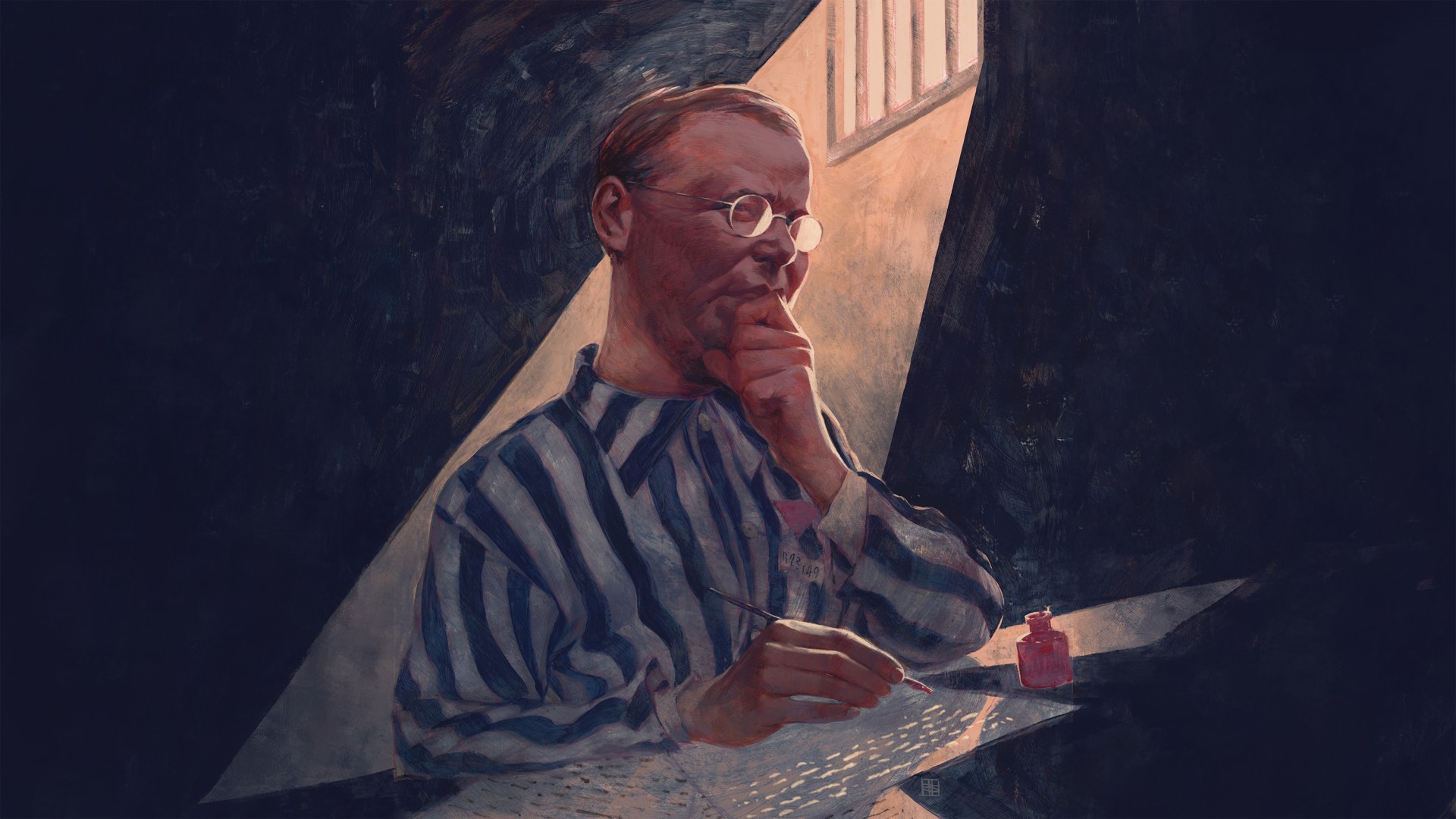

Dietrich Bonhoeffer

Bonhoeffer, of course, wasn’t an Old Testament scholar. But in 1937, writing to a church caving to the Nazi agenda, he put on the prophetic mantle and cast an uncompromising vision for following Jesus. He is a contemporary example of how the Prophets risked their lives to hold forth God’s Word.