In its first major case this term, the US Supreme Court seemed skeptical of arguments that Colorado could restrict counseling for minors regarding gender identity and sexual orientation without violating the Constitution.

Justices questioned whether the state’s 2019 law banning conversion therapy, along with any effort by counselors to help young patients alter gender expression or reduce same-sex attraction, amounted to viewpoint discrimination.

Colorado officials argue that professional regulation holds counselors to a high standard of care and protects children from a treatment with “no record of success.” Plaintiff Kaley Chiles called the restriction a “gag order on counselors” who want to address gender and sexuality from a place of shared convictions.

Today, over 20 states have bans similar to Colorado’s on the books, and the court’s decision could affect the landscape of Christian counseling. Other states have restrictions on the practice. Still, some states and municipalities have chosen to rescind or not fully enforce them.

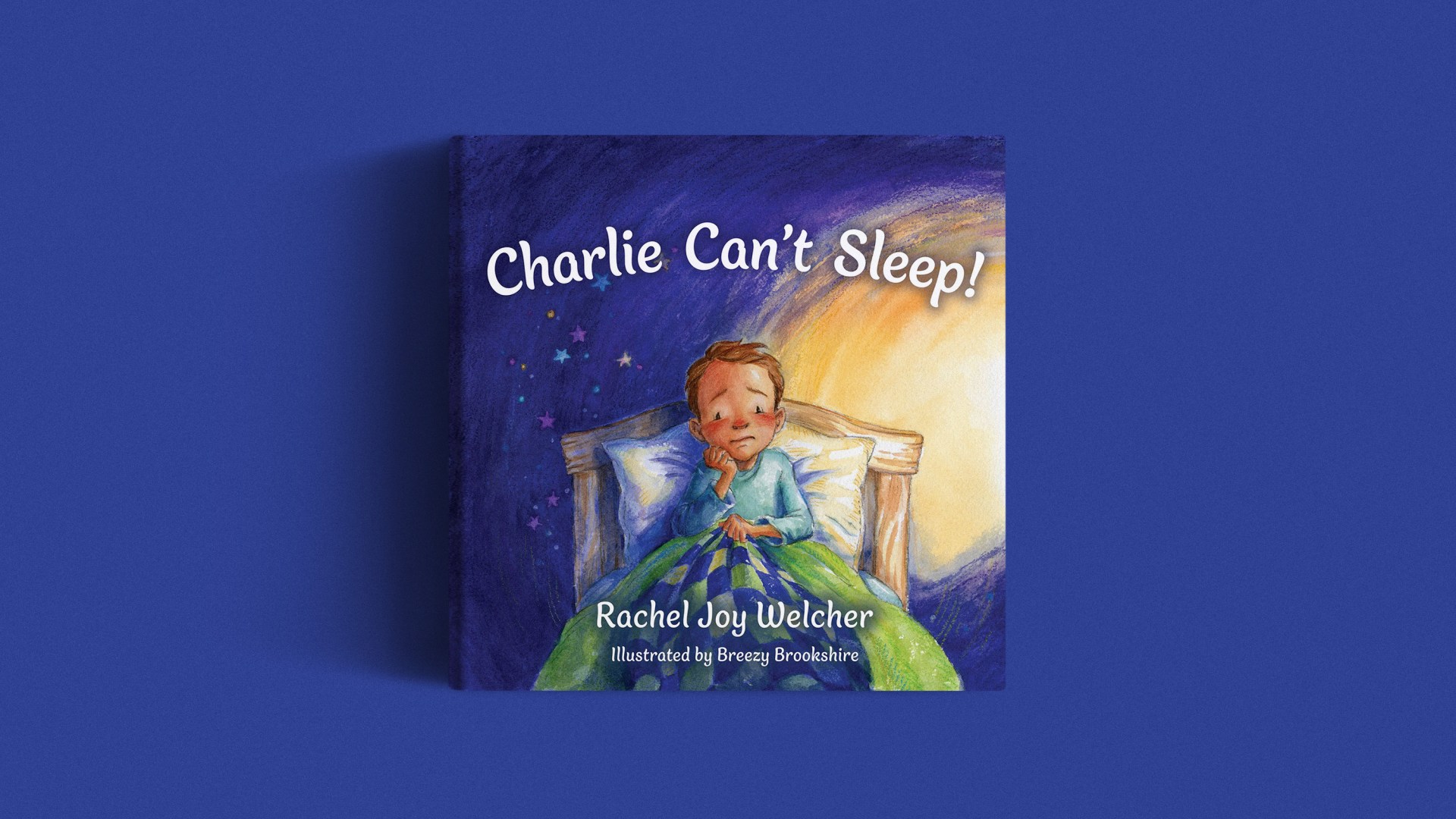

Chiles, a licensed professional counselor who serves Christian clients in Colorado Springs, said she doesn’t seek to “cure” clients who aren’t looking to change, but she does want to help those who come wanting to move away from unwanted attraction or feel more at home in their bodies.

“Many of her clients seek her counsel precisely because they believe that their faith and their relationship with God establishes the foundation upon which to understand their identity and desires,” Alliance Defending Freedom (ADF) legal counsel wrote in Chiles’s petition to the court to take her case.

The Association of Certified Biblical Counselors and the Family Research Council have backed her case, as has the Trump administration.

More than a decade ago, states began passing laws targeting hypnosis, shock therapy, and other controversial practices to alter same-sex attraction. Some of these legislative moves also included efforts to uphold traditional Christian perspectives on gender and sexuality. While clergy are exempt from bans in most cases, counselors who seek state licensure are not.

ADF is arguing that Colorado’s ban should be subject to the highest form of judicial review, known as strict scrutiny, to test whether it burdens free speech. Those who violate the law face up to $5,000 in fines per violation and can lose their license. Yet the law has never been enforced against Chiles or against any counselors in Colorado. ADF attorney Jim Campbell said Chiles has had anonymous complaints against her, alleging that she violated this law.

During oral arguments, Justice Department lawyer Hashim Mooppan defended Chiles’s form of talk therapy: “There is no conduct,” he said. “All that is happening here is speech.”

Colorado’s 2019 law forbids “any practice or treatment” from providing clients who are under 18 with treatment that would impact a minor’s “gender expression or to eliminate or reduce sexual or romantic attraction or feelings toward individuals of the same sex.”

Chiles challenged the law the same year it passed. Lower courts split on the issue, and a three-judge panel of the US Court of Appeals for the 10th Circuit sided with Colorado. The 10th Circuit ruled that “states may regulate professional conduct, even though that conduct incidentally involves speech.” The Circuit decided that the law cleared the “rational basis test,” which is a less strict form of review of constitutional challenges.

Chiles petitioned the Supreme Court last year, and in March it agreed to hear the case.

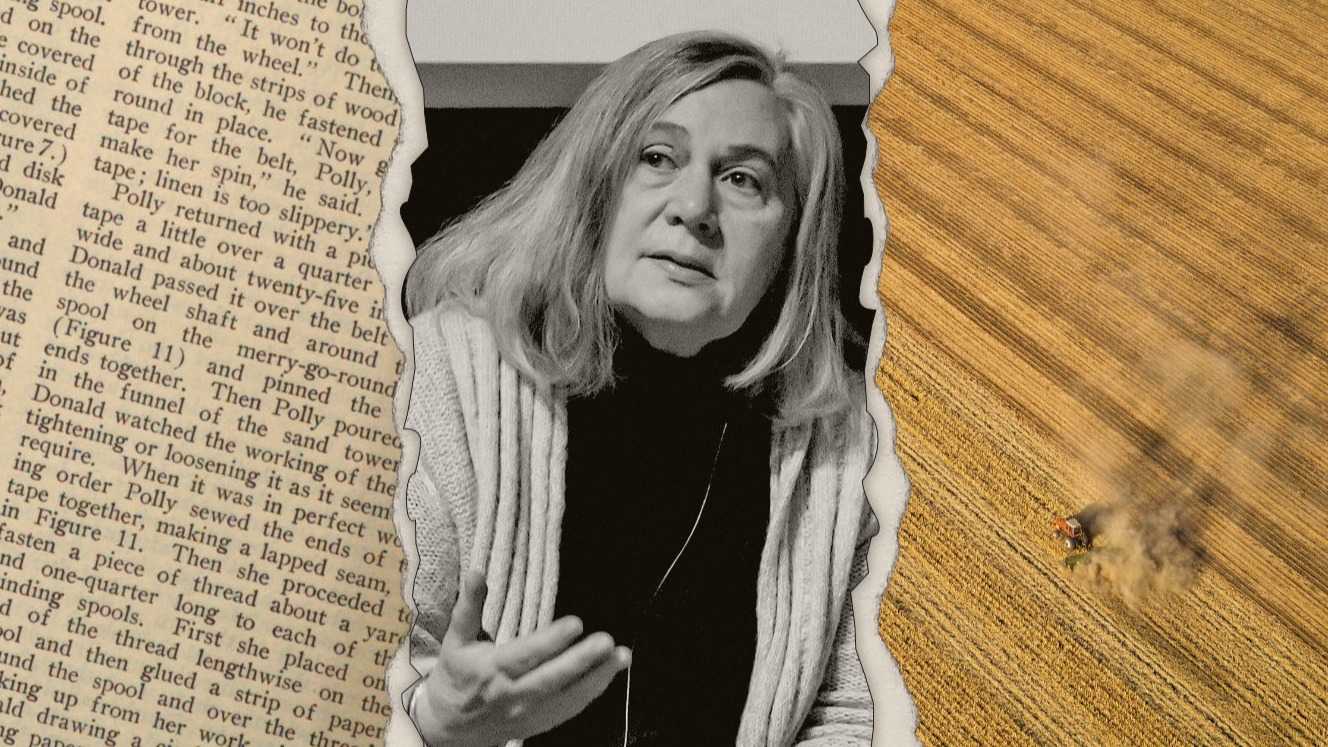

On Tuesday, Justice Amy Coney Barrett had a lengthy back-and-forth with the lawyer for Colorado. She laid out a hypothetical case where states take “different sides” on conversion therapy based on a dispute in the medical community.

“Let me describe medical uncertainty as competing medical views,” Barrett said. “And let’s say that you have some medical experts that think gender-affirming care is dangerous to children and some that say that this kind of conversion talk therapy is dangerous. Can a state pick a side?”

Colorado solicitor general Shannon Stevenson said the law is based on a stricter standard of care the state expects from medical professionals and that conversion therapy doesn’t meet that standard.

Even Justice Elena Kagan, who is in the court’s liberal minority, asked if these laws allowed states to practice a form of viewpoint discrimination. She gave a hypothetical scenario where a gay patient is offered conflicting advice from two different doctors. If only the doctor who wants to help patients accept their sexuality is permitted to offer care, “that seems like viewpoint discrimination in the way we would normally understand viewpoint discrimination.”

Stevenson responded that “medical treatment has to be treated differently.” She went on to argue that conversion therapy does not have adequate evidence behind it. But Campbell said the ban has left Christian families in Colorado without the counseling support they are looking for. The Supreme Court will hand down a decision by June or early July.

The case, Chiles v. Salazar, is one of the blockbuster issues the justices are considering this term. The Supreme Court will also consider the death penalty, voting rights, and whether states can restrict transgender athletes from participating on women’s and girls’ sports teams. Last term, the court’s conservative majority sided with a Tennessee law banning certain types of medical transition treatments for minors.