They dug up broken bits of lamp, the foot of a porcelain doll, a piece of what was once a bowl, and brick fragments from the Baptist church where African Americans worshiped while they were still enslaved. They excavated down to the foundation. Carefully clearing away the earth, they exposed the cross-stacked bricks at the base, dusted them off, and called Connie Matthews Harshaw.

Harshaw stood at the edge of the dig. A member of the historic black First Baptist Church in Williamsburg, Virginia, she had pushed for this project before anyone knew if they would find anything worthwhile. She had come a long way by faith. Now the archaeologists had something to show her.

“I see it,” she said. “We were here and we were strong. Through it all, we kept the faith, and we were hopeful. That’s a story to tell.”

Colonial Williamsburg, the living history museum that recreates the life of the 18th-century town that was then the capital of the colony of Virginia, is excavating a black Baptist church. The first phase was finished in November, and the second started this January, with the ultimate aim of reconstructing the building and recovering its history.

First Baptist was founded by free and enslaved African Americans in 1776, not long after the signing of the Declaration of Independence. It was illegal for black people to congregate and worship then, but they did anyway. At first they met secretly in a hidden brush structure. Then a Virginia woman decided to let the man she owned become a Baptist minister, and Gowan Pamphlet became the first ordained black man in America in 1772, a dozen years before the better-known Lemuel Haynes. Inspired by the Great Awakening, Pamphlet preached sin, salvation, and the equality of all before God.

A white family dedicated land to the worshipers, and First Baptist built a church. They prayed, heard the Word, and kept the faith through the Civil War, the failure of Reconstruction, the rise of “black codes” and Jim Crow, the Great Depression, and World War II.

Then the church was torn down in the 1950s to make way for the Colonial Williamsburg museum. The site was paved over for a parking lot. No one in charge thought the simple black church was worth preserving until more than a half century later, when Harshaw, representing the congregation that continues worshiping about a mile away, asked why not.

“There’s this placard about this church that was organized in 1776, but where’s the rest of the story?” Harshaw asked Cliff Fleet, the new president of the Colonial Williamsburg Foundation. He asked her what she would like to have happen.

“Uncover—literally uncover—the history of this church,” she said.

A lot of black Christian history has been buried in America, according to historian Paul Harvey, author of Christianity and Race in the American South and more than a half dozen other titles on African American Christianity.

Black institutions often haven’t had the resources to preserve their history. And white institutions “just didn’t care enough” in most cases, Harvey said.

As many historians have pointed out, the documentary record is often a reflection of who had power at a given time, not the product of a careful evaluation of what will be important. Starting in the 1970s, historians inspired by the civil rights movement started arguing that black history, and especially black religious history, was essential to understanding America.

“The neglect of black history…distorted both white and black American perception of who they were,” said historian Albert J. Raboteau, who wrote Slave Religion: The “Invisible Institution” in the Antebellum South about 20 years after the First Baptist Church at Colonial Williamsburg was torn down. “For a people to ‘lose’ their history, to have their story denigrated as insignificant, is a devastating blow, an exclusion that in effect denies their full humanity. Conversely, to ignore the history of another people whose fate has been intimately bound up with your own is to forgo self-understanding.”

In the years since, historians have gone to great lengths to recover what was lost. Raboteau combed through slave narratives, looking for every reference to faith. Harvey searched through travel narratives and white church records, looking for commentary on black Christians. Much of what he found was explicitly racist and dismissed African American faith as ignorant, but nonetheless it offered him glimpses of the forgotten Christians’ faith and practice.

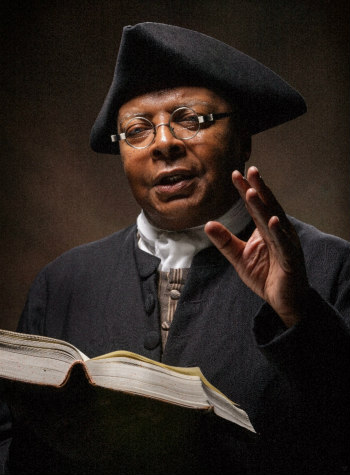

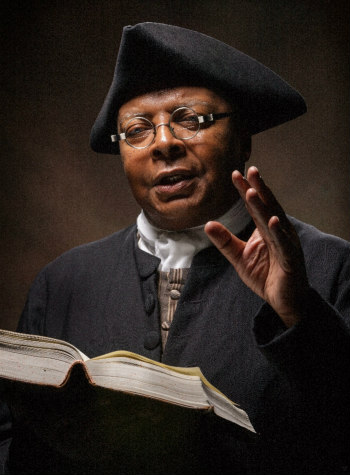

Other recovery efforts are even more creative. At Colonial Williamsburg, for example, several African American men have been performing Gowan Pamphlet for visitors to the living history museum. James Ingram, one of the reenactors, started in 1998 with a two-paragraph description of everything that was then known about the black Baptist minister.

“What really stuck out to me was that those couple of paragraphs were kind of conjecture,” Ingram said.

For the past 22 years, Ingram has learned everything he could about the world Pamphlet lived in. And he has tried to imaginatively access Pamphlet’s history by using their shared experiences.

Ingram is also Baptist, also ordained, and also a black man who grew up in Virginia. He writes sermons as Pamphlet and thinks about what he would have preached in the years after the Declaration of Independance.

He’s hoping the excavation of the church will give him more information.

Jack Gary, the director of archaeology at Colonial Williamsburg, hopes so too. But it’s slow work. Six professional archaeologists and several graduate students pull back the soil by hand, running it through a screen and collecting and documenting everything they find. They take pictures and draw maps, noting even the stains in the dirt, which might tell them something. They record bits of glass, distinguishing which come from windows and which from wine bottles.

Later, they will wash it all, curate it, and work together to interpret the whole assemblage of things left behind and buried at the First Baptist Church.

They dig up an ink bottle, which means someone at this church could write. A vanilla extract bottle, which means someone was cooking. Animal bones, which might mean there was a barbecue. And they slowly uncover the foundation of the old church.

“The building itself is probably not going to be an architectural wonder,” Gary said. “But our study of it provides the place where we can have these conversations about the early African American Baptists and what they went through. You can stand on that spot and it’s powerful.”

Connie Matthews Harshaw felt that right away.

“It is nobody but God,” she said. “He is all up in the mix.”

Daniel Silliman is news editor for Christianity Today.