American astronauts walked on the moon in 1969. CT celebrated the amazing achievement, while noting with disappointment that God received little mention.

Buoyed by the prayers, hopes, and determination of millions around the world, two American astronauts with Christian upbringing landed safely on the moon’s Sea of Tranquility.

It was possibly the most prayed-for event in human history, and the intercession continued as the astronauts headed back to earth.

From a Christian perspective, the absence of explicitly spiritual acknowledgements disappointed many. The late President [John F.] Kennedy had publicly asked God’s blessing on the American effort to reach the moon. God did bless the venture, but there was no immediate recognition of that fact or any utterance of thanksgiving for it, either from the astronauts on the moon or from President [Richard] Nixon in his earth-to-moon telephone call. …

Armstrong grew up in an Ohio Evangelical Reformed church which is now part of the United Church of Christ. But he has shunned churches in his adult life. … Edwin Aldrin, the second lunar pedestrian, showed that he takes his faith seriously. He carried along in the Columbia-Eagle spacecraft a morsel of communion bread which he ate while on the moon. Aldrin is an active United Presbyterian churchman.

Back on earth, evangelicals worried about sexual immorality. CT reported that, according to new social scientific research, “adultery has become almost the rule rather than the exception.”

Paul Gebhard, head of the Institute for Sex Research at Indiana University, which was founded by the late Alfred Kinsey, estimates that 60 per cent of married men and 35 to 40 per cent of married women have extramarital affairs. Both figures are up 10 per cent from the Kinsey reports of two decades ago. …

Increasingly, men seem to consider God’s prohibitions against adultery and other sexual deviations as relative matters that society is free to adjust when convenient. God did not prohibit adultery, however, simply because of some arbitrary whim or because adultery was harmful to Hebrew tribal life. He who gave us sex in the first place knows the bounds in which its fullest enjoyment can be realized.

CT editors noticed in 1969 that marriage vows also seemed to be changing. The bride’s traditional promise to love, honor, and obey her husband was seen as old-fashioned, and many were dropping “obey.”

The Christian woman considering marriage has a serious decision to make. Shall she insist on maintaining a separate independent identity by remaining single, or shall she find her fulfillment as a woman by becoming one flesh with a man, functioning as his helper as did Eve?

If this is indeed the biblical basis for Christian marriage, then it would seem that the marriage ceremony ought to reflect the uniqueness of Christian marriage. Historically this uniqueness was found in the marriage vows of the bride and the groom. While the man vowed to love and honor his wife, the woman was asked to vow that she would love, honor, and obey her husband. Inclusion of the vow to obey, if it is to be meaningful, must be preceded by adequate instruction. The bride must understand that the vow is not ceremonial. In premarital counseling sessions she must be taught the submissive role of the Christian wife. The minister has an excellent opportunity in the wedding ceremony itself to instruct the guests in the uniqueness of Christian marriage.

Public schools dramatically expanded sex education in the 1960s, sparking controversy across the country. CT reported that fundamentalist and ultra-conservative organizations stoked the furor—but said concerns were nonetheless legitimate. The magazine advised a moderate approach:

Certainly Christians should be keenly concerned about this important issue, and there are certain things about the approach of the Sex Information and Education Council of the United States (SIECUS) that they must question. But there is no excuse for irresponsible name-calling and accusation; such actions are foreign to the spirit of Christ. If criticism is to be constructive and effective, it must be informed. One cannot assume a charge is true solely because it was voiced by his favorite radio preacher.

Those who take the trouble to inform themselves discover that public-school sex education isn’t all bad. Investigation makes it downright difficult to believe that “Commies” are behind the whole thing, and the “pornography” often turns out to be some very un-titillating charts and diagrams. Furthermore, kids are getting sex education anyway, and sometimes what they get is pretty bad. Too often parents and churches have failed to face the problem. Perhaps the schools can be of great service in meeting a need in the lives of many young people. …

But the current programs of sex education are not free of major problems for the Christian parent.

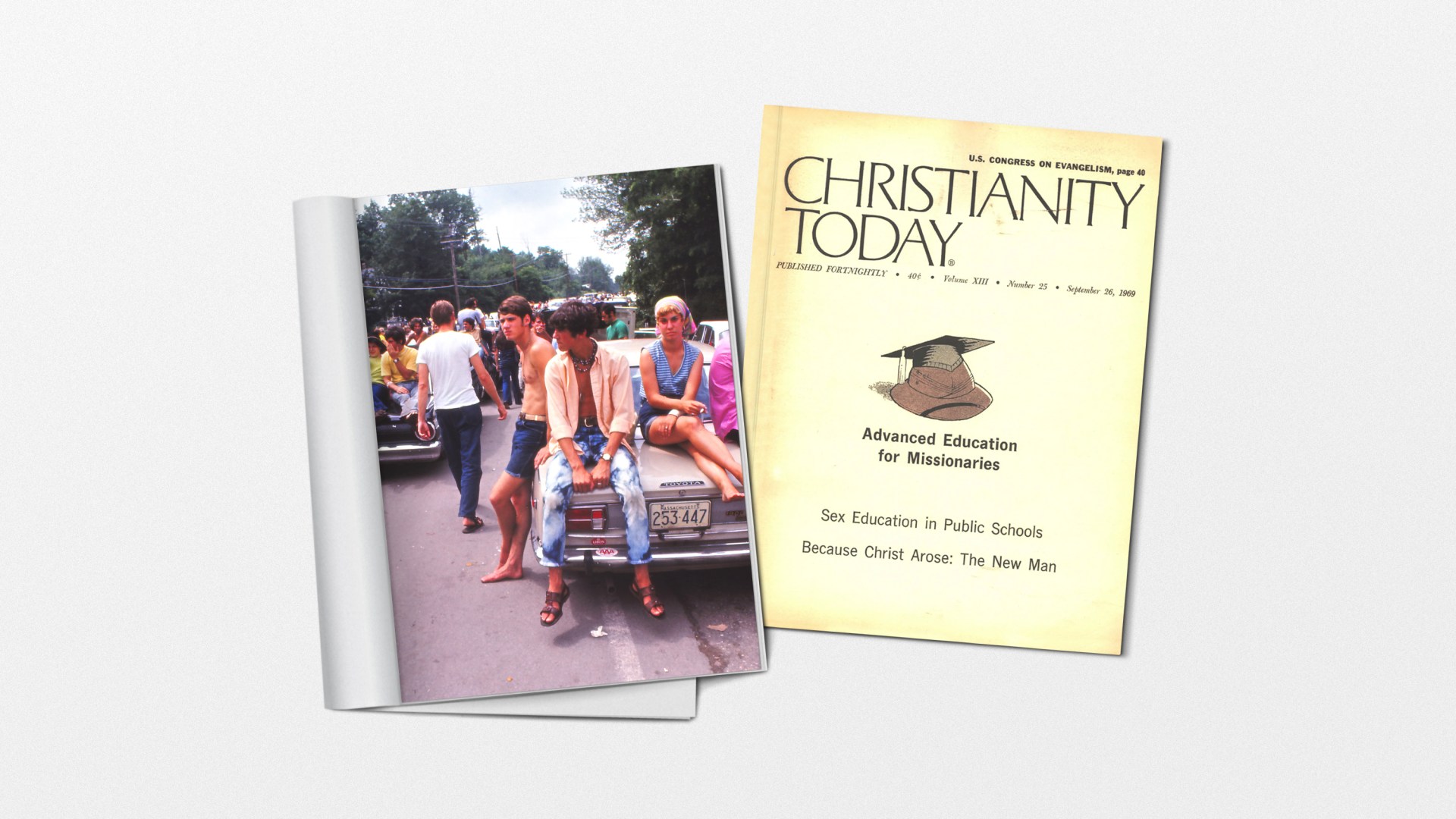

Many young people rejected traditional morality, embracing ideas of “flower power” and “free love.” CT reported the aspirations and spiritual longings at a massive music festival in Woodstock, New York.

Perhaps the most striking aspect of the festival was not so much the constant beat offered up by a number of outstanding rock artists, or the casual display of nudity, or even the free-wheeling use of illegal drugs. Rather it was the overwhelming sense of community experienced by the more than 400,000 young people jammed on the 600-acre farm for the weekend. They came in search of peace, of love, of oneness, of community, of a sense of belonging. And, in some measure at least, many claim to have found what they were looking for. …

We can express our dismay and disapproval at the tremendous traffic in drugs allowed to flourish at Woodstock. We can register our displeasure at the almost amoral attitude evidenced in the nonchalant indulgence in nudity and sex. … But the most effective ministry to the youth of our world will be a demonstration that in Jesus Christ they can find that which they seek.

CT also alerted readers to the surge of interest in astrology. The magazine pointed to the opening number of the new rock musical, Hair, hailing the “dawning of the age of Aquarius.”

Let no one think that to its cult the motif of the Aquarian Age is merely whimsical or eccentric. There is solid evidence that many among the architects of our pop culture take with extreme seriousness the division of history into segments ruled over by zodiacal signs. The philosophy of history projected here is about as follows: The 2,000-year period ending with the opening of the Christian era was the Age of Aries, symbolized by a ram, thought to suggest God the Creator. The following 2,000 years, symbolized by the fish and called the Age of Pisces, are considered a sorrowful age, represented by the death of Christ and marked by dissolution, water (tears) being its solvent.

Now, so the theory goes, we are at the dawning of the Age of Aquarius, which has been variously estimated to have begun in 1904 or 1933 or more recently … and is held to be a sort of new spiritual beginning, marked by promise of universal brotherhood, wide learning, and the shedding of hurtful inhibitions. …

Part of the current “cultic occultism” stems from a growing distrust of the rational in our time. Thus, we are seeing here a part of a larger revolt against reason that surfaces also in the rigid and unstructured demands of “far out” groups. … Time for March 21, 1969, estimates that there are some 10,000 full-time astrologers in the United States.

As the war in Vietnam continued, the US instituted a lottery-based draft of fighting-age men. CT urged Christians not to give up on American patriotism.

Christians ought to be the best citizens and the finest patriots. Certainly they have a prior allegiance to God Almighty. But this can only make them better Americans. They need not gloss over the nation’s defects or sweep its failures under the rug. They need not claim that their country is always right. When it is right, they will support it; and when it is wrong, they will love it and work to correct it. Even as the Apostle Paul could speak proudly of his Roman citizenship, so should every American Christian speak proudly of his. The day that patriotism ceases, that day we will have ceased to be a people. …

Let us rally behind our flag; let us love our country with all its faults; let us work to improve it with all our strength; let us defend it with all our resources; let us hand it on to generations unborn better than it was when we received it; let us instill in our children the hope of our forefathers for the ultimate fulfillment of their dreams. But above all, let us tell them that the greatness of America lies not simply in the achievement of the ideal but in the unrelenting pursuit of it.

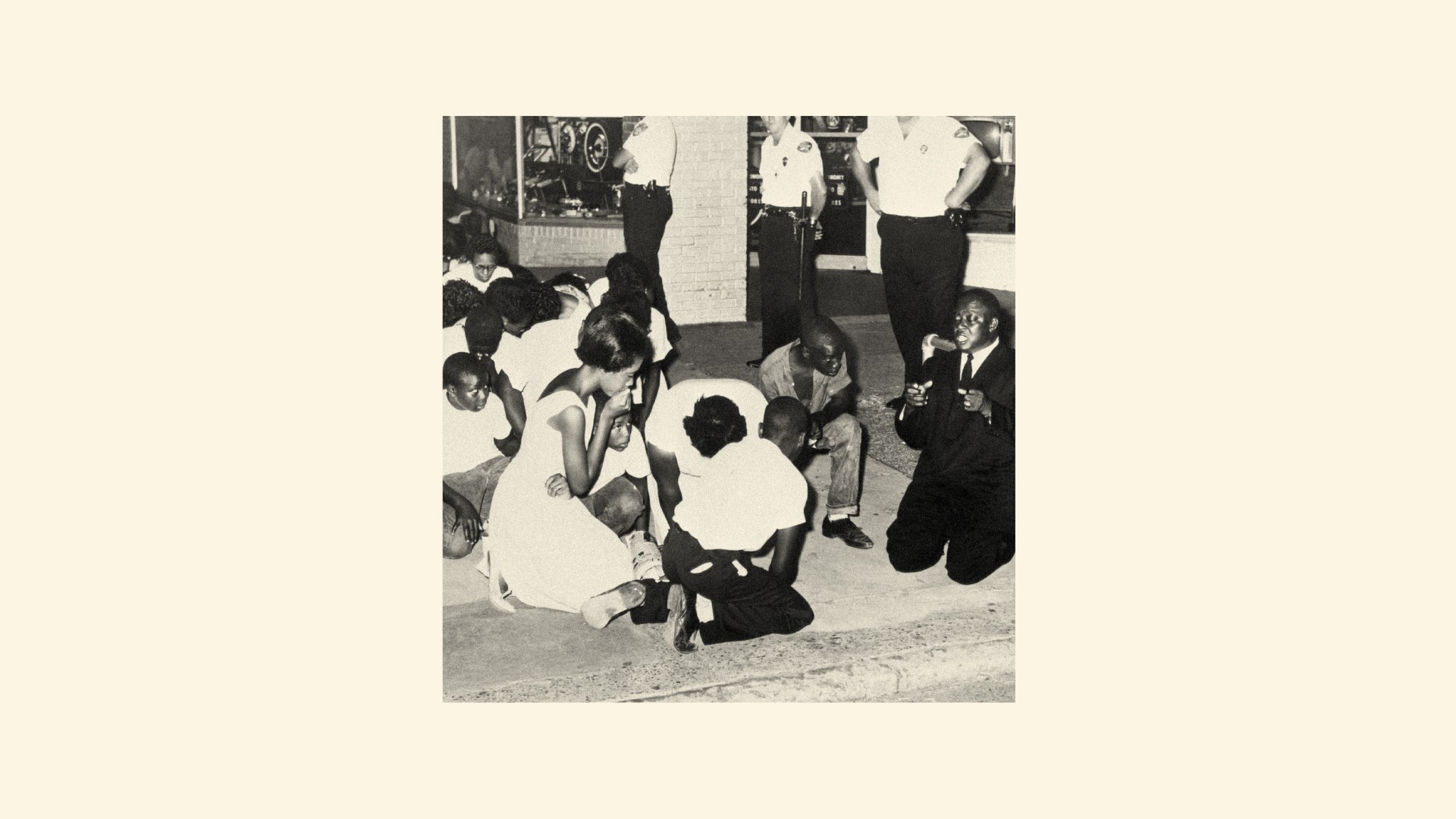

News of specific ways the nation had fallen short of its ideals in the Vietnam War left many Americans disillusioned. Journalist Seymour Hersh uncovered reports detailing how American soldiers murdered more than 300 unarmed women, children, and old men in a hamlet. For Christians, what was the “Lesson of Pinkville”?

We’re the good guys, and good guys just don’t do that kind of thing.

This kind of killing can in no way be excused or condoned, even though we may understand how the hell of war—and especially the kind of war being fought in Viet Nam—brings out the worst in men. We can remind ourselves that the enemy’s atrocities have been much worse, but somehow that doesn’t hide the appalling reality that American soldiers have been accused of gunning down helpless women and children. The facts must be brought out into the open. The offenders—if they can ever be accurately identified—must be brought to trial and punished, and every possible precaution should be taken to prevent a recurrence of such a horrible deed.

But even after punishment has been meted out, the fact remains: Americans acted like bad guys. It isn’t the first time that it’s happened, but the horror of this particular incident has confronted the whole nation with the fact that evil is not confined to the “commies” or the “fascists.” It lurks in the heart of every human being.

Theologian Karl Barth died in 1969. Though CT had often clashed with him, the magazine nonetheless called Barth “the man history will probably adjudge the twentieth century’s most important theologian.” An editorial careful considered the good and bad parts of his legacy, praising the good:

Barth … made perhaps his greatest immediate impact on theology with his Epistle to the Romans at the close of the First World War. In many ways this work was a turning-point. … This significant work helped to bring into fashion again, not merely the Scriptures in terms of content rather than historical circumstance, but the Reformers and many other thinkers whose writings had been neglected or disparaged in the age of liberal ascendancy. … Barth introduced a new vocabulary, new concepts, and a new bibliography as he engaged in a first and tentative effort at theological reconstruction. …

Although Barth never did fully return to the views of the Reformers on Scripture and at times seemed to open the door to universalism, yet we are grateful that he came back as far as he did.

The second great contribution of Barth was to provide a theological rejoinder to totalitarianism. This he did in the Barmen Declaration of 1934, which became the charter of the Confessing Church and an indictment of every form of ecclesiastical appeasement.

The controversial, liberal, “nonconformist” Episcopal bishop James Pike also died that year. CT reported on the strange circumstances:

Pike’s body was found on a rocky ledge two miles from the Dead Sea. … Prepared for the scorching desert with only a couple of bottles of Coca Cola and a map, [Pike and his third wife, Diane] set off shortly after noon September 1 in a rented car to “get the feel” of the wilderness where the Gospels say Jesus went to pray and where he was tempted by Satan. Their car became stuck on some rocks, and, after failing to free it, the pair struck off on foot. Several hours later, Pike, exhausted, lay down, and his wife left him in search of help.

CT also reported the strange story of a famous figure who didn’t die: Beatle Paul McCartney.

Fans have found buried in record grooves and on album covers … cryptic evidence that McCartney did indeed die, despite his recent disclaimers. Affirms the president of the “Is Paul McCartney Dead Society” at Hofstra University, “It’s all right there”—dozens of death symbols, like the picture of Paul sitting under a sign stating, “I was,” and the moaning (on one of the usually empty tracks between songs) that, reversed, sounds like John Lennon’s voice saying, “Paul is dead. Miss him.”

The current Beatle mystery is selling the group’s records and putting their pictures in American magazines, newspapers, and on newscasts. But some Beatle devotees claim McCartney will be resurrected. However disillusioned Americans might be, there was still hope people could find true hope in resurrection.