“If ‘Christian nationalism’ is something to be scared of, they’re lying to you,” Representative Marjorie Taylor Greene (R-Ga.) told her supporters in June. “And they’re lying to you on purpose because that is exactly the temperature change that is happening in America today, and they can’t control it.”

The Religion of American Greatness: What’s Wrong with Christian Nationalism

InterVarsity Press

304 pages

$17.10

Christian nationalism, once triumphant, will “stop the school shootings,” Greene claimed. It will lower crime rates, stop “the sexual immorality,” and guard children’s innocence and train them to want a traditional lifestyle. And it’s this wholesome movement of “Christians, and … people who love their country and want to take care of it” that “liars” in the media are deriding.

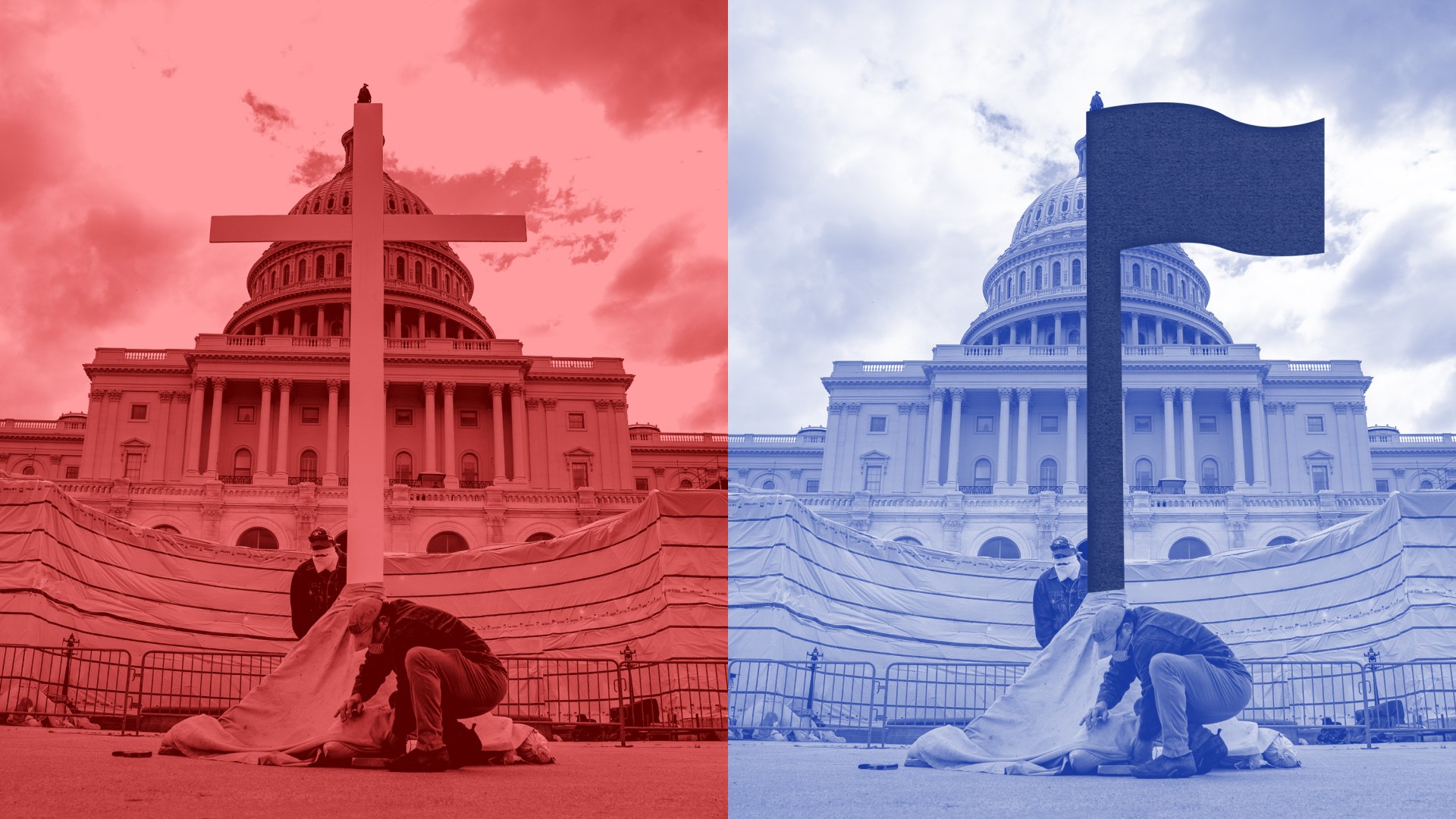

Greene is right on two counts: Christian nationalism is increasingly visible in American politics, and the movement has been much discussed in the press these past two years, particularly since journalists began to examine the Christian symbols and language used in the storming of the Capitol on January 6, 2021.

The rest of Greene’s account leaves more to be desired, but its emphasis on cultural dominance, political power, and protection of one’s own tribe—all topped with a flimsy veneer of Christianity—will be familiar to any reader of Paul D. Miller’s The Religion of American Greatness: What’s Wrong with Christian Nationalism.

Miller is well suited to explain why Christian nationalism, though not “something to be scared of,” is certainly something Christians should reject. He’s a veteran of the US Army, the CIA, and the George W. Bush administration—no stranger to patriotic milieus. He’s also a scholar, currently serving as a professor of international relations at Georgetown University’s prestigious School of Foreign Service, and an evangelical’s evangelical—a theological conservative who was baptized in a river, attended a Billy Graham crusade, and holds a special fondness for Chick-fil-A.

Greene painted critiques of Christian nationalism as deception or jealousy of nationalists’ rising power, but The Religion of American Greatness is neither. Miller is unsparing in his evaluation of the movement but sympathetic to its grassroots adherents. He has penned a useful resource for his main audience of educated evangelicals—pastors, church leaders, journalists, academics, and “other professional Christians”—whom he envisions using his work to fruitfully engage with their congregants, followers, and loved ones. In that primary goal, The Religion of American Greatness is an effective and compelling work, though Miller’s case for patriotic civil religion and Christian republicanism as the alternative to nationalism is not as convincing or well-developed.

The case against Christian nationalism

“Is the marriage of Christianity with American nationalism,” asks Miller, “a forgivable quirk over an unimportant doctrinal matter, a lovable excess in patriotism and piety?” Is it, in Greene’s phrase, simply Christians and “people who love their country and want to take care of it”?

“The burden of this book,” Miller writes, is to demonstrate Christian nationalism is not innocuous. It’s “to show that nationalism is incoherent in theory, illiberal in practice, and, I fear, often idolatrous in our hearts.” In all three aims, he ably succeeds.

The book begins with definitions and devil’s advocacy, delving into the nature of nationalism generally and its Christian, American, and (usually) white variant specifically. “Christian nationalism is not a catch-all term for any kind of Christian political advocacy,” Miller is careful to note. “The unique feature of Christian nationalism is that it defines America as a Christian nation and it wants the government to promote a specific Anglo-Protestant cultural template as the official culture of the country.” To play fair, he presents the case for Christian nationalism as represented by leading American and British thinkers of this ilk, including National Review’s Rich Lowry, First Things’s R. R. Reno (see CT’s review of Reno’s nationalist treatise here), and the late “clash of civilizations” scholar Samuel Huntington.

This exploration of Christian nationalism in its “ideal type,” as articulated by its more serious advocates, will be helpful for readers who want to be able to “steelman” the movement, to identify its influence in the political scrum, and to articulate why this ideal type and Christianity are, in Miller’s words, “separate, rival, mutually exclusive religions. They make fundamentally incommensurable claims on human loyalty. In its ideal type, you can either be a Christian nationalist, or you can be a Christian: you cannot be both.”

Yet, as Miller acknowledges, most Christian nationalists in America are not of the ideal type. The competition for their ultimate loyalty is far more muddled. Their nationalism is significantly a feeling, “a deep and profound bond … between church and nation that is experienced far more viscerally than it is intellectually or theologically,” and their politics are likely “an inconsistent mix of nationalism, conservatism, Christianity, republicanism, libertarianism, and more.”

For understanding that folk variant of Christian nationalism, Miller’s later chapters on the Religious Right and nationalism’s engagement with Scripture may be the most important in the book. They’re also the fieriest and most fascinating, particularly for readers like me, who encountered Christian nationalism for years without knowing its name. Reading this section felt like grouting tile: I had the bigger pieces, the book filled so many gaps—by recounting of the historic use of key Bible verses in American politics; describing the elite-grassroots split in US evangelicalism; critiquing the hermeneutical moves that fund America-as-Israel theology; and characterizing our country’s Jacksonian subculture.

But perhaps Miller’s single strongest argument, woven throughout much of the book, is his contention that Christian nationalism is actually a secular ideology. The thinkers he reviews speak of “Protestantism without God” and the adequacy of “America’s ‘ecumenical monotheism’” as the moral buttress for their cultural-political project. Their interest is in “the inherited norms, values, and habits of America’s Christian heritage” more than a living Christian faith. For the Christian nationalist, then, the “main point of sanctification” becomes safeguarding the nation, not “honor[ing] God by emulating his character.” And the nation, in turn, becomes the object of the nationalist’s worship. Though folk Christian nationalists may not believe themselves at risk of that idolatry, a “little yeast works through the whole batch of dough” (Gal. 5:9).

If not Christian nationalism, then what?

Early on, Miller writes that this is, hopefully, the first book in a trilogy on Christian nationalism, progressivism, and patriotic Christian republicanism. Despite those plans, he begins his apology for patriotism and republicanism as an alternative to nationalism in this initial work. Unfortunately—and perhaps because it requires book-length treatment—this portion is weaker than the rest. I’ll highlight three points.

First, the line between Miller’s conception of patriotism (good) and nationalism (bad) isn’t bright. At one point he says the difference between suitable Christian political engagement and Christian nationalism “can be subtle,” maybe even externally indistinguishable because the difference is “a matter of our own inner motivation.” In this vein, Miller pairs rejection of Christian nationalism with some lingering conception of the United States as a nation. For example, he argues that hiding away complicated historical figures like Thomas Jefferson “is tantamount to saying that there is no story of great deeds that binds us together, no shared history, and thus no nation” (emphasis mine).

It’s possible Miller is simply imprecise in his language, using “nation” as a synonym for “country” rather than sticking to his initial definition of it as a nationalist term, in which case this is a confusion of editing rather than thought. But Miller likewise promotes patriotic civil religion—not merely adherence to values like liberty and justice but cultural rituals to “evoke emotional loyalty to our country” like “schmaltzy patriotism on the Fourth of July.” And he does this while decrying the sacralization of the secular and denying that “the U.S. government is competent to sustain, create, or orchestrate a common national cultural template for a nation of 320 million people.”

Miller contends we need this civil religion because “we cannot live without some kind of group identity”; because “people must have something in which to take pride [and] if we deny them the ability to take pride in their nation, they will simply shift the locus of their loyalty to a subgroup, such as their ethnic or racial group;” and because “we cannot do without national stories. … To beat nationalism, we need to tell a better story.”

But what Miller doesn’t answer is why, in a book primarily for Christians, that story is not the gospel. Why is the solution “a political story”—and, if it must be political, why must it be on the national scale? Why is our group identity not the church? Why can’t we fight nationalism with loyalty to our congregations or neighborhoods? Why is a national patriotism the antidote of choice?

Second, Miller makes a persuasive argument that there’s an inexorable relationship between nationalism, identity politics, and culture war. “Nationalism,” he writes, “is the identity politics of the majority tribe; identity politics is the nationalism of small groups. In each case, groups of people defined by some shared identity trait look to the public square for status, spoils, recognition, and power.” These groups land in an escalatory culture-war spiral as each seeks to determine who “we” are and what “we” believe and do. By contrast, Miller argues, in a republican model of politics the state should eliminate those spoils of war by engaging in “cultural neutrality,” not “moral neutrality and state-sponsored secularism.”

But in distinguishing between kinds of neutrality, Miller leaves the biggest culture-war battles in play. Grounding his distinction in an assertion of natural law—which is unlikely to persuade those not already convinced of the theory’s merits—he says the state can’t be neutral regarding “human personhood and human sexuality,” and that here, “the public square is a ‘battleground of the gods,’ in which we can do no other than to advocate for our own fundamental beliefs.” But surely for many Christian nationalists today, those issues are the whole ballgame. These “limited” carveouts from cultural neutrality are exactly the matters that motivate Christian nationalists to seek state power to dictate national culture.

Finally, though he details the illiberalism of Christian nationalism, I’m not sure Miller realizes its present extent—and what it means for the prospect of shifting nationalists toward classically liberal Christian republicanism. Ending the chapter on “The Christian Right’s Illiberalism,” he writes:

Which is more important: republican institutions, or Christian culture? Having a free and open society, or having public symbols of respect for Christianity? Christian principles, or Christian power? Political liberty, or political victory? Christian nationalists would reject the framing of these questions as a false choice because they say the two sides must go together, while Christian republicans would be far more comfortable advocating for republicanism with or without a Christianized culture.

The notion that Christian nationalists would see this as a false choice may be true among some adherents of the “ideal type,” but at the folk level, I suspect, presented with these options, many Christian nationalists would simply choose victory and public respect. Consider their embrace of illiberal governance in Hungary—or recall Greene’s expectation that a political triumph for Christian nationalism would change Americans’ sexual behavior and reshape children’s plans for their lives.

American Christian nationalists like to talk about “liberty,” but I don’t think there’s much of a dilemma for them here, which means they’re further from republicanism than Miller may hope. That’s a small blemish in his argument, but a big recommendation of his book.

Bonnie Kristian is a writer and CT columnist. She is the author of a forthcoming book, Untrustworthy: The Knowledge Crisis Breaking Our Brains, Polluting Our Politics, and Corrupting Christian Community.