For today’s musical pairing, listen to Experience by Ludovico Einaudi. See video below. Note that all the songs for this series have been gathered into a Spotify playlist here.

“Then he took a cup, and when he had given thanks, he gave it to them, saying, ‘Drink from it, all of you. This is my blood of the covenant, which is poured out for many for the forgiveness of sins.’”Matthew 26:27–28

“Then he said to them, ‘My soul is overwhelmed with sorrow to the point of death. Stay here and keep watch with me.’ Going a little further, he fell with his face to the ground and prayed, ‘My father, if it is possible, may this cup be taken from me. Yet not as I will, but as you will.’”Matthew 26:38–39

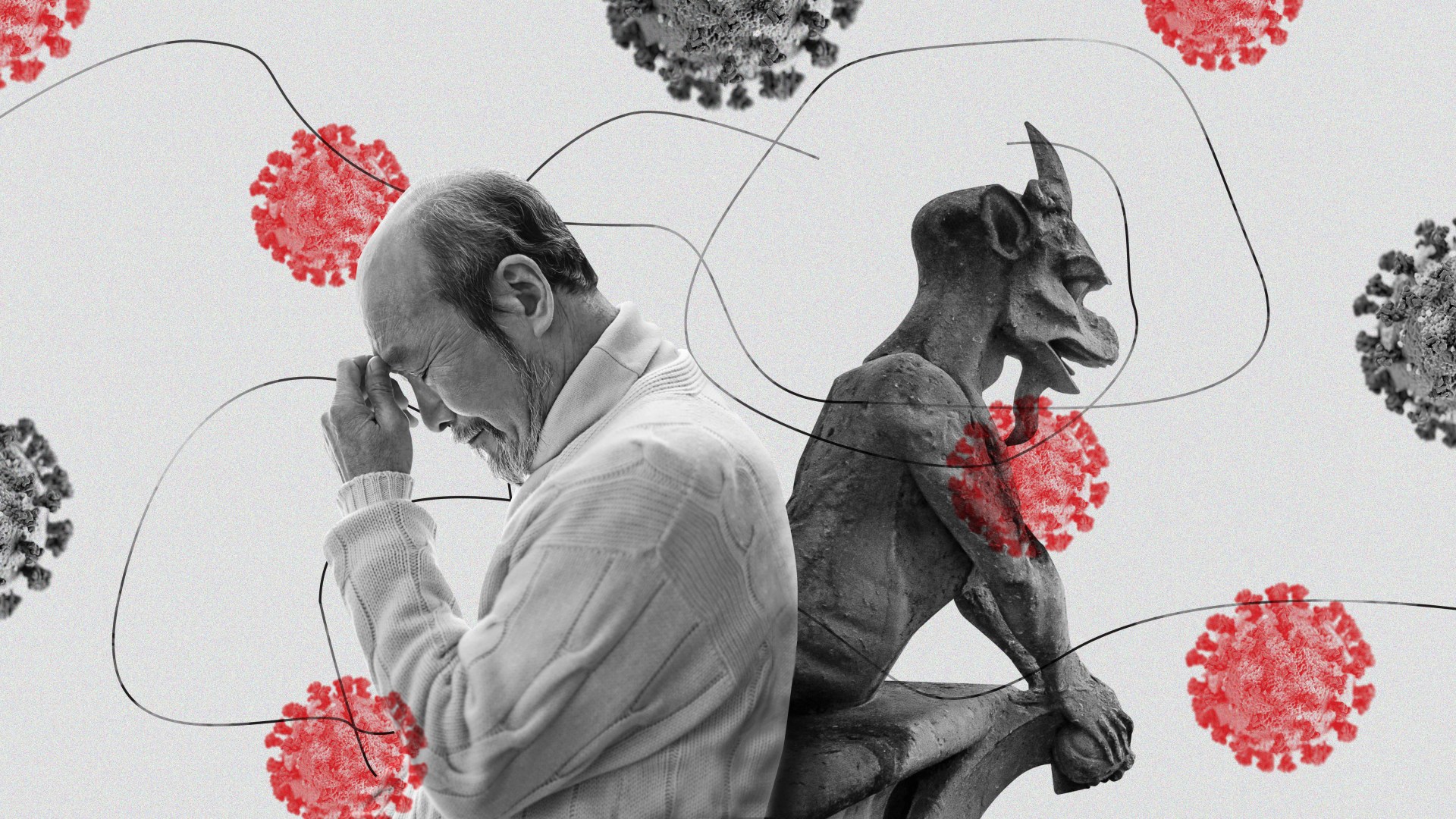

Day 8. 576,859 confirmed cases, 26,455 deaths globally.

The United States now has more cases of COVID-19 (over 86,000) than any other country in the world. The numbers of confirmed cases and fatalities have quadrupled over the past week as the disease continues to spread, symptoms surface, and testing catches up with reality. New York City is engulfed. Other cities will follow.

We are fighting a pandemic of disease and a contagion of panic simultaneously. We work to flatten the curve, but we cannot say where on the slope we stand.

We are reminded of you, Jesus, when you gathered in Jerusalem for a last supper with your disciples. You shared the bread of your broken body and the cup of your blood. With your blood, “poured out for many,” you established a fellowship of suffering. We share in your suffering and you share in ours, redeeming it from the inside out.

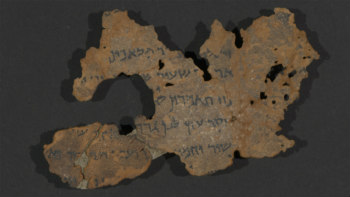

Later that night you crossed the Kidron Valley to the foot of the Mount of Olives, to the Garden of the Gethsemane. Gethsemane means “oil press.” You were about to be crushed for our sake, and you knew it. You brought your dearest friends partway with you, then left them behind to fall prostrate before your Father. The weight of what approached was so immense you wept blood with your tears.

“Let this cup pass,” you said. You did not welcome suffering. You did not celebrate its approach, even though you knew it was for the salvation of the world. You were willing to suffer for our sake—“Yet not as I will, but as you will”—but you did not love suffering for its own sake.

The cup of fellowship you shared in the Last Supper and the cup of suffering you accepted in the garden are the same cup—the cup of your blood, poured out for the world. Fellowship with you and suffering with you are inseparable.

Now, like you in the garden, we see suffering rising around us inexorably like a flood tide. We see the cup held out for us to drink.

If we must drink the cup, let us drink it with faith and join you in the fellowship of your sufferings. And yet we pray, as you prayed before us: Let this cup pass, O Lord. Let it pass, if it be your will.

Sign up for CT Direct and receive these daily meditations—written specifically for those struggling through the coronavirus pandemic—delivered to your inbox daily.