In this series

Steve Green, president of Hobby Lobby and chairman of the Museum of the Bible, is returning 11,500 antiquities to the Iraqi and Egyptian governments. The ancient clay seals and fragments of papyrus do not have complete documentation and may have been looted or stolen.

Green said he acquired the antiquities before the Washington, DC, museum opened in November 2017, when he didn’t understand the importance of proper provenance and trusted the word of unscrupulous dealers.

“These early mistakes resulted in Museum of the Bible receiving a great deal of criticism over the years,” Green said last week in an official statement. “The criticism resulting from my mistakes was justified.”

The announcement comes on the heels of a museum-funded investigation that found the 16 fragments of the Dead Sea Scroll on display at the Museum of the Bible are all forgeries, the latest in a string of controversies that cast a shadow on its collection.

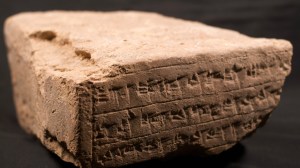

A year ago, the museum agreed to return 13 Egyptian papyrus fragments that were stolen from the University of Oxford. And in 2017, the federal government fined Hobby Lobby and ordered it to return thousands of cuneiform tablets and other objects, which were illegally taken from war-torn Iraq and brought into the US by a United Arab Emirates-based dealer who falsely labeled the shipments as ceramic tiles.

Museum officials hope this closes the book on its collection’s controversial beginnings.

“We understand that there’s been questions all along,” said chief curatorial officer Jeffrey Kloha. “We’d like to make the point that we’ve been involved in these conversations for two and a half years, three years. It simply takes time to work through all of the questions, talk to the right people, to look at different options.”

According to Kloha, the museum board ordered its staff to verify the provenance of all items in the museum’s collection in 2017, as well as all the items Green acquired that that never made it to the museum’s collection. Twenty curators and registrars worked for more than two years, checking documentation on the roughly 60,000 objects held in Washington, DC, and in a climate-controlled warehouse owned by Hobby Lobby in Oklahoma City.

Most of the objects are Bibles and printed materials, with a history that is easily traceable. The items that will be repatriated, mostly tiny clay seal impressions and fragments of papyrus, are thousands of years old, and harder to trace. Only one of the items being returned, a clay tablet recounting the Babylonian Epic of Gilgamesh, was ever exhibited in the museum.

“Very few of the papyrus have any kind of literary text at all,” Kloha said. “If there's any writing it's typically a documentary item, a receipt, or a letter. The vast majority are small, heavily damaged pieces.”

Officials in various Middle Eastern governments have been receptive to the museum’s repatriation efforts, Kloha said. The museum hopes good relations might open the way for future partnerships.

“We would be very interested in loans that bring some of their items here to the US, to help people here in the US understand the important history in these countries, the contributions that they have made and continue to make, to culture and to society,” Kloha said.

Critics of the museum and Green may not be so quick to forgive. For many, the entire Bible museum project is under a cloud of suspicion. However, some scholars of biblical antiquities have lauded the museum’s efforts to make things right.

Christopher Rollston, professor of Semitic languages at George Washington University, said he would take family and friends to the museum. “The serious blunders of the museum, these breeches of ethics and law, are part of the past,” he said.

Lawrence Schiffman, professor of Hebrew and Judaic Studies at New York University, agreed.

“The museum deserves to be praised,” Schiffman said. “From the day it opened, the museum told the truth. They have been completely kosher about this.”