Debates about bringing Santa Claus into church are perennial. But what about the Easter Bunny? We asked a variety of church leaders across the US to weigh in on whether this is good outreach, family friendly fun, or a distraction from message of Easter.

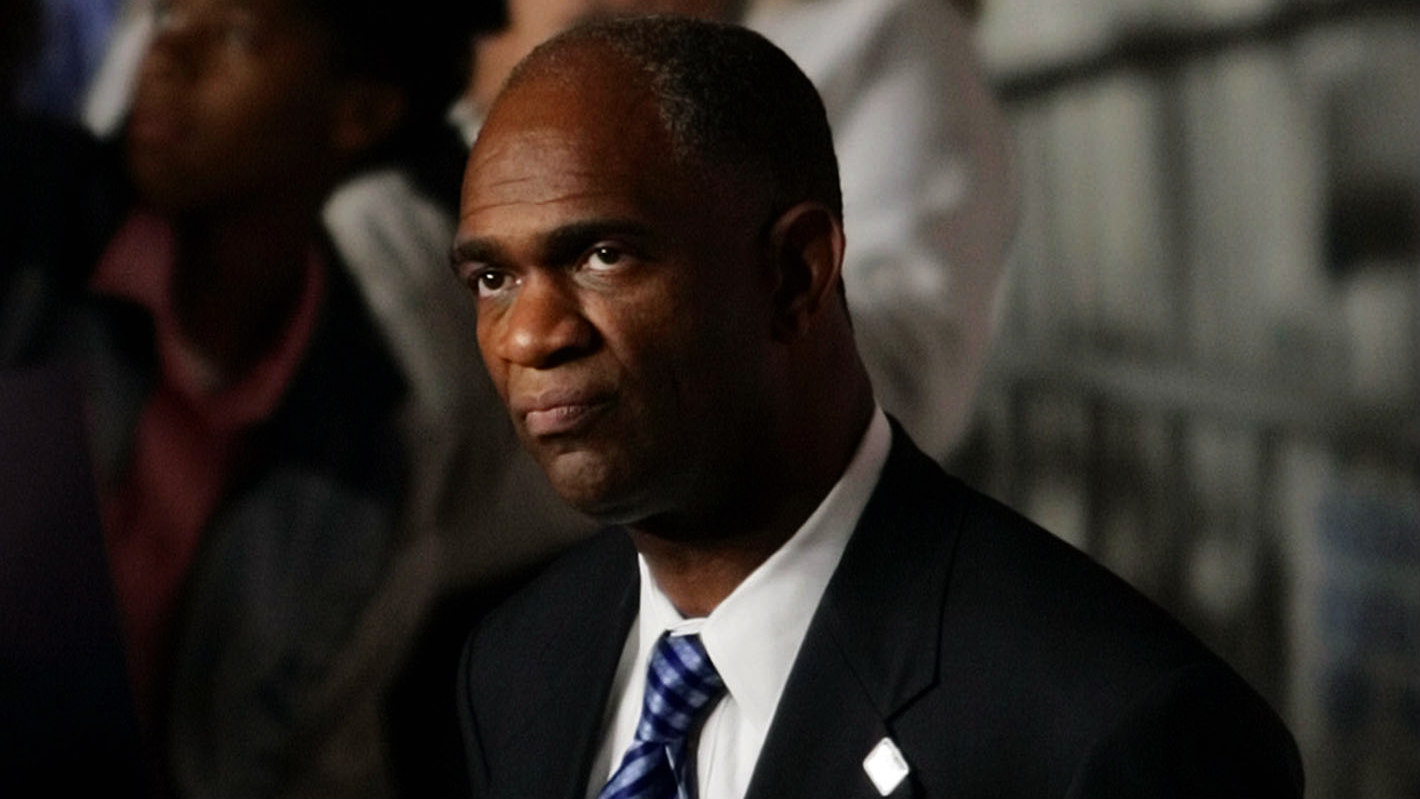

Caleb Campbell, pastor of Desert Springs Bible Church, Phoenix:

I think it’s totally fine as part of the egg hunt for kids or a prop for the sermon. However, I don’t think the pastor should do the sermon in a bunny suit—unless it’s a really good sermon.

Kevin Georgas, pastor of Jubilee Baptist Church, Chapel Hill, North Carolina:

It’s not something I’d get very worked up over. I wouldn’t have the Easter Bunny be a part of our worship liturgy but am not opposed to having an event where people take pictures with the Easter Bunny.

Amy Palma, pastor of South Fellowship Church, Littleton, Colorado:

While the Easter Bunny can be used as a tool to invite families outside the church’s walls, we have chosen not to do so. We do a glow-in-the-dark egg hunt event for that purpose, and to be honest an Easter Bunny in the dark would probably be a little terrifying!

Bobby Breaux, pastor of Twin Cities Church, Grass Valley, California:

Grace allows the church to have an Easter Bunny, but I do not think it is the best strategy for the holiday. Our egg hunt is offsite at an elementary school—so in children’s minds, not much association is made to the church. Our community sees it as a service we provide for free and an avenue where we advertise to young families our Easter church services.

Wendy Coop, host of the podcast Dear Pastor: Notes from a Virtual Pulpit:

Let’s not confuse the kids with the Easter Bunny unless we’re ready to explain why people even associate it with Easter. I’ve been at churches that had Easter egg hunts, and I was left explaining to the kids why bunnies don’t lay eggs and what this even has to do with the Resurrection. Unless you’re willing to go all in with the explanation, keep it focused on Jesus.

Darrell Deer, pastor of College Heights Baptist Church, Elyria, Ohio:

The Easter Bunny at church is over the line as far as I’m concerned. It confuses the issue and detracts from the real meaning of Easter. In this age when Christian distinctives seem to be blurring, it is important to hold onto and elevate the crucifixion and resurrection of Jesus.

Zeb Balentine, professor of worship arts at Bryan College, Dayton, Tennessee:

Personally, as a father of three, I would rather my church put the effort into communicating the message of the Resurrection than bring in an Easter Bunny. A church will have to decide if they want that holiday to be Christ-centered or not. An Easter Bunny certainly is not.

Katy Drage Lines, pastor of Englewood Christian Church, Indianapolis:

It’s not appropriate. It seems to me that if Christ’s resurrection is the exhibition of the power of God destroying death and offering reconciliation to all creation, then celebration of that event is diminished by a consumer-oriented bunny handing out chocolate to satisfy a sweet tooth.