President Donald Trump’s governing style is chaotic, confusing, and abrupt. Compared to past presidents’ methods, his may be different more in degree than in kind, as the executive branch has become increasingly powerful, complex, and slow to fix problems. But one bright spot, easily missed in the recent hodgepodge of executive orders from the White House, is that some of Trump’s reforms are grounded in—or at least unwittingly resonant with—the reality of how poverty fighting actually works.

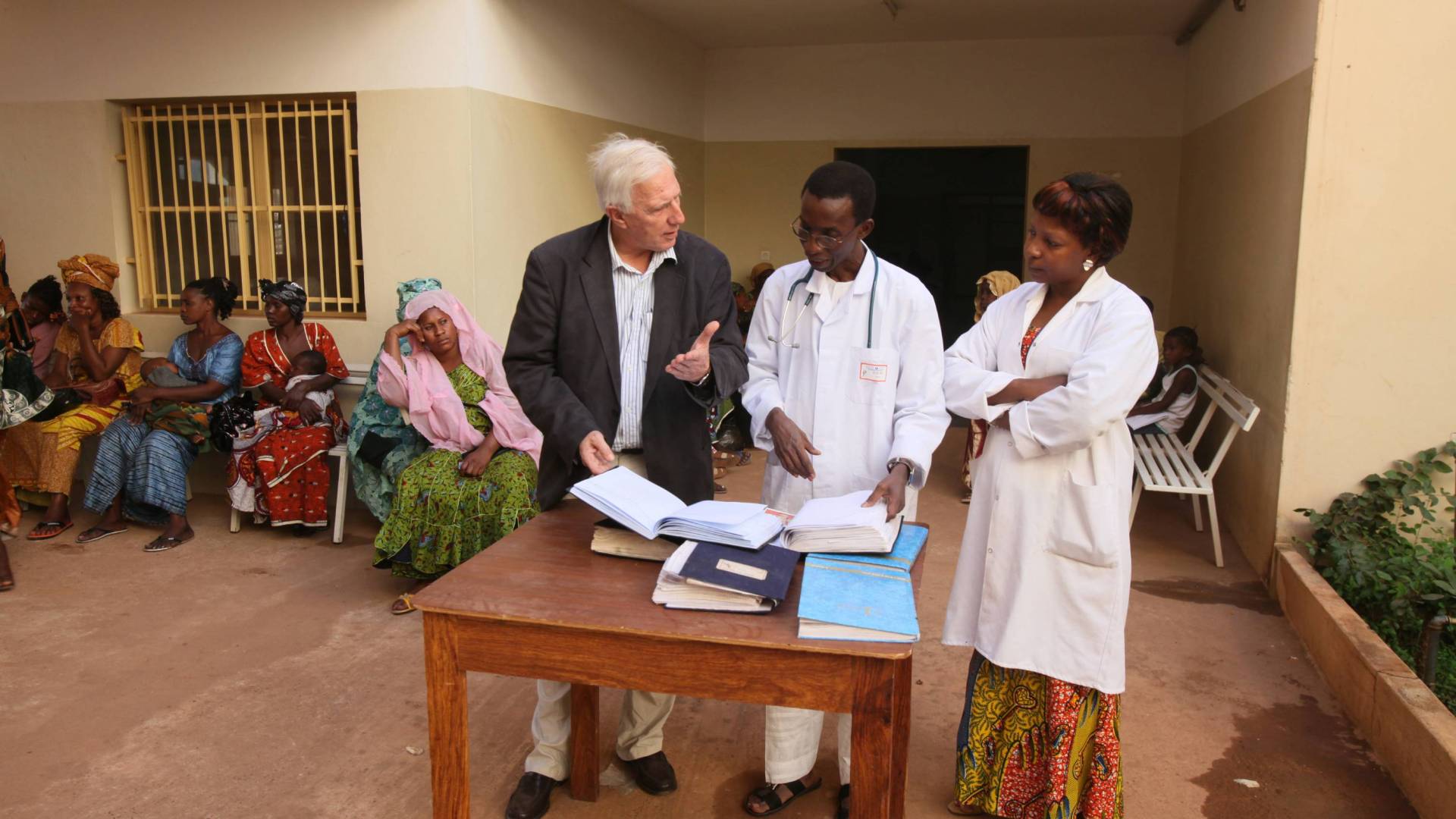

While some Christian commentators lament cuts to the USAID budget, for example, international economists and social scientists have long critiqued (here and here and here) the failures and even harms of humanitarian international aid. This model was due for reassessment long before Trump’s first administration, let alone his second. Unfortunately, White House adviser Elon Musk’s sledgehammer approach has obscured such legitimate concerns by suggesting that cuts are about nothing more than reducing the federal deficit.

The truth is that USAID makes up about 0.3 percent of the federal budget. Pre-Trump, substantive critiques of USAID came from the political left as much as the right and, alongside concerns about high costs and disincentivizing work, have included accusations of neocolonialism, harm to local economies, and aid to corrupt dictators in recipient countries. The danger in simplistic “USAID bad” rhetoric from the White House is that Trump’s critics will merely respond with “USAID good.” What about “USAID improved”?

A similar dynamic may happen with domestic social programs too. America’s antipoverty interventions tend to entail invasive micromanagement of the personal lives of the poor. These programs often discourage decisions that lead to long-term wealth-building, and a disturbingly high percentage of their budgets go to middle-class bureaucrats rather than program recipients.

As federal programs are cut, many Christians lament the loss of support to the poor, the widow, the fatherless, and the stranger. There is a good and biblical impulse here, but a totalizing lament could serve to defend government-funded efforts with the same sledgehammer approach DOGE is using to attack them. Just like foreign aid, domestic aid deserves scrutiny and reform that deals in reality, not quick political “victories.” We need careful distinctions between helpful and unhelpful programs to guide meaningful reform.

This is not a partisan argument. While critiques of the welfare trap might ring conservative in our ears, many on the left are just as incensed at the way the system is set up, even if they’re more sanguine about broadening social safety nets. For example, both right and left critique benefits cliffs, which make smart moves like work, promotion, and marriage economically irrational. (Picture getting a small raise at work, only to find out that you just exceeded the low-income requirement for an important benefit such as food stamps or childcare. Suddenly, your small raise turns into a massive pay cut, and it makes more sense to quit or sabotage the job than to keep plugging away at it.)

Benefits cliffs are what economists call a perverse incentive or moral hazard, because they incentivize short-term decisions that undermine long-term advancement. This critique is ubiquitous, but we simply have not managed to backpedal out of our current system and prevent this dynamic in US social spending, even though experts have suggested various ingenious schemes. A safety net should be just that—something to fall back on in desperate times—not a net that entraps people and keeps them dependent. Solving this long-standing problem would actually be a good use of DOGE.

Unfortunately, private antipoverty efforts often have similar problems. There are unique concerns with state projects, but concerns about private charities’ spending to address domestic poverty are also growing. Free-market conservatives insist that civil society institutions can offer the relationships, networks, and moral formation that make a genuine difference in poverty, especially in an American context where social connection is the hinge on which one’s economic prospects often turn. That sounds very sensible, but oddly, this model often isn’t often what we see.

Conservatives need to be reading great works like Bob Woodson’s Lessons From the Least of These and Bob Lupton’s Toxic Charity. These books outline how destabilized neighborhoods require investment in grassroots leaders from the neighborhoods themselves. Grassroots leaders have the local knowledge, personal investment, and credibility to do what no outsider could possibly accomplish. They need to be supported by those who have greater access to resources and networks. Woodson and Lupton have been widely praised, but in practice Americans still send charitable dollars to a lot of the same old models that don’t really work.

Going forward, Trump or no Trump, public or private, focus on the local is vital. Warm feelings about nice-sounding programs aren’t enough. Genuinely transformative efforts are long, slow, and local. Those with middle-class backgrounds and college educations are not more capable than the men or women from the block when it comes to rebuilding poor neighborhoods.

This bewildering political moment might be an opportunity for us as Americans to recalibrate how we dream of stabilizing our most struggling neighborhoods, both at home and abroad. But we must determine not to be deceived by partisan politics or defensiveness about the charitable efforts many of us have supported till now. Those distractions will keep us from making a redemptive turn.

Rachel Ferguson is director of the Free Enterprise Center at Concordia University Chicago, coauthor of Black Liberation Through the Marketplace, and affiliate scholar at the Acton Institute.