To ascertain an authentic view of the state held by Christians is not as easy as might at first appear. The difficulty arises primarily from the fact that the New Testament, which forms the basis of the Christian belief and practice, is not a political book. It affords only a scant handful of passages which could be said to supply the Christian with a clear idea of what the civil state is and what his responsibility to it and participation in it should be. Again, in accounting for prevailing concepts we must allow for the continuing influence of the Judaistic tradition which preceded the Christian formulation, for the undoubted abiding influence of surrounding pagan philosophies and for effects of historical events which have tended even among Christians to alter or change the original Christian view.

In beginning with Jesus, we note the classical reference to his saying, (Matt. 23:21; Mark 12:17), “Render to Caesar the things that are Caesar’s and to God the things that are God’s.” From the context we know he spoke of the obligation of men to pay taxes to the existing government. In the light of Paul’s detailed admonition to the followers of Jesus to support civil government, found in Romans, chapter 13, we construe the Apostle’s words to include more than payment of taxes, or an obligation to “render to all their dues, tribute to whom tribute, custom to whom custom, fear to whom fear, honor to whom honor.” This injunction is based by Paul on the prior premise (verse 1) that every one must be subject to the higher powers, civil powers being ordained of God, there being no power but of God.

The State Is Necessary

Neither in Jesus nor in Paul is there any direction that obedience shall be conditioned on the form of government, whether monarchical, democratic or any kind whatsoever. In other words, theirs is a definite recognition of the necessity for the state as a means to social order. Very few Christians—with exception of the Quakers at one time—have ever held to a stateless society. Christians universally have stood against anarchy. Paul offered his argument for this position in Romans 13:3, “For rulers are not a terror to good works, but to the evil.” Peter likewise argued, 1 Peter 2:13–14, “Be subject for the Lord’s sake to every human institution, whether it be to the emperor as supreme, or to governor sent by him to punish those who do wrong and to praise those who do right.” Although Jesus and the apostles lived under very corrupt governments, they counselled submission to them rather than risk anarchy, which would be worse. This rejection of a stateless society differentiates Christianity from communism, for communism in theory looks to a time when “the state will wither away” and there will be no need for its police power to coerce. (U.S.S.R., A Concise Handbook, Edited by Ernest J. Simmons, Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 1947. p. 164).

It is significant that Jesus and Paul made their pronouncements before organized Roman persecution of Christians began, while Peter entered his in the midst of the severest persecution. John, in Revelation 13, confronting the worst of government hostility toward his faith, suggested only passive resistance, not political or military resistance. This would show a fixed Christian idea concerning the state.

The Right Of Revolution

The latter Scripture, however, may have contributed to a later interpretation of these cited passages for supporting the doctrine of the right of revolution. Revelation 13, if the common identification of the “beast” mentioned with the Roman Empire be allowed, unquestionably permits rejection of the empire and its rulers, if indeed it does not sanction overt action against them. The later upspringing acceptance of the right of revolution under sufficient provocation grew to expression when the specific scriptural injunctions came to be considered in the light of the entire body of Scriptures. The New Testament as a whole does not countenance the absolute state presently denominated totalitarianism. It limits the state by the words, “there is no authority except from God.” It is not possible to conclude from Romans 13 that there is divine sanction for every existing order or that such cannot be changed, for the authority of the state is always subordinate to the over-riding authority of God. Therefore the Christian conscience finds voice in Acts 5:29, “We must obey God rather than men.” In this connection it is appropriate to quote John C. Bennett:

The warning against anarchy has often been understood in the sense that the most that Christians should ever do by way of resistance to even the most tyrannical and lawless state is to refuse to obey and to take the consequences in the form of punishment and persecution. Even Luther and Calvin, who were not passive by nature, had great difficulty in suggesting anything more than passive resistance to the most tyrannical authorities. Both, however, in different contexts did provide for active resistance on the part of lower political authorities against higher authorities. The loophole for active resistance, even for violent revolution, became a major factor in the history of Calvinism; and as a result, Calvinism helped to inspire revolutions in many countries, including Scotland, England, Holland and the United States. In the period of the National Socialist state, many Lutherans approved of active political resistance in Norway, Denmark and Germany. Roman Catholics have in general had less difficulty than Protestants in approving active political resistance where political authorities have threatened the life or freedom of their church. (The Christian As Citizen, New York: Association Press, 1955, pp. 49–50).

Separation Of Church And State

On the other hand Protestants, particularly the left-wing Puritan independents, took the lead in disestablishing the church and in separating the church from the state. Baptist Roger Williams was moved by dislike of the state controlling the church, while Episcopalian Thomas Jefferson revolted against church control over the state, with the result that the American Republic set the pace for separation of church and state for most modern countries. Both Williams and Jefferson agreed that the membership of a state and a church are quite different, the constituency of the state being the population and that of the church being those gathered out of the population by reason of their spiritual qualifications. They also agreed that the functions of the church and those of the state being secular are under enforcement of police powers. Those contending for church-state separation assert that it has lessened corruption which has characterized union of church and state wherever such has existed. The United States Supreme Court has declared that in America separation of church and state has proved best for the church and the state. Thus convincing proof by historic experiment has been given against the hoary contention that union of church and state is essential to national unity.

Although advocates of church-state separation frequently give Jesus’ words, “Render to Caesar the things that are Caesar’s, and to God the things that are God’s,” as authorization for their belief, it is only fair to point out that the real reason for the new order originated in the struggle for freedom, both in the battle for religious liberty for believers and in the demand for political freedom on the part of citizens upholding the state. This is not to affirm that the plan is contrary to Christianity. Quite the opposite, adherents believe that while not explicit in the Christian system, it is implicit in the Christian teachings.

Secular State Is Modern

It is a fact, however, that the differentiation between the purely religious nature of the church and the essentially secular functions of the state is a comparatively modern development. No differentiation was seen in Babylonia, Egypt and the most ancient civilizations. Josephus wrote:

Some legislators have permitted their governments to be under monarchies, others put them under oligarchies and others under a republic form; but our legislator (Moses) had no regard to any of these forms, but he ordained our government to be what, by a strained expression, may be termed a theocracy, by ascribing the authority and power of God. (Against Apion, Book II. paragraph 17, in Complete Works of Josephus. New York: World Syndicate Publishing Co. X, p. 500)

The Hebrew Repudiation

It will be remembered, however, that the Hebrew theocracy gave place to monarchy under King Saul, and that after the Exile of the Jews, fearing control of their religion by the heathen states in which they lived, forever thereafter renounced union of church and state. Those same heathen states long before and for a millennium after, maintained union of church and state. In primitive Greece, as elsewhere, there was no distinction between the religious and the secular. The king, in his capacity as head of the state, was also the chief priest and the guardian of religion. Unity of religion and the state was observed in the Greek city-republic. Socrates was condemned to death for religious heterodoxy. In pre-Christian Rome the ancient mixture of state and religion obtained, and in the later empire the emperors were deified and worshipped, to the horror of the Christians.

Considering world-wide practice, it was not surprising that when Constantine the so-called Great in 313 A.D. accepted Christianity, he prescribed it should be the religion of the state and that he forthwith commenced to persecute all dissenters unto death. While it must be admitted that by the stupendous event of Constantine’s conversion the Christian church acquired immense prestige and grasped unmeasured opportunities, it nevertheless suffered tragic deterioration in quality and impairment in its fundamental principles. Tertullian when persecuted preached, “It is a right and privilege of nature that every man should worship according to his convictions;” but he subsequently argued, “Heretics may properly be compelled, not enticed to duty” (Religious Liberty: an Inquiry, by M. Searle Bates. New York: International Missionary Council, 1945, pp. 137–138). Augustine, when a youth in North Africa pleaded fervently for freedom of of conscience, but later in Rome his position on religious liberty may be truly described in the maxim sometimes (perhaps erroneously) ascribed to him, “When error prevails, it is right to invoke liberty of conscience, but when the truth predominates, it is just to use coercion” (ibid., p. 139). For a thousand years thereafter history records the shameful conflict as to which partner, the church or the state, should control the other.

The Welfare State

In earlier parts of this discussion, emphasis was placed on the Christian view that the state was God-ordained to prevent anarchy and preserve social order. More recently Christians have widely insisted that the state, in addition, has the responsibility of extending Christian love to those aspects of public life which affect for good or ill the welfare of one’s neighbors. This may either be approved or condemned as “the welfare state,” according as one is pronouncedly liberal or conservative. Those who supported this view during the 11th to the 15th centuries urged it, not on biblical grounds, but as “an uneasy compromise between the agape of the New Testament and the world powers of feudal society.” Bennett says that it partly tamed this world but at the price of identifying Christianity too closely with the culture of the times and of encouraging too much that was unjust in society. Increasingly in varying degrees, governments have come to regard the principle.

It is proper to introduce at this point the view expressed by the World Council of Churches at Evanston.

Those who make true justice must be made sensitive by love to discover needs where they have been neglected. Justice involves the continuous effort to overcome those economic disadvantages which are a grievous human burden and which are incompatible with equal opportunity to people to develop their capacities. Justice requires the development of political institutions which are humane as they touch the lives of people, which provide protection by law against the arbitrary use of power, and which encourage responsible participation by all citizens. (Evanston Speaks. Reports of the Second Assembly of the World Council of Churches, second section, “Social Problems—The Responsible Society in a World Perspective”)

Translated into particulars, governmental extension of love might cover social security, retirement benefits, assistance to the unemployed, aged and disabled, funds for veterans, housing, public health and care of the sick and mentally ill, soil conservation, agricultural subsidies, restraint of monopolies, regulation of public carriers, free education and the many other benefits.

At the outset of our discussion we conceded that Jesus and his followers prescribed no specific form of government for the state. It must be insisted, however, that democracy seems to be inherent in Christianity. Jesus himself has been called the great democrat. The implications of democracy are unmistakable in the Christian teachings. To the extent to which Christianity prevails in the world democratic government is likely to arise, for it has long been recognized that government tends to assume the pattern of the religion which prevails in a given society. An authoritarian religion produces a government akin to absolutism, and a voluntary religion encourages a government in which freedom is cherished. It becomes increasingly clear that Christianity initiated democracy in the world. Arnold Toynbee declares that democracy is a leaf torn from Christianity, although half emptied of its meaning by being divorced from its Christian context.

We conclude with the assertion that the rule of the people means the recognition of human rights—the right of the ignorant to education, the right of slaves to freedom, the right of the employed to fair wages, the right of the child to be well born, the right of all men to justice. This warrants the establishment of hospitals, schools, orphanages, a free ballot and a free conscience. Under the idea of the worth of man, we have never thought it necessary to claim that all men are equally endowed with gifts, or that they can get equal results; the idea demands only that all men shall be entitled to the same considerations under the law. It asserts that capacity and dignity are not conferred by station or possession but are inherent in the submerged as well as in the fortunately placed. Democracy recognizes that man’s personality is the highest value in the universe and society is to be organized in a manner to minister to his true life. Treatment of man is the test of merit in all institutions, systems, laws, philosophies. “What does it do to man?” is the validating question to ask of any government.

END

We Quote:

HOWARD E. KERSHNER

Author and Editor of “Christian Economics”

The Ten Commandments are the basis of satisfactory economic relationships as well as of morals. Coveting, stealing, untruthfulness, and murder are just as much violations of economic law as of moral law. Such practices in business or government can no more be made right by majority vote than the moral law itself can be changed by that method. One who does not establish a reputation for honesty and truthfulness rarely succeeds in business. The commandment against bearing false witness lies at the very heart of a successful business career. It is a question of morals, to be sure, but equally a question of economics. It is good economics as well as good morals to love one’s neighbor as oneself.—In God, Gold and Government, p. 49 (Prentice-Hall, 1957).

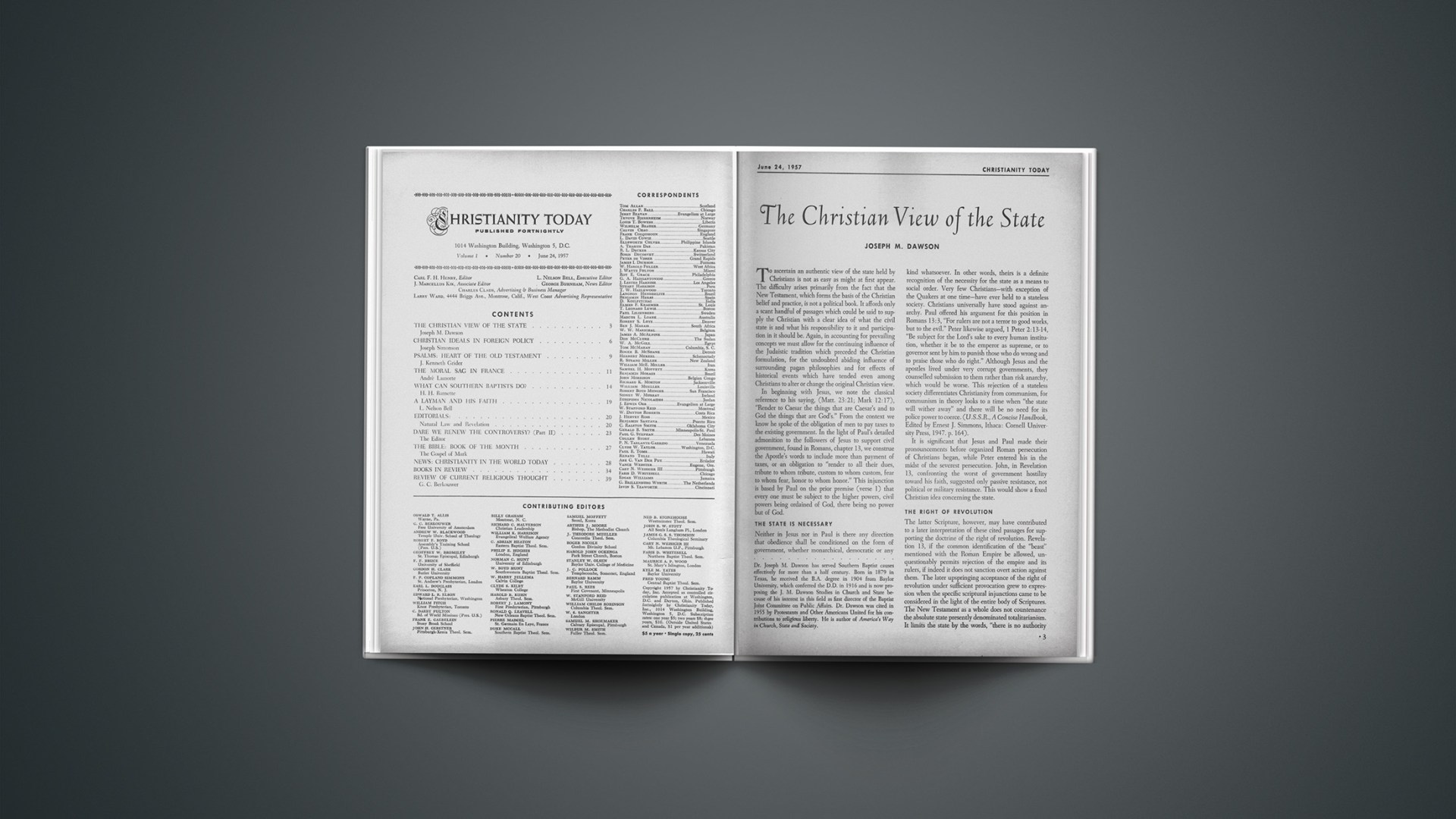

Dr. Joseph M. Dawson has served Southern Baptist causes effectively for more than a half century. Born in 1879 in Texas, he received the B.A. degree in 1904 from Baylor University, which conferred the D.D. in 1916 and is now proposing the J. M. Dawson Studies in Church and State because of his interest in this field as first director of the Baptist Joint Committee on Public Affairs. Dr. Dawson was cited in 1955 by Protestants and Other Americans United for his contributions to religious liberty. He is author of America’s Way in Church, State and Society.