Bogota, the capital of Colombia, is a boom town. Its population, estimated at between three and five million, is growing so rapidly that officials can’t keep count. On a plateau 8,000 feet high in the northern Andes, it is a city of beauty and contrast. Here are the very rich and the very poor. Slum villages of lean-to shacks are squeezed between gleaming skyscrapers and the mountains that rise abruptly east of downtown. Crime, mostly of the purse-snatching variety, is a problem. Panhandlers furtively approach tourists with shiny green objects; they may be contraband emeralds from the nearby mines, they may be soda-bottle glass. Wages are low (Colombia’s per capita income is about $350), and so are some prices. A good steak dinner in a fine restaurant may cost $2.50.

Stretching for miles to the north are new neighborhoods of the middle and upper classes, many of them patroled by heavily armed private guards. To the south are the teeming barrios (suburban districts) of the lower classes. Modern industrial complexes are going up on the western edges of the city, close to the airport and other barrios. During working hours the main streets downtown are choked with crowded Blue Bird buses and ancient American cars. Students abound; there are twenty universities in the city.

Colombia, its 24 million population predominantly Catholic, was the last Latin American country to give legal status to foreign missionaries. Loyalties were fierce; in some areas Protestant services were constantly disrupted, members were harassed, Protestant church buildings were burned. Over the years, however, intense loyalty gave way to indifference, and the Catholic Church experienced spiritual decline. Some of its younger leaders drifted into Marxist causes (the last principal Communist leader was a priest). Many simply dropped out.

But after Vatican II things began to change, interest picked up, and now—with the recent arrival of the Catholic charismatic movement on the scene—a spiritual boom is under way among the Catholics of Colombia. Hundreds of Catholic charismatic groups are meeting throughout Bogota.

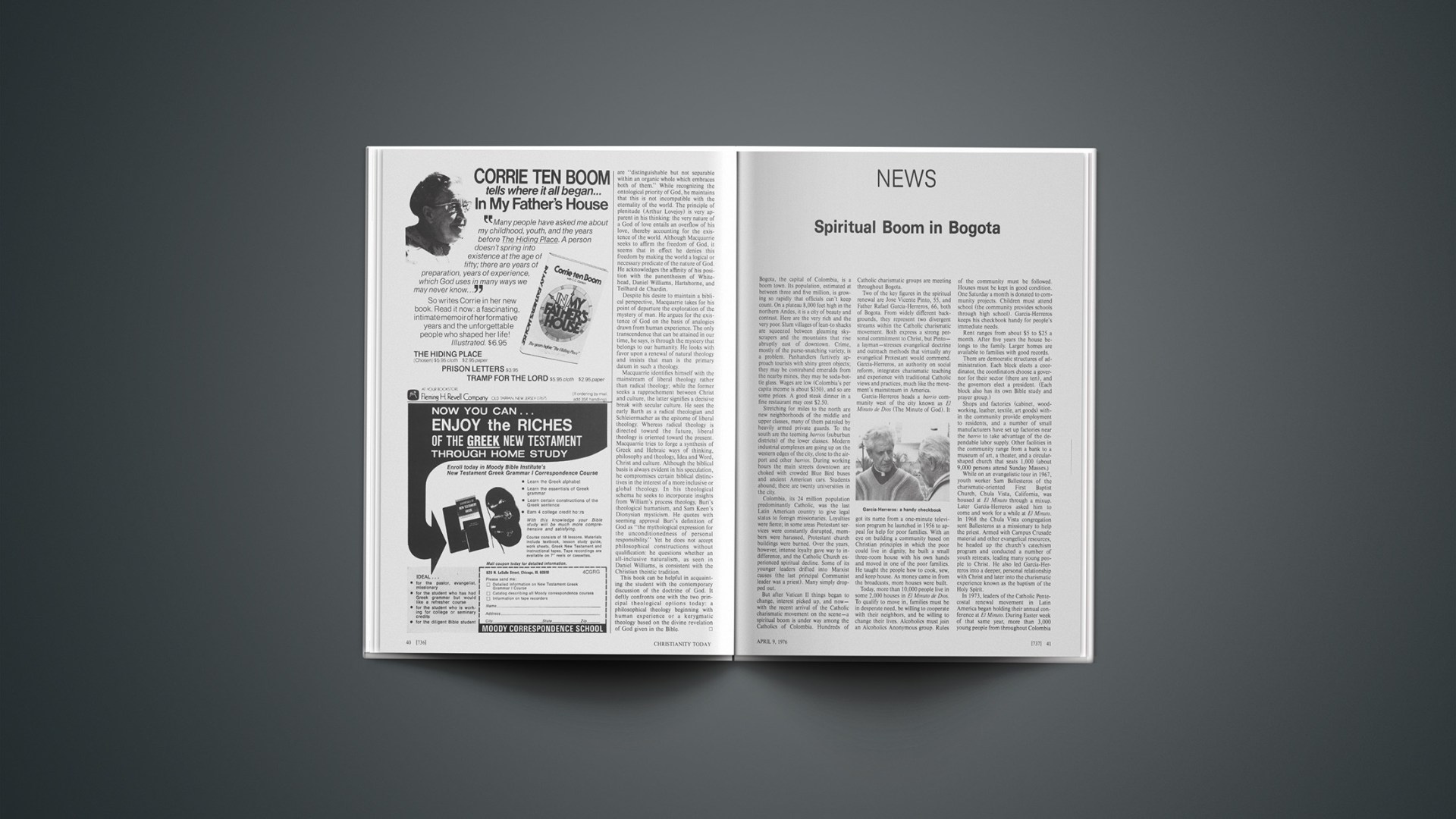

Two of the key figures in the spiritual renewal are Jose Vicente Pinto, 55, and Father Rafael Garcia-Herreros, 66, both of Bogota. From widely different backgrounds, they represent two divergent streams within the Catholic charismatic movement. Both express a strong personal commitment to Christ, but Pinto—a layman—stresses evangelical doctrine and outreach methods that virtually any evangelical Protestant would commend. Garcia-Herreros, an authority on social reform, integrates charismatic teaching and experience with traditional Catholic views and practices, much like the movement’s mainstream in America.

Garcia-Herreros heads a barrio community west of the city known as El Minuto de Dios (The Minute of God). It got its name from a one-minute television program he launched in 1956 to appeal for help for poor families. With an eye on building a community based on Christian principles in which the poor could live in dignity, he built a small three-room house with his own hands and moved in one of the poor families. He taught the people how to cook, sew, and keep house. As money came in from the broadcasts, more houses were built.

Today, more than 10,000 people live in some 2,000 houses in El Minuto de Dios. To qualify to move in, families must be in desperate need, be willing to cooperate with their neighbors, and be willing to change their lives. Alcoholics must join an Alcoholics Anonymous group. Rules of the community must be followed. Houses must be kept in good condition. One Saturday a month is donated to community projects. Children must attend school (the community provides schools through high school). Garcia-Herreros keeps his checkbook handy for people’s immediate needs.

Rent ranges from about $5 to $25 a month. After five years the house belongs to the family. Larger homes are available to families with good records.

There are democratic structures of administration. Each block elects a coordinator, the coordinators choose a governor for their sector (there are ten), and the governors elect a president. (Each block also has its own Bible study and prayer group.)

Shops and factories (cabinet, woodworking, leather, textile, art goods) within the community provide employment to residents, and a number of small manufacturers have set up factories near the barrio to take advantage of the dependable labor supply. Other facilities in the community range from a bank to a museum of art, a theater, and a circular-shaped church that seats 1,000 (about 9,000 persons attend Sunday Masses.)

While on an evangelistic tour in 1967, youth worker Sam Ballesteros of the charismatic-oriented First Baptist Church, Chula Vista, California, was housed at El Minuto through a mixup. Later Garcia-Herreros asked him to come and work for a while at El Minuto. In 1968 the Chula Vista congregation sent Ballesteros as a missionary to help the priest. Armed with Campus Crusade material and other evangelical resources, he headed up the church’s catechism program and conducted a number of youth retreats, leading many young people to Christ. He also led Garcia-Herreros into a deeper, personal relationship with Christ and later into the charismatic experience known as the baptism of the Holy Spirit.

In 1973, leaders of the Catholic Pentecostal renewal movement in Latin America began holding their annual conference at El Minuto. During Easter week of that same year, more than 3,000 young people from throughout Colombia gathered there, and witnesses say a mighty outpouring of the Spirit occurred. Revival spread as the youths returned home.

Each morning and evening priests from the parish teach the Scriptures on radio broadcasts. During vacations, young people of El Minuto travel to outlying towns and villages to witness for Christ. A number of priests have settled in the parish, and some of them teach in nearby colleges and seminaries.

One of the priests, Pedro Drouin, a French Canadian, said in an interview that his encounter with Christ in the charismatic movement had changed not only his life but also his theology. A theology teacher in a Jesuit seminary, he said he formerly spent a lot of time demythologizing the Bible. “Not any more,” said he. “The miracles Jesus performed really happened; the Bible is true,” he declared. He said he now teaches his students accordingly.

Garcia-Herreros and others at El Minuto de Dios have been instrumental in spreading the renewal throughout Catholic circles in Colombia. The priest is well respected in high government and academic circles, and many Catholics and Protestants alike are hoping for a spiritual breakthrough at that level.

Meanwhile, thousands of lives have been influenced by Jose Vicente Pinto. A Jesuit seminary dropout (he had concluded that God had left the church and would have to be sought outside the church), he drifted into social-action causes and eventually into Marxism, discarding his belief in God. As a professor of philosophy and economics in the National University, he wielded much influence upon his students, helping to recruit a number of them for Marxist causes. But not wanting to jeopardize his lucrative government consulting roles, he left the demonstrations and public rhetoric to others.

Plagued by guilt over his hypocrisy, he turned to yoga and drink. His marriage nearly fell apart. In 1973 he reluctantly agreed to attend a charismatic house-group meeting with his wife and other relatives. As a result he began reading the Bible and soon made a profession of faith in Christ. Six months later, he stated, he received the baptism of the spirit. Meanwhile, he had been studying Christian literature and the human scene around him, and he came to the conclusion he should give up his teaching post and work full-time in evangelism and renewal—“on faith.”

“I’ve been totally delivered from Marxism,” explained Pinto, who has been supporting his family on faith for more than a year. “If Christ can solve personal problems, then he can solve humanity’s problems.” And, he implied, the needs were urgent enough to demand his full time. He considered joining Campus Crusade or the Assemblies of God but said he felt God wanted him back in the Catholic Church.

Pinto hosts a number of Bible-study meetings (they often last three hours) both in Cali and Bogota, and hundreds attend. His knowledge of the Scriptures and his ability to communicate them are impressive. He has helped to restore life to the large Our Lady of Carmen Church. A year ago, said the parish priest, attendance at the main mass dropped to about two dozen people. Nearly 1,000 attend now. The services are marked by joyful singing (of mostly evangelical choruses), Scripture reading, and testimonies. The music is led by a “people’s choir” of charismatics.

One of these is Marie Escalante, a harpist with the national orchestra. She and her husband host a meeting of seventy to eighty persons in their home almost every Sunday after the church service. Pinto preaches at the meeting, and each week dozens profess Christ.

The church recently held a two-week training course in discipleship and evangelism. It was conducted by Wedge Alman of Youth With a Mission. (Alman last fall moved YWAM’s Latin American headquarters to Bogota because of the “spiritual openness and response” in Colombia. YWAM has held schools of evangelism in seven Latin countries and trained more than 2,000 South American young people to share their faith.)

Also attending the church is Aicardo Beltran of Campus Crusade. Beltran is part of an experimental ministry Crusade is sponsoring in connection with the Catholic charismatic movement. He oversees thirty prayer groups involving about 1,000 students at eleven universities. He has been with Crusade five years but says that a spiritual breakthrough did not occur among Bogota’s students until two years ago. There has been opposition, he says, “but now even Marxist leaders are coming to Christ.”

Traditionally, Protestant missionaries throughout the world have worked among the poor. Comparatively few have directed their efforts toward students or the middle and upper classes. What is happening in Bogota suggests that this void is at last being filled in the Latin world—by Catholic charismatics who don’t intend to leave their church or their world in the same condition as they found it.

Brazil: A Bright Hope

Evangelical life in Brazil is entering a new era, in the view of observers with international experience. One of the marks of the new day is a publishing venture planned by the Brazilian affiliate of the International Fellowship of Evangelical Students (IFES). The Allianca Biblica Universitaria (ABU) and its equivalent of Inter-Varsity Press began the project by preparing three books for the recent ABU missionary congress.

The congress itself, held at the Federal University of Parana, in Curitiba, has also been cited as a milestone in the development of evangelicalism in Brazil. It was attended by 600 university students and graduates, selected from among 3,000 applicants. Most came from Brazil, but a few attended from other Latin American nations.

An unusual system of selection was publicized in advance. Those who were accepted were required to present their pastor’s recommendation and to complete a correspondence course before the congress. Planners began their work over a year in advance, and the participants they chose came from a wide denominational spectrum.

“Christ Is Lord” was the theme, with “lordship, purpose, and mission” as sub-themes. Of the seven principal speakers who addressed these topics and led Bible studies, four had been participants from Latin America at the 1974 International Congress on World Evangelization in Lausanne.

Improvisation, often considered necessary in South American meetings, was largely absent at Curitiba. Registration was handled efficiently; well-prepared materials were ready for distribution on schedule; cassette tapes of major talks were available within a few hours; and a congress declaration was printed before adjournment.

Missionary opportunities, especially those open to young professionals, were emphasized. Reports came from graduates who had put their professional expertise to work for Christ in Brazil as well as in other countries, particularly those of Portuguese-speaking Africa. One young doctor reported on an evangelical hospital he and a team opened in Brazil’s interior. Afternoon elective seminars showed the need for Christian workers in such fields as agronomy, education, and psychiatry. They revealed the emergence of Christian graduate fellowship groups in several specialized areas.

The week-long Curitiba missions conference, first of its type ever held in Brazil, ended with a service of commitment and communion. Dennis Pape of Ottawa, Canada, former IFES worker in Brazil, was the final speaker. The meeting, as well as other developments he observed on his return to the country, give promise of a new generation of well trained, deeply committed missionaries from the Third World, he said.

Confession In Alexandria

A document confessing various “sins” of African Christians was issued in Cairo by the General Committee of the All Africa Conference of Churches. More than 100 persons from the AACC’s 114 member denominations in thirty-three countries took part in the drafting, according to press reports. Its first public reading was before 2,000 members of the Coptic Church of Egypt at a meeting in St. Mark’s Church in Alexandria.

Entitled “The Alexandria Confession,” the statement says that African Christians have sinned in “speaking against evil when convenient, siding with oppressive forces in their own societies, condemning evils done by foreigners and condoning the same evils by our own people, turning a blind eye to injustice in our societies; in short, being a stumbling block for many.” It calls for a more comprehensive understanding of liberation in the face of what it calls “enslaving forces and abuse of human rights in independent Africa.”

In business sessions, the AACC committee called for an end to apartheid in South Africa, backed the Palestinians on the issue of “national rights,” and urged the people of newly independent Mozambique and Angola to unite “to advance the frontiers of national liberation, justice, and freedom as far as the Cape of Good Hope.”

A Moratorium On Moratorium

The call for a moratorium on foreign mission personnel and funds is still “too vague, irrelevant, and empty of content and context,” commented General Secretary John Kamau of the National Christian Council of Kenya at a recent meeting in Arusha, Tanzania, of heads of church councils in eastern Africa. (Kamau’s Kenya council was the principal host for the General Assembly of the World Council of Churches in Nairobi last fall.)

Until the Arusha meeting, Kamau had remained silent in the five-year-old debate on moratorium, a proposal aimed at preserving cultural identity and giving national churches time to develop their own resources and priorities. It had been assumed that Kamau had supported his close friend and fellow Kenyan, General Secretary John Gatu of the Presbyterian Church of East Africa. Gatu, a main spokesman for the moratorium concept, is also chairman of the All Africa Conference of Churches (AACC), which issued an official call for moratorium at a meeting in Lusaka, Zambia, in 1974 (see June 21, 1974, issue, page 35). He was also a participant in the 1974 Lausanne Congress on World Evangelization.

Kamau, however, sternly criticized Gatu, AACC general secretary Burgess Carr, and Kofi Appiah-Kubi, the AACC’s secretary for theology. The debate led by these men, he said, “has no positive goal.… What the church in Africa wants is development towards self-reliance.” He went on to dispute Appiah-Kubi’s contention that moratorium is working well in many areas of secular life in Africa.

Kamau argued that the emphasis should be not on whether money and personnel are sent but on how these resources are being used in the development of the churches. “It is freedom in the decision-making processes that is vital,” asserted Kamau. “There should be no hidden pressure whatever regarding acceptance and use of funds and personnel, and programs ought to be designed and managed locally.”

Evangelism and relief work ought to be regarded as urgent operations for the churches of Africa, he said. And “such opportunities for service should not be clouded up or bypassed while we engage in vague and confusing debates.”

In the end, Kamau carried the day. The leadership gathering adopted a statement calling for measures to enable east African churches become self-reliant as soon as possible, and for development of mature patterns of relationship between the churches and Christian aid agencies in Europe and North America. In effect, it called for a moratorium on moratorium.

ODHIAMBO OKITE

Search For Meaning

The Salvation Army, a founding member of the World Council of Churches, has apparently decided to live with a recently approved amendment to the WCC’s constitution rather than contest it any further. The amendment, passed at the WCC’s general assembly in Nairobi in December, calls member churches “to the goal of visible unity in one faith and in one eucharistic fellowship expressed in worship and in common life in Christ, and to advance towards that unity in order that the world may believe.”

Prior to the assembly, Salvation Army commissioner Harry Williams discussed the proposed wording with other Army officials and with representatives of the Society of Friends (Quakers). Because the groups do not celebrate the Eucharist (communion), they cannot be called “eucharistic” fellowships. Williams, a member of the WCC’s executive committee, then raised the issue on the floor of the assembly. A strict interpretation of the amendment would exclude the Army, he argued.

WCC general secretary Philip Potter replied that there was no wish to exclude the Army or any other non-sacramental group, and that such an implication should not be read into the statement.

The amendment carried, but “it was made clear by many delegates that there was widespread sympathy for our position,” Williams told correspondent Roger Day. “Perhaps the reaction was most beautifully expressed by a Swiss theologian who said, ‘We all regard the total life of the Salvation Army as sacramental.’ ”

For now, Army leaders seem intent on avoiding hassles over the statement’s phraseology. Critics of the WCC, though, view the situation as just one more reason for asking, Does the World Council of Churches really mean what it says when it speaks?

Saint In Waiting

John Fagan was 52, weighed seventy pounds, and was dying of stomach cancer. He had not eaten for seven weeks, and his wife had been told by their doctor that he would not last the weekend. It was Saturday, March 4, 1967. On Monday morning Fagan startled his wife by asking for a boiled egg. When the doctor arrived he was “visibly shaken” on seeing his patient.

John Fagan is now 61, weighs 120 pounds, and shows “no clinical or radiological evidence of residual disease.” His story was revealed at a press conference last month in Glasgow, Scotland. His cure has been hailed as a miracle in the Catholic Church, and it may give Scotland its first “saint” since Queen Margaret was canonized in 1250.

The medical facts, both before and after, are not in dispute. The family doctor was astonished by Fagan’s recovery but ruled out the possibility of a miracle. He was not, he said, a religious man. Other non-religious medical specialists admit to being baffled, and refer somewhat imprecisely to a cancer phenomenon known as “spontaneous regression” or “natural remission.”

The Fagans have a different explanation. During what seemed to be the terminal stage in 1967, a local priest gave Mrs. Fagan a medal of Blessed John Ogilvie. The only post-Reformation Catholic to suffer martyrdom in Scotland (1615), Ogilvie is also the only one to have been beatified (1929).

Mrs. Fagan pinned the medal on her husband’s clothing and began praying for Ogilvie’s intercession. The cure took place a few weeks later. Fagan says that the experience has humbled him and that his faith, formerly “wishy-washy,” is “much stronger now.”

Meanwhile the process toward Ogilvie’s canonization has continued with a thorough investigation into the case. The “devil’s advocate” did his traditional best to disprove the supernatural explanation, but admitted defeat.

The Vatican has now decided that a miracle did indeed take place, and it seems probable that Ogilvie will be raised to sainthood toward the end of the year.

Said Dr. Thomas Winning, archbishop of Glasgow: “We are not asking the public to believe that a miracle took place. We only state the facts of the case and leave them to decide for themselves.”

J. D. DOUGLAS

DISORDERLY CONDUCT

A congregation of the Church of God in Christ in Wichita, Kansas, has asked a court to stop four of its members from disrupting services. Bishop Graze Kinard says the four have run through the sanctuary moaning and shouting while he tried to conduct services. He alleges that they shut the pastor’s Bible while he was preaching, took away the pastor’s microphone and hit him over the head, and pinned down the pianist’s arms. Police have had to step in several times, and the congregation has dwindled from 600 to fifty because of the trouble, complains the bishop. The trouble apparently stems from a battle over control of the church, say police.

Stop The Ceremony

A call to end “this wedding hypocrisy” was made recently by a Church of Scotland minister who suggests that since the church cannot prevent people being divorced by the state it can at least stop them marrying in church. In Life and Work, the official publication of the Kirk, minister James Miller of Peterhead Old Parish church said that if the church continues to conduct marriage services it ought also to be the authority to divorce those married by it. If not, then both marrying and divorcing should be done by the state.

Miller declined to go into what he called the “notoriously ambiguous” Gospel testimony about divorce. What troubles him is the “ecclesiastical self-delusion” whereby “those whom God joins together are not infrequently put asunder by the state, without so much as a theological quiver.”

Introduced as an expression of personal opinion, his brief article hit the national headlines at a time when parliament is discussing bringing Scottish divorce laws into line with those that apply to England and Wales. If legislation is passed it would mean that in Scotland also the only ground for divorce would be expressed by the comprehensive description “the irretrievable breakdown of marriage.”

J. D. DOUGLAS