A director of administration at a seminary told a story of a student who rode into school on a motorcycle, carrying all his worldly possessions in a worn-out pack, and wearing long, unkempt hair. After about a week the student announced that he was leaving, explaining that “There is no support community for me here.” “I couldn’t help laughing,” said the administrator. “A few years ago a number of students left for the same reason; but they were clean-shaven and had short hair!”

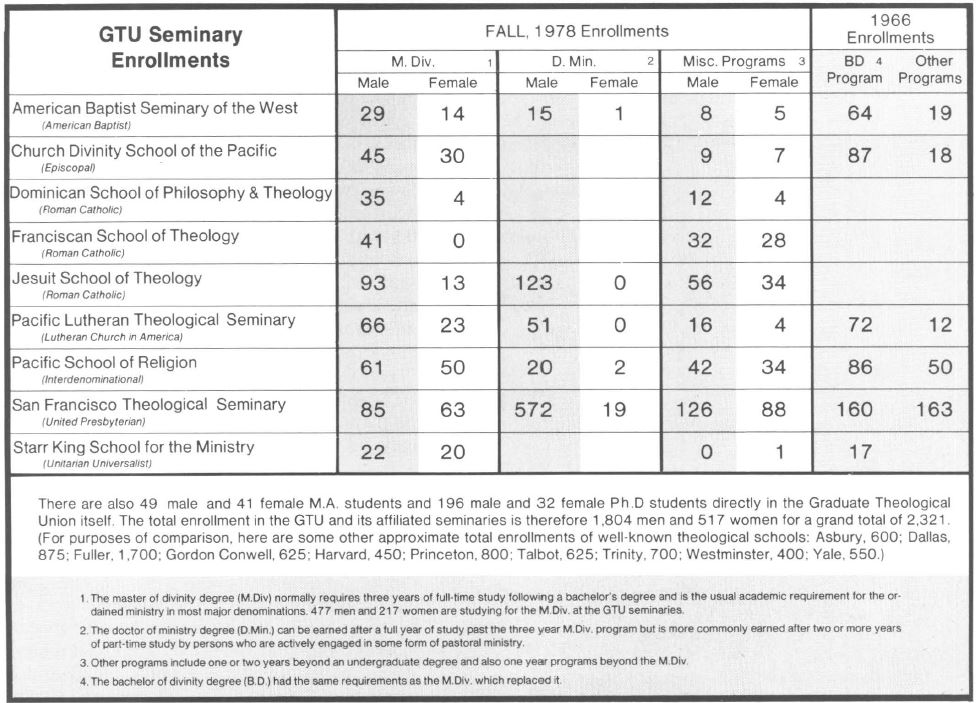

Students who attend nonevangelical seminaries are changing. That fact should not get lost amid all the media attention lately given to evangelicals. For example, consider the Graduate Theological Union (GTU) in Berkeley, California, across the bay from San Francisco. The GTU has two degree tracks. It offers in its own name M.A. and Ph.D. programs in several theological fields, in cooperation with the adjacent University of California. It is also a consortium of nine Bay Area seminaries, most of which are based in Berkeley, and each of which offers a variety of degrees relating to professional religious ministry.

The most visible change in the student body is the number of women. Although the total number of divinity students in the GTU has increased by less than 10 per cent since 1968, the number of women has increased from a mere 5.5 per cent of total enrollment a decade ago to more than 30 per cent today. In four of the six non-Catholic seminaries, women now account for 40 per cent or more of the Master of Divinity (M.Div.) students. Given the present trend, reference to women seminarians as “minority” students, at least at the GTU, may soon be an anachronism.

Although not quite as visible as the influx of women, the most pervasive change among GTU students is probably their attitude toward authority. “A few years ago,” remarked a professor at a GTU school, “it was chic to deny any kind of authority.” Using even sharper words, an administrator at another school likened the seminary students of the sixties to “howling children” who required a burdensome amount of administrative time. They disliked Roberts’ Rules of Order, but they consumed more time debating the methodology for deciding an issue than discussing the issue itself. Faculty members and administrators agree that today the atmosphere is completely different. The demand of students five or ten years ago for participation has been largely replaced by a willingness to be directed.

This new respect for authority is not limited to administration, but extends to academics as well. An index of this change is cross-registration. The school that receives the greatest number of outside students is the Jesuit School of Theology, where courses are more rigorous, and where the lecture is viewed as an art form. Students express a desire for academic guidance on a structural level, as well. A few years ago, M.Div. students in the GTU seminaries could design their own academic programs. On the first day of class they would “contract” with their professors for the substance of the course. Such requirements as term papers and tests were venomously scorned, where not already proscribed. But no longer. Most of the GTU seminaries now have rigid core curricula for the first year of their M.Div. programs, only gradually increasing the number of electives over the next two years. Inside the classroom, professors report that students are increasingly serious about their studies: They want substantive coursework, good syllabuses, and thorough bibliographies. And most schools—with the ready endorsement of students—have replaced the pass/fail system, which became standard a decade ago, with grades. As with university students around the country, seminarians at the GTU want to receive the skills and knowledge needed for their future careers.

The interest in spiritual matters no doubt varies from student to student. But there is little doubt that an interest in spirituality and mysticism has replaced our earlier preoccupation with political activism.

Students also show a dramatically renewed appreciation of authority in the area of history—particularly the history of their own theological traditions. This is especially clear in the study of liturgies. Browne Barr, dean of the faculty at San Francisco Theological Seminary, puts it this way: “I think you could do a social history of contemporary students by charting the arrangement of church furniture. There was a time when they thought we could save everybody by flexing the pews and playing the guitar.” Although some schools still experiment, they are no longer the rule. Says Barr: “The lightness with which the students either dispensed with or rearranged the liturgy a few years ago is now seen as an act of arrogance.”

Students also seem to be investigating, if not actually endorsing, biblical authority. Last August and September a surprising ninety-five students took intensive Greek and Hebrew courses at San Francisco Theological Seminary—despite the fact that not one GTU seminary requires its M.Div. students to study biblical languages. Some denominations still require them; but that does not explain, as Barr reports, why language study is now regarded as “a great adventure, not a chore.” Other students are finding the study of the English Bible to be a great adventure. During each of the past four years at Berkeley’s Pacific School of Religion (Interdenominational), more than thirty students have arrived three weeks before the fall term in order to read through the entire Bible. And at the American Baptist Seminary of the West, one of the largest GTU courses offered this year is “The Bethel Series.” Well-known to local churches throughout the nation, this two-year Bible study program is being offered, experimentally, to seminary students.

No one can do more than speculate why all of this has happened, but there does seem to be a consensus. First, the Viet Nam War. As well as inspiring a mood of protest, U.S. participation in the Viet Nam War brought into the seminaries many students who only wanted to evade the draft. At a GTU school, about one-fourth of the student body left when the lottery was introduced. Second, age. Students now attending the GTU schools are older than students of a few years ago.

This, too, relates to the exodus of draft-evaders. Also, more students are attending seminary after a “religious experience” of some sort. And many of them have changed careers to do so. Third, the wave of conservatism sweeping the country. Seminary education, as with secular education, seems to be undergoing a back to the basics movement. As a student put it: “Maybe around here you can do far-out stuff, and that’s acceptable, but for people in the congregations, it’s a different thing. You can’t get too far away from the basics.” Students today understand this before they leave seminary.

After the change of attitude toward authority, the most striking difference between GTU seminary students today versus five or ten years ago is in the area of spirituality. The interest in spiritual matters no doubt varies from student to student. But there is little doubt that an interest in spirituality and mysticism has replaced an earlier preoccupation with political activism.

Students a few years ago took such courses as “Social Change in White Churches”—an undisguised attempt to transform local congregations in the Bay Area into political advocacy groups. The students did not simply study church-and-state relations, but “Church, State, and the Right to Revolution”; not simply art, but “War and Peace and Politics in Art”; and not simply poetry, but “The Poetry of Protest.” This has changed. The Center for Urban Black Studies, which used to attract scores of students to its courses—particularly to “The Pastor as Revolutionary”—has nearly withered in the dry heat of indifference. The center canceled one of its two classes scheduled for this fall: lack of interest. The other has four students enrolled. Outside the classroom political activism is conspicuously absent, even within the powerful women’s block. The Center for Women and Religion is weaker, and remonstrances against every use of “sexist language” no longer seem to be a categorical imperative.

I don’t want to suggest that GTU seminarians have abandoned their interest in the relationship between religion and society. The Center for Ethics and Social Policy is thriving, and forums on social thought and social concern are numerous. But students study the relationships between religion and society. They ask questions, rather than assume answers.

“Spirituality is the thing now,” states GTU Registrar Elizabeth Over. The largest classes today are likely to have such titles as “Studies in Spirituality: 1570–1870,” “Spirituality and Social Justice,” and “The Varieties of Spiritual Experience.” Between January and June of 1978 there were no less than thirty events having to do with spirituality—mostly eastern. Not atypical was the program entitled “Mantra, Meditation, and Prayer,” with Sant Keshevadas; and at the Pacific School of Religion there was a series last year on “Yoga and Movement,” followed by formal meditation—for Vespers. Students were so interested in eastern religions that three adjunct professors were brought into the GTU last year to help teach them. But reports indicate that fascination with the human potential movement and eastern religion is waning. At the same time, Christian spirituality appears to be in the ascendant. Chapel attendance at the various seminaries has increased dramatically. There are reports of spontaneous prayer groups here and there. And the Shalom Prayer Group, a charismatic fellowship of mostly GTU students, attracts as many as seventy-five people to its weekly meetings at the Jesuit seminary.

Observers can only surmise why students have a renewed interest in spirituality. L. Doward McBain, president of the American Baptist Seminary of the West, pinpointed the most important reason: “The dangerous world in which we live, in which great powers can vaporize most of civilization, has had its effect on theology. We’re not permanent in this world.” McBain also points to an internal factor: the increased vitality of the church itself, particularly with the evangelical awakening. Browne Barr concurs. Although he admits that the GTU seminaries have not grown larger from the groundswell of evangelicalism, he believes that “a sense of the transcendent” has been brought into the GTU seminaries by way of evangelicalism “in a new and refreshing way.” Evangelicalism, combined with the emphasis on meditation in eastern religion, helps explain, says Barr, why “prayer is no longer a naughty word.”

Now when students study the relationship between religion and society they ask questions rather than assume answers.

Where is this new breed of seminary students headed? Here we hit upon another major change: the reawakening of the parish ministry. James Jones, professor and director of field education at the Church Divinity School of the Pacific (Protestant Episcopal), noted that just five years ago it was hard to persuade students to take field work in local parishes. “They wanted something more exotic.” Now he has trouble keeping them out of the parish. Every faculty member and administrator interviewed agreed that the local parish has regained a position of respectability among seminary students. The realities of the job market may have something to do with this shift, but that does not entirely explain it. Jones points out that while only one-third of the seminary students in 1972 intended to become pastors, the vast majority actually did so when it came time to find a position. The difference between then and now is that “today’s students enter and leave with the idea of going into the parish ministry.”

Paul F. Scotchmer is a freelance writer in Berkley, California.

————————-

Three Other Seminaries In The Bay Area

The nine GTU seminaries represent most major American denominational traditions, especially when you realize that the Pacific School of Religion has many Methodists attending and historically has Congregational ties. There are also three major non-GTU seminaries. Therefore, the Bay Area, along with Chicago, is one of the two most representative centers of theological education in the country.

San Francisco Baptist Theological Seminary was founded in 1958 and uses facilities provided by Hamilton Square Baptist Church in downtown San Francisco. It was originally part of the Conservative Baptist movement, but that tie was broken several years ago. It is not now linked to any Baptist denomination. The school has no women students; sixteen men are studying for the M.Div. and four more for the Th.M. It stands “solidly in the position of Fundamental separatism, defending the dispensational premillennial interpretation of the Word of God.” As such it is more or less similar to about a dozen graduate schools scattered across the country, mostly young and baptistic, that have emerged to train ministers (along with the older undergraduate Bible colleges) for the fundamentalist wing of evangelicalism.

Golden Gate Baptist Theological Seminary is the western-most of six Southern Baptist Convention-owned schools and is located in Mill Valley, a dozen miles north of San Francisco. It was founded in 1944, symbolizing the westward expansion of the largest Protestant body in the country. In the fall of 1977 it enrolled 474 students in its various programs, over 200 more than it did a decade earlier. Only about 6 per cent of the M.Div. students are women. Neither Golden Gate, nor any of the GTU seminaries, are any match in size for the four Southern Baptist seminaries in the heartland of the denomination: In the fall of 1977 they enrolled more than 7,700 students.

Saint Patricks’ Seminary is in Menlo Park, thirty miles south of San Francisco, and serves about eighty-five students preparing to become Roman Catholic diocesan priests. Such priests normally engage in pastoral careers. There are about fifty such seminaries and their nationwide enrollment in 1977 was a little over 3,000, about 60 per cent of the level of a decade ago. There are another fifty or so seminaries closely identified with religious orders, including the three in the GTU. Nationwide, there are about 2,000 students in them. Priests in religious orders are more likely to engage in academic, missionary, or other specialized ministries. (When much larger figures for Catholic seminarians are reported they include boys in the high school and college level stages of preparation for the priesthood.)

Absent from among the Bay Area seminaries is a strong multi-denominational evangelical institution such as Asbury, Dallas, Fuller, Gordon-Conwell, Trinity, or Westminster. A small start at partially filling this void is to be made this September when regular operations commence for the New College for Advanced Christian Studies adjoining the GTU. New College, however, does not intend to offer an M.Div. (See news story, Oct. 6, 1978, p. 50.) Saint Joseph of Arimathea Anglican Theological College is also being launched in Berkeley to provide priests for Anglo-Catholics.